Australian Football Hall of Fame 2021: Chris Judd, Nathan Burke both honoured for amazing contributions

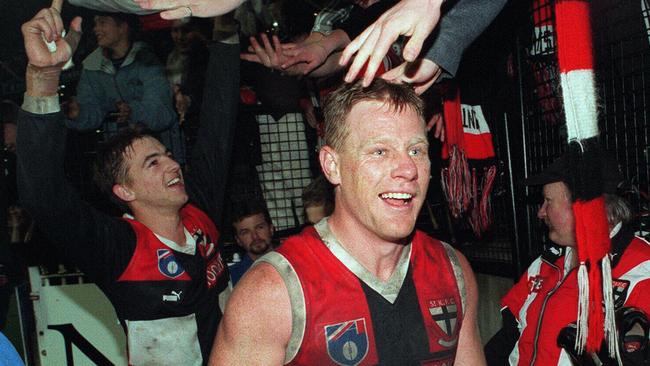

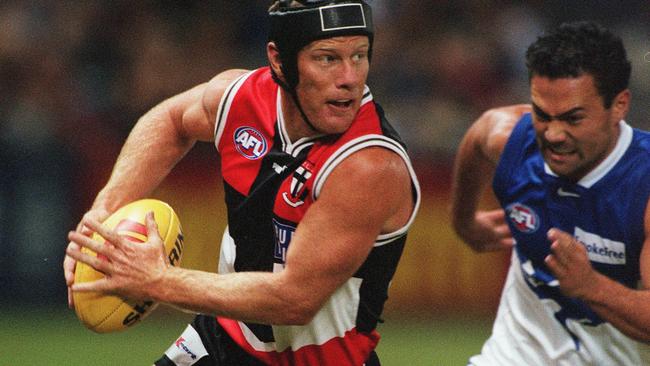

Nathan Burke didn’t have the sidestep of Robert Harvey or star power of Tony Lockett. But across 323 games, few were more willing to sacrifice for the St Kilda cause.

AFL News

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Gary Ablett Sr’s perfectly executed elbow to the head taught Nathan Burke the limits of his body — and brain — with the remedy becoming the trademark of a Hall of Fame career.

Coach Darrel Baldock issued to him the leave-no-stone-unturned mantra that to this day gives him peace despite that harrowing 1997 Grand Final defeat.

And dad Barry, who would hand him 50c for a pie and coke as the thirds kicked the dew each Saturday at Frankston’s Pines football club then expect to see him back on the last siren of the senior side he coached?

Barry Burke’s lessons of those junior years still echo in son Nathan’s ears 18 seasons after he retired.

Watch every 2021 Toyota AFL Finals Series match before Grand Final. Live & Ad-Break Free on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-days free >

They have ultimately secured him the Hall of Fame elevation he believed he might see him overlooked for more decorated AFL premiership champions.

Nathan Burke didn’t have the sidestep of teammate Robert Harvey or star power of Tony Lockett or the commanding presence of Stewart Loewe.

But across 323 games, four All Australian trophies, three Trevor Barker awards and 11 Victorian jumpers, few were more dependable, more consistent, more willing to sacrifice to the St Kilda cause.

“Look, I figured out early on I wasn’t going to the player who was high-flying, who was taking spekkies, who was kicking left-foot snaps over my shoulder.” Burke said this week.

“It was a case of needing to find something so the coach wants to put me in his team. My father and I were discussing it and what we came up with was I was going to be most competitive bugger this coach has ever seen.

“If he wanted someone to slide into mud and force a ball up, if he wanted someone to follow the opposition player around, if he needed someone to stick their hand up for a job, that was going to be me.

“And fortunately at the time coaches liked that thing. I realised I wasn’t super-talented so I needed to leave no stone unturned in every other aspect of playing the game.

“So I was a competitive bugger for my first five years, until Kenny Sheldon was the first one who said I think you can be more than the nuggety back pocket who does that. I want to play you in the midfield and give you the opportunity. That was 1993 and it was my first best-and-fairest.”

Burke might be downplaying his raw talent — as a Richmond tragic zoned to St Kilda he played a season of Under-19s then in the following year played two Under-19s games, four reserves games, then the final 16 senior games and never looked back.

