Most football fans will remember Alastair Lynch’s leading role in Brisbane Lions’ premiership dynasty. But before then, he lived an AFL career which was almost ended by a mystery illness then almost derailed by a drugs charge. He opens up on the SACKED podcast.

Alastair Lynch was prepared to accept any diagnosis — even cancer — if it meant he could finally unlock the cause of the debilitating illness which threatened his AFL career early in his time with Brisbane.

Lynch had been portrayed as the great white hope for the bad news Brisbane Bears when he almost reluctantly left Fitzroy with an offer too good to refuse at the end of 1993 to take up the game’s first 10-year contract.

But just a season and a bit into his time with the Bears — who would later merge with his former side Fitzroy — Lynch was bedridden, sapped of energy and fighting an illness that he didn’t have a name for, leaving some of his new teammates privately questioning him.

“I almost don’t know how I got to the finish line of that first season (in 1994, due to a series of injuries)…(but then) something broke and I was cooked,” Lynch told the Sacked podcast.

“I went from being a super fit 27-year-old who could do whatever he wanted — whether it was training hard or playing hard — to being bedridden and sleeping 12 to 15 hours a day, and waking up more tired than when I went to bed.

“I was in that mental state where I was going to have all the tests done, hoping that I had a positive test. ‘You tell me what it is, and let’s start the treatment’.

“Like all of our families, we have been impacted by horrible diseases and that sort of stuff.

I was getting brain scans, I was hoping I had cancer. It’s ridiculous (looking back on it), but that was the state of mind, because I wanted something to fight.

HE’S ‘TAKING THE PISS’

Almost two decades on, Lynch understands that some must find it strange that he was actively seeking a positive test so he could take up the fight to whatever it was ailing him.

But he desperately needed answers.

And making it even tougher, he heard the whispers inside the club that some thought he was taking “the piss” by not playing.

He played only one game in 1995 as he wrestled with the mystery ailment.

“There were no real answers,” he said.

“Whatever this physical disorder was that I had — which no one seemed to really know — (was) being compounded by a mental challenge, because I did not know what was going wrong.

“There were comments around the club … understandably there were frustrated people. I had a 10-year contract, whether I played or not, so there was speculation around …‘Is he pulling the piss with this stuff’.

“I couldn’t expect (others to understand) because I had no idea what was wrong with me.”

Finally, a consultation with ear, nose and throat specialist Dr Jack Kennedy — a Collingwood board member — revealed he had “post viral syndrome”, a form of chronic fatigue syndrome.

“I thought ‘beauty, I’ve got a name, let’s go and get chronic fatigue treatment’. Be buggered, there was no real treatment. People didn’t understand chronic fatigue (back then),” he said.

One specialist even cold-heartedly told him he didn’t believe in chronic fatigue syndrome.