It was in that year of senior football that Baldock made that cherished impression.

“I can remember it vividly. He said, “If your career lasts one game, five years, 10 years, 15 years, I want you to promise me you will look back and say, “I had no regrets”. By and large I look back and think I got the most out of myself.”

But as a player with seven coaches across 17 seasons at famously combustible St Kilda, every brief period of success was followed by crushing disappointment.

In 1991 the young Saints rallied to 14 home-and-away wins but had their spirit crushed Geelong in an elimination final, then a mid-90s rebuild saw them march all the way to the 1997 Grand Final.

Crushing defeat followed and Burke would not play another winning final in his six seasons until his 2003 retirement.

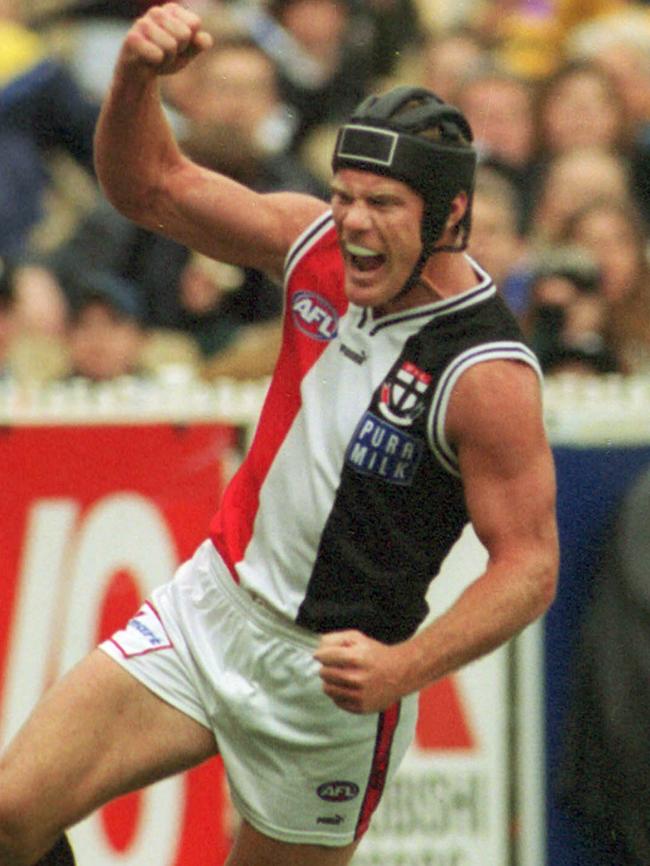

It was in that 1991 final where Burke’s history of concussions came to a head and saw him eventually don the helmet that he would wear for the next 11 seasons.

“I have never really been knocked unconscious but when I got a knock within three or four minutes I would get blurry eyes and I would have a small field of vision then after a game I would get headaches and nausea similar to a migraine. We never used the concussion word which was a godsend because I would say, “Hey, I haven’t been concussed, I can play the next week”.

“In that (1991) final we had finished third and Geelong were sixth. I can’t remember but I have seen the replays. Craig Devonport picked up the ball on the wing and I looked to shepherd and Gary Ablett was bearing down on me at 100 miles an hour and basically I took a forearm to the head that sent me spinning.

“Not long after that he collected David Grant as well and we were both sitting on the bench at Waverley and Plugger (Lockett) was kicking nine at one end and Billy Brownless eight at the other.

“The crowd would roar and we would say, “Was that us or them?” We only had two on the bench and Paul Harding and Lazar Vidovic wanted to come off but couldn’t. If we had got through we might have been a good chance to win it.

“But Kenny Sheldon eventually said you can’t afford to go off all the time. So try a helmet or something.

“I wasn’t that keen but if meant being sidelined or looking silly but running around on the field I would do it, and anecdotally I had less issues wearing it. And it was blatantly a form of concussion but at the time it wasn’t diagnosed so you kept rolling with it. You did some stupid things in those days.”

By 1994 Sheldon was gone after just four seasons, with Lockett (Sydney) and Danny Frawley (retirement) following him not long afterwards.