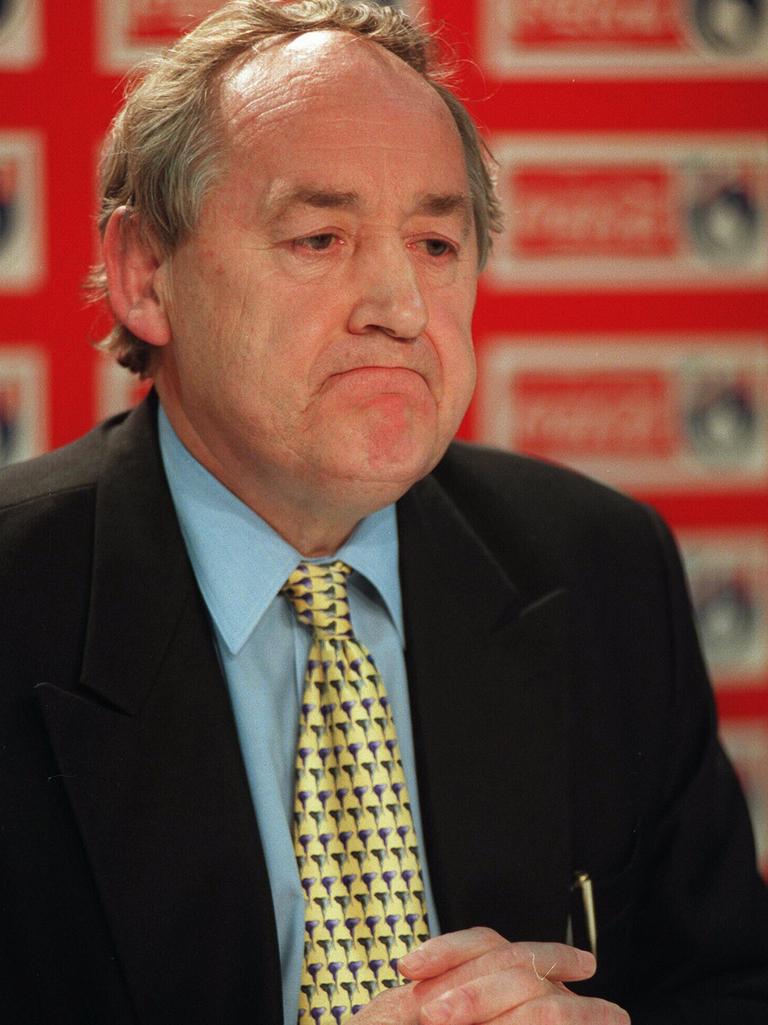

Lynch promo 1

CHARGED AND ACQUITTED

Lynch returned to the field for the Lions in 1996, playing 18 games, then 20 more the following season.

But just when he felt as if he was getting his life, and his footy career, back from the brink, he faced a challenge almost as difficult in 1998.

“I had very low testosterone levels and the precursor to that was that (a chronic fatigue specialist in Brisbane) prescribed hormone DHEA,” Lynch said.

“I was taking a herbal extract to help promote that hormone and I went to pick up my medication at the pharmacy one day and the guy I normally picked it up from said ‘this has just been listed on the banned list’.

“So I spoke to the club straight away and I rang the (ASADA) hotline. I spoke to the guy and he told me yes it was (now) on the banned list but to ring the AFL and put in an application to take it as part of your medical treatment.

“I sat down with (then AFL footy boss) Ian Collins one afternoon at the Gabba and went through exactly what I’d been doing … and put in the application.

I asked them at the time, ‘Do I keep taking the medication?’ They said, ‘Absolutely, keep taking it’. I got tested twice over the next period and tested negative both times because I was taking this minuscule amount to just bring me into the bottom end of the normal scale.

Then came the shock.

Lynch received a letter informing him that he had been charged under the anti-doping code of the AFL.

“It was staggering … and traumatic,” Lynch said.

He will never forget the support he received one day at Waverley from an unlikely source — the St Kilda cheer squad — which warmed his heart, as well as the strong backing he had from the Brisbane Lions and the man who represented him, lawyer David Galbally.

He was cleared … and allowed to play on.

Lynch promo 2

THE HUDDO FACTOR

Lynch had left school halfway through Year 11 to start work on the King River scheme in Tasmania.

He was working in Queenstown when signed for Lyell Gormanston Football Club in the rough and tumble west of Tasmania.

But he was ‘sacked’ before he even played a game.

“I signed a contract with Lyell Gormanston, and I reckon before the season had started, a couple of weeks into training, the coach actually said to me: ‘Look, we recommend it’s best for you to go back to (play with) Wynyard (under 19s),” Lynch recalled.

“I think he identified that I was petrified.”

Were you sacked?

He laughed: “He thought it was best for my development (to play elsewhere), and I felt it was best for my life.”

Lynch’s dad called on an old mate to set him on a football pathway that would one day lead him into the AFL.

“Dad rang one of his great mates who he played state junior football with, Peter Hudson,” Lynch said.

“Huddo had just taken a job with the Hobart Footy Club.

“My dad was five foot 10 and he rang Huddo and said: ‘My son is 16 and he wants to come down to Hobart’. Huddo was thinking (Lynch would be) a nuggety little five foot 10.

He reckons his ears pricked up when he said: ‘He’s six foot four and he runs OK’.

It turned out to be a pivotal moment.

“I’m so fortunate that I had this investment from a guy like Peter Hudson.

“After training I’d either have Huddo or one of the trainers just kick the ball at me. I had to make it 100 times in a row before I went in.

“Kevin Sheedy sent Paul Salmon over to train with Huddo one night … and Huddo got Royce Hart to come down to training and do some marking with me.

“I was 17, I wasn’t a massive footy head, but I knew who Peter Hudson and Royce Hart were.”

Hawthorn and Collingwood were interested, but it was Fitzroy who chose him at pick 50 in the 1986 national draft.

“I remember I got a phone call late on the night of the draft from (Lions secretary) Arthur Wilson at Fitzroy, saying: ‘We picked you at 50’,” Lynch recalled.

“There was nothing on the radio and certainly nothing on TV. I can’t remember whether I even nominated for the draft. I was just plucked out.”

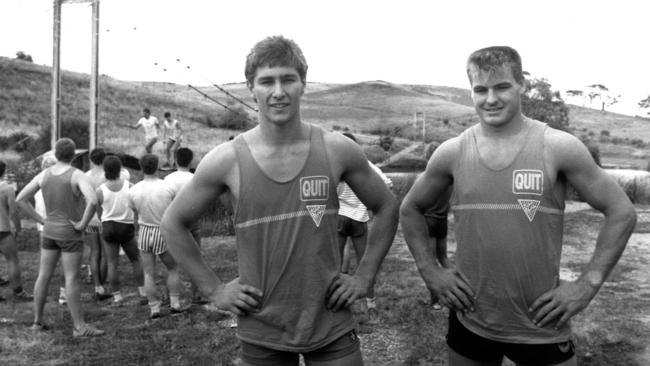

Lynch sacked 3

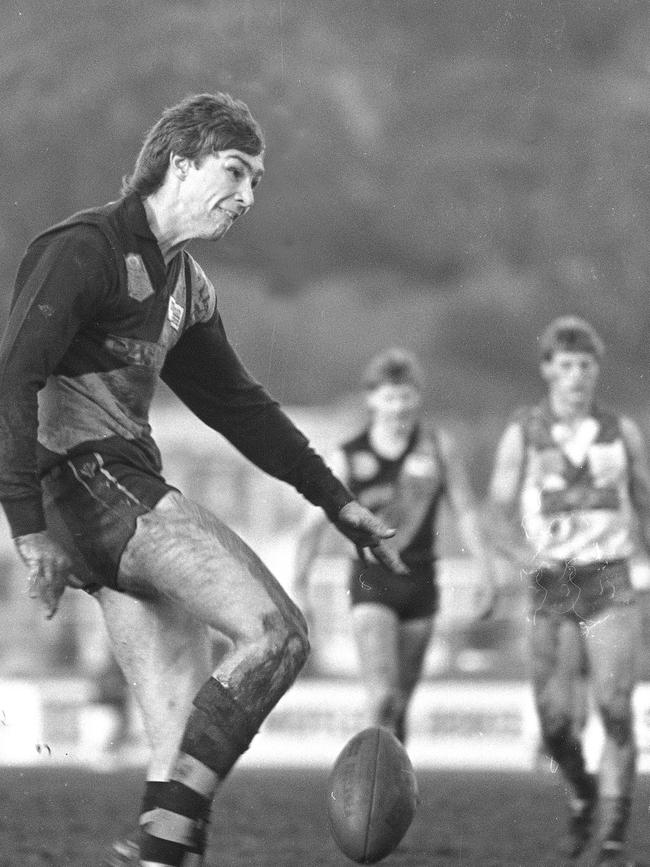

DROP KICKS, MARK OF THE YEAR AND PLUGGER

Lynch kicked 633 goals across his brilliant 306-game AFL career, but his first major put him into rare company in the modern era.

Of all things, it came from a drop kick.