“He was gone prematurely, he had coached for four seasons and he was the second-longest serving coach in St Kilda history at the time. As St Kilda did, they had a propensity to make bad decisions. They were always looking for a coach to put the icing on the cake, and so Kenny went.”

Yet St Kilda would build again with Stan Alves and a senior core that included Burke, Robert Harvey and Stewart Loewe as they entered their prime.

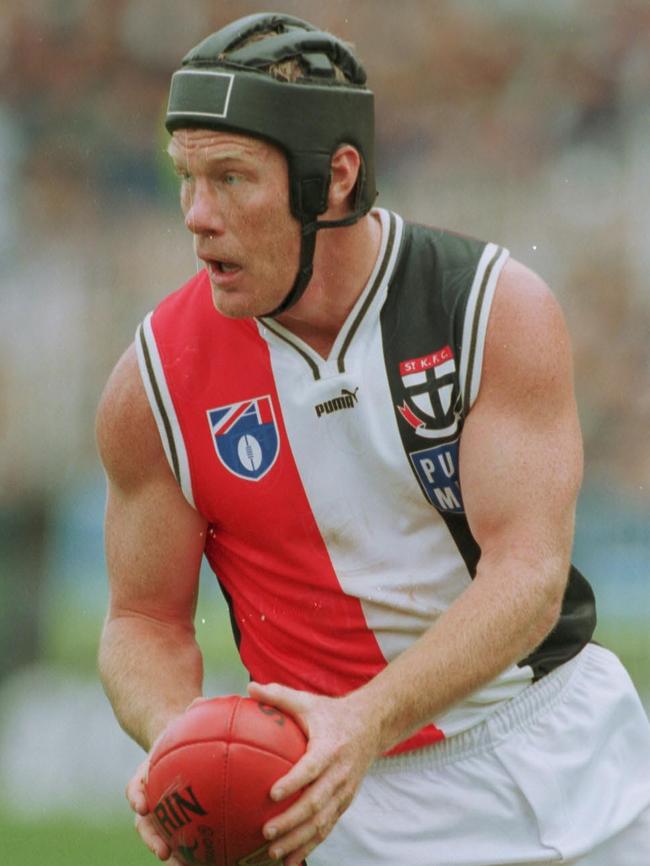

He is proud to have helped driven standards to a new high as he and co-captain Loewe helped drag St Kilda into the 1997 Grand Final.

He would stand tall — 33 possessions on Grand Final day — but Adelaide would turn a 13-point halftime deficit into a 31-point victory as Darren Jarman (6.2) and Andrew McLeod ran riot.

“We didn’t win it, but I would rather get into one and lose than not play in one at all,” Burke says.

“The whole lead-up was amazing, there is nothing in my life that will warrant me being driven through the streets of Melbourne with people throwing streamers at me, but on the day Adelaide were better than us.

“If you are going to lose you might as well lose thinking you played OK, it certainly beats having a stinker, but it’s a team game. People talk about Jamie Shanahan playing on Darren Jarman but Andrew McLeod won the Norm Smith as a midfielder and that was our job to stop it.

“It all just happened so quickly. We were in front at halftime and then they just went bang, bang, bang.”

Within 12 months Alves was gone, replaced by first-time coach Tim Watson, and although Burke would play on to 2003 his chance at a premiership had vanished.

“I think the same issues that got rid of Kenny were the ones that led to the downfall of Stan. Again we looked for someone to put the icing on the cake and unfortunately we went for someone who had never coached before. It was a weird decision and we ended up chasing tail from there, but that’s the history of the St Kilda football club.”

Burke learned loyalty from the likes of Trevor Barker and Geoff “Joffa” Cunningham and professionalism from his great mate Robert Harvey.

But there was only one Danny Frawley, the inspirational captain who defined what it meant to be a Saint.

“You talk about the heart and soul of a football club, when Barks and Joffa left their legacy was shouldered by Danny in a really large way. He took up the mantle and single-handedly carried it by himself. The only way you can console yourself with his loss is that it’s a mental disease. Having that conversation with Spud and saying, “Hey, are you OK” is not going to overcome a disease. It requires more than that and it’s the only way you can really reconcile and console yourself when you think you should have done more.”

Post-football, Burke has continued to devote himself to the game as a St Kilda board member, match review panel member and now Western Bulldogs AFLW coach.

Daughter Alice now plays for St Kilda’s AFLW team carrying on her father’s rich tradition.

“I just love the game,” Burke says.

“Any way I can stay involved I will. I just want to see the game across its different facets. And now with the AFLW, to be totally honest I can’t remember a time in the game that I have enjoyed as much as coaching in the AFLW, I was walking with my wife this morning and she said, “Do you see it as a job?”. And I said,“ I don’t, I just love it”.”

AFL football one day, Judd added: “I couldn’t see it on the horizon, but given what we have all lived through in the last 18 months, you have to be careful in predicting the future.

“For the time being, though, there is a full book of what is going on.”

WHY JUDD THOUGHT SUPER DRAFT WAS ‘OVERHYPED’

Glenn McFarlane

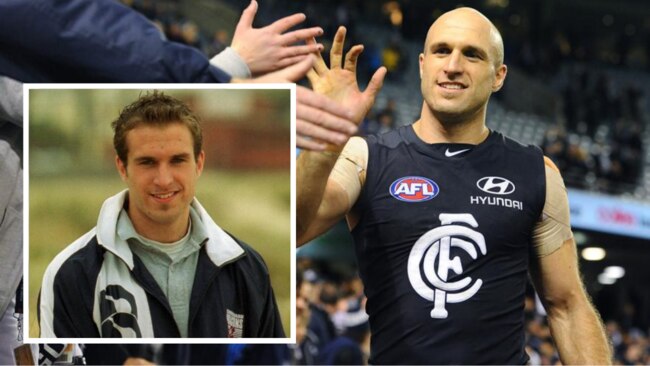

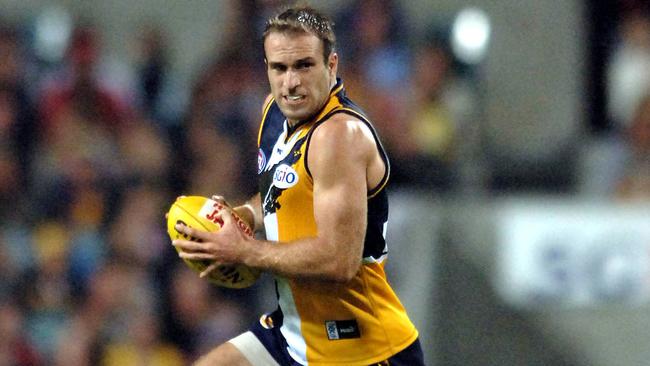

It was the explosive half that helped launch Chris Judd on his pathway towards greatness.

On a Sunday afternoon at the Gabba in 2003, and in his 34th AFL match, 19-year-old Judd turned on the afterburners against Brisbane, kicking five first-half goals in less than an hour.

His explosive speed, his evasive capabilities, and his superb finishing skills were on show in a match that he is still remembered for almost 20 years on.

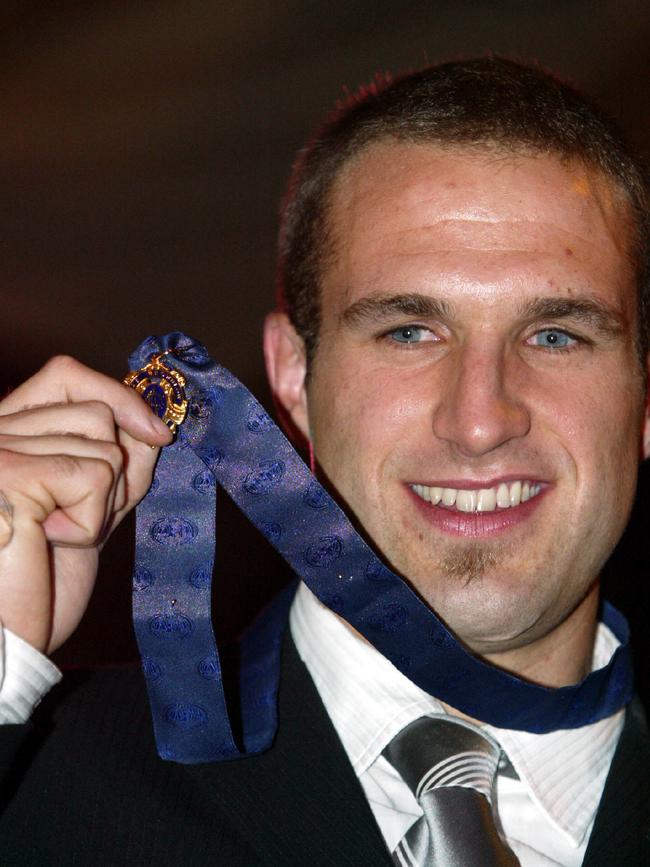

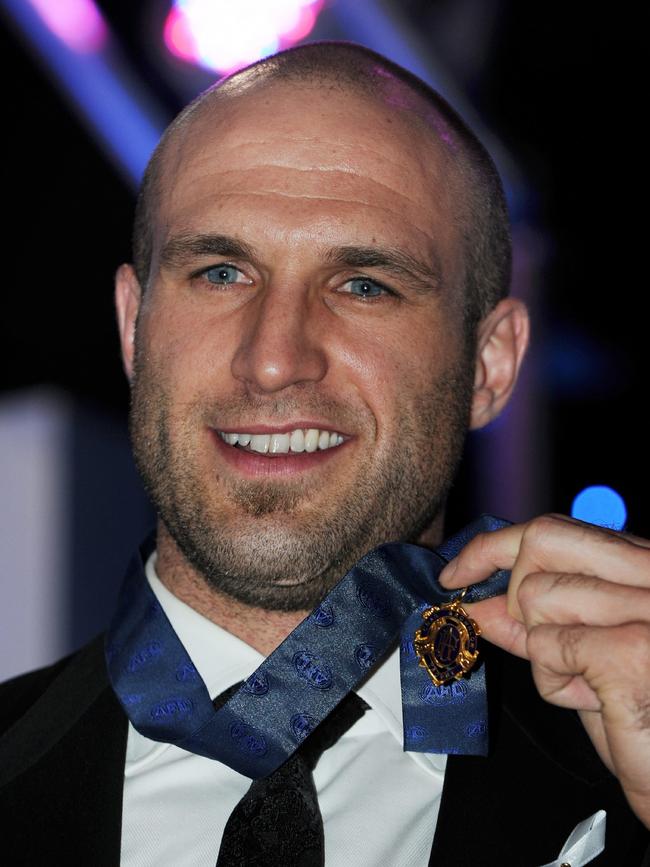

“It’s one that people remember and it has come up this week a bit, too,” Judd, now 37, said this week as he was elevated to the Australian Football Hall of Fame on Tuesday night in his first year of eligibility.

He sees that moment through a slightly different lens.

He doesn’t think so much about his own performance that day, but the Eagles’ effort to systematically outrun the all-conquering Brisbane Lions, who would win a third successive flag later that season.

“It was a bit of a watershed game for the football club at the time,” Judd recalled this week.

“No one could beat them (Brisbane) at the time. We had been up there the year before and got smashed by about 80 points, but we got bashed up too.

“To go back to their home ground and have a win (by 69 points). I think that instilled a lot of confidence that the path we were on was the right one.

READ NATHAN BURKE’S INCREDIBLE JOURNEY BELOW

“Brisbane was so much bigger than other teams. The message from the West Coast coaching and playing group was that we weren’t going to try and bulk up. We were going to take running to the next level, to try and just be light, and to almost use (Brisbane’s) heaviness to expose them, rather than trying to outmuscle them.”

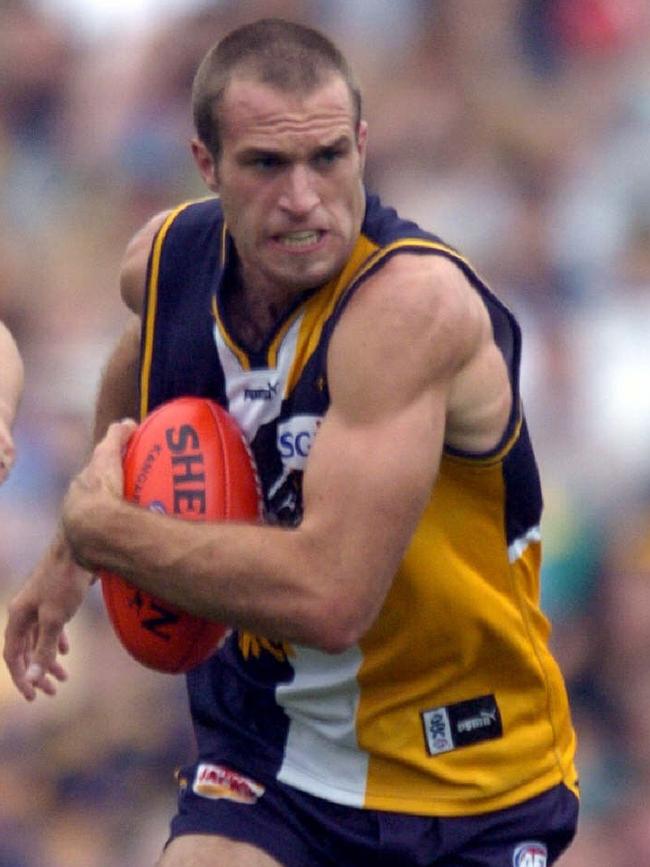

West Coast would make a Grand Final two years later, heartbreakingly losing by a point. Within three years, the Eagles would be premiers.

Two Judds

The colour of the guernsey wasn’t the only difference in the first and second stages of Judd’s career.

Judd the Eagle became a template for the breakneck pace that defined West Coast’s era, which a young Patrick Dangerfield said all midfielders have since modelled themselves on.

The older, more experienced Judd we saw in his Carlton years was just as impressive and equally inspiring for his teammates, but he played in a different manner.

Groin issues in his final year at the Eagles robbed Judd of some of his explosiveness. So he changed his craft to become a clearance-winning, inside-midfield at the Blues.

“I had some injuries at 23 as all players do and probably never quite had the same level of speed, which meant I had to adapt and evolve,” Judd detailed.

“I become a bit more of an inside mid and a bit more of a grunter (at Carlton).

Judd spent six seasons at West Coast (134 games from 2002-2007) and eight at Carlton (145 games from 2008-2015).

“I walked into West Coast with a pretty young group filled with heaps of talent, plenty of drive and a world class footy club,” he said.

“At Carlton, we didn’t reach the same heights, but we had some young talent and a group of senior players trying to chase success.”

Asked about his elevation to the Australian football Hall of Fame on Tuesday, Judd said: “The call was a buzz. It is just a reminder of the fortunate career I was able to have.

“I’ve been five years out of the game now. I almost feel like a different person.”

Super draft

Judd didn’t initially subscribe to the 2001 ‘Super Draft’, wondering if it had been overhyped by a new TV rights deal.

“I wasn’t sure if it was a really good crop, or if it was just the first year of Fox Footy and the first year where draftees became a bit like celebrities because of the changes in the footy media,” he said.

“A lot was made of myself and Luke Ball and Luke Hodge. But when you look at it in hindsight, it was a pretty good crop. Jimmy Bartel and Gary Ablett and Nick Dal Santo and Dane Swan … it was probably a lot deeper than usual.”

Judd had only been interviewed by four clubs leading into the draft.

“I thought I was going to go to St Kilda, Hawthorn, West Coast or Fremantle. The first six picks went to those four clubs. I didn’t even speak to anyone else.”

Hawthorn went for Hodge at pick one. The Saints took Ball to two. Judd, from Caulfield Grammar, was off to West Coast at pick three.

“My initial reaction was I would have loved to have stayed in Melbourne,” he said. “But in hindsight, I was lucky to go to the Eagles.

“They are the sliding doors moments you have in footy.

“I look at my kids now, and I wouldn’t have them if I hadn’t gone to Perth, and I wouldn’t be married to Bec.”

Judd was overlooked for West Coast’s Round 1, 2002 match, playing his one and only WAFL game with East Perth.

He kicked four goals, and East Perth’s coach Tony Micale prophesied