In his debut game for Fitzroy against Footscray at the Whitten Oval, in round 3, 1988, Lynch came off the bench midway through the first term.

“Leon Harris grabbed the ball … and I’ve come screaming past. I think he obliged me and handballed the ball to me,” he said.

“I just drop-kicked a little dart and it became a bit of a habit over the next three or four years. If I was anywhere near the goalsquare, I was kicking drop kicks, even if I wouldn’t recommend it now.”

By day, he was, “the worst bank teller” at the National Australia Bank in St Kilda Rd, and by weekends he was one of the Lions’ brightest stars.

One of his biggest individual challenges came in his 21st game, in 1989, when Fitzroy took on St Kilda at Waverley.

He had kicked his third goal and when the runner came to him, he expected “a pat on the back”, not a demand to come off the ground.

“He (the runner) said: ‘You’re off’. I thought: ‘What? I am going OK for once’. He said: ‘The coach wants to talk to you’ and I thought I wouldn’t mind speaking to him actually.

“I’ve grabbed the phone. I can’t remember whether I spoke to (coach) Rod Austin or Robert Shaw as the reserves coach.

They said: ‘We’re getting Perty (Gary Pert) off, you’re going to full back on ‘Plugger’ (Tony Lockett”. I am thinking ‘Perty is the best full back in the game, he’s the Victorian full back and ‘Plugger’ is at the peak of his powers’. I felt violently ill.

“He (Lockett) wasn’t overly enamoured with humans at that time. He genuinely wanted to hurt people. I was thinking ‘I’ve just got to survive this game’. So I adopted the tactic of playing him from about three metres behind. I was fairly quick and Plugger was quick as well, but I thought I’m better off surviving and living to tell a story.”

That same year Lynch took the mark of the year against North Melbourne, which won him a new Holden Jackeroo.

The memory lasted forever; the car didn’t.

Four years later the Herald Sun’s then police reporter Scott Gullan told readers that Lynch’s car had been stolen from outside the Fitzroy Club Hotel after a Lions’ match, and was found torched.

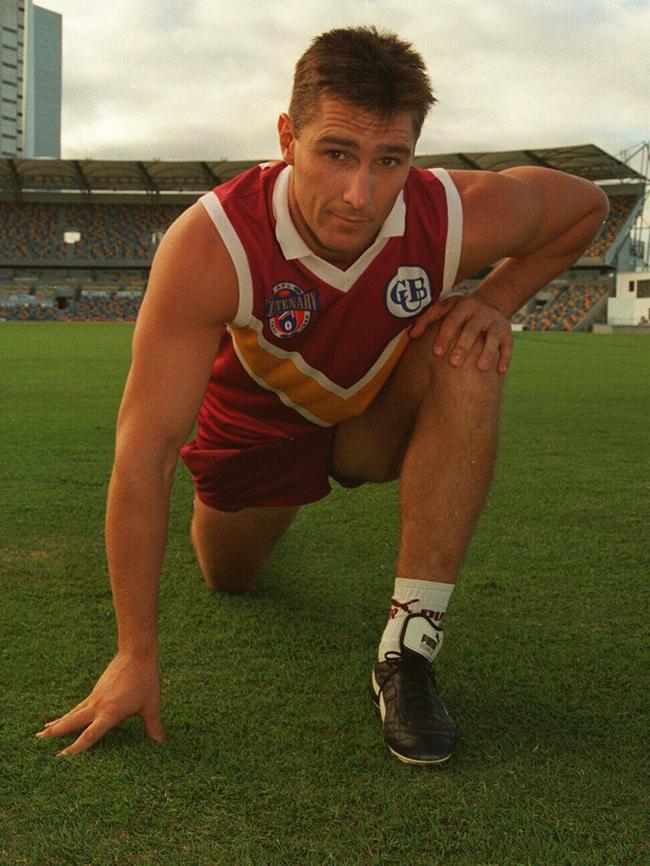

‘WE’LL GIVE YOU A 10-YEAR CONTRACT WHETHER YOU PLAY OR NOT’

Lynch was Fitzroy’s best player in 1993, winning the club’s best and fairest and kicking 68 goals from his 20 games.

He loved the Lions.

But a bold play from Brisbane — and his former Fitzroy teammate, Scott Clayton, who was working with the Bears — presented him with the chance of a free game of golf and a trip to Queensland to look at their facilities.

Still, he had no intention of leaving Fitzroy — despite its financial woes — until the Bears gave him an opportunity he couldn’t refuse.

“They put the proposal for the contract to me, and I thought ‘Geez, I didn’t expect that’,” he said.

“I remember it was this ridiculous amount of money.

“My reflex (response) was, ‘I need directors’ guarantees’. They said: ‘Yeah no worries’.

“I said: ‘I need a long-term deal’. They basically said: ‘We’ll give you a 10-year contract’. I am sure I laughed. I was 26 at the time and I said, ‘I won’t play for 10 (more) years’.

“And that’s where the punchline was, ‘You misunderstand what we are saying … we’ll give you a 10-year contract, whether you play or not’.

That sort of took my breath away. I never considered leaving Fitzroy (until then).

Lynch revealed to Sacked that his playing contract totalled $1.8 million, with a job at Coca-Cola worth another $35,000 a year.

He had no choice but to take the offer, even if he felt he had let Fitzroy down.

“It (my conscience) wasn’t clear because I felt I had let down a lot of Fitzroy people.”

He even attended a meeting of the ‘Lynch Mob’, a group of Fitzroy fans named after him, at the Fitzroy Club Hotel, after announcing he was leaving.

“It (the group) started as a loyal bunch of mates who would come along with their ‘Lynch Mob’ sign and they had been so supportive of me,” he said.

“I don’t know if it was a good thing or not (to attend), as there were supporters there who were pretty pissed off with me. That’s fair, and understandable.

“I asked to speak to the group … I got on stage and couldn’t get a word out. It was a very emotional time. I went back up there and didn’t try to ask for forgiveness or anything like that. I said, ‘This is the reason why (I am doing it)’.

“I don’t know how well I did it, but I am glad that I did.”

TRIPLE FLAGS

Lynch doubted he would complete the 10 seasons of his Brisbane contract when he signed on the dotted line.

And it looked highly unlikely when he battled his debilitating chronic fatigue syndrome.

But he made it — easily.

And by hanging around he became a critical member of one of the greatest sides in VFL-AFL history — the triple premiership-winning Brisbane Lions.

The arrival of Leigh Matthews, and the maturation of what turned out to be a super team, saw the Lions win a hat-trick of flags from 2001-2003 before just falling short of making it a fourth in the 2004 grand final.

Lynch feared for a moment he might miss his chance in the first year of that three-peat, having been suspended for striking Darryl Wakelin.

“I got a one-week suspension, it could have easily been two,” he recalled.

A two-week ban would have seen him miss the 2001 grand final, but thankfully his one-week ban saw him sidelined only for a preliminary final.

He returned for the grand final against Essendon — the team that Matthews had forged an ‘if it bleeds, you can kill it’ mantra earlier in the season — and fittingly after all he had been through, Lynch held the Sherrin in his hands in the final moments.

“I knew it was late (in the game) … and with that the final siren sounded and that final siren eclipsed everything I had ever experienced in sport,” he said.

“Everyone has their ups and downs. I had mine, my teammates had theirs. But for all the passionate Fitzroy supporters and the Brisbane Bears supporters, with all the turmoil they’d gone through, it was special.

“I remember months later sitting having a coffee sitting on the beach at Mooloolaba and thinking ‘shit … we won. How good is that?’”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Kingsley at a loss after worst defeat of his three year tenure

GWS coach Adam Kingsley admits he's at a loss to explain his side's 88-point thrashing by the Bulldogs, their worst defeat under his leadership.

Attack, attack, attack: Dogs doing it the Blighty way

23 goals in the past week between Sam Darcy and Aaron Naughton has switched the Dogs’ narrative in a masterclass that has legendary coach Malcolm Blight's premiership theory ringing true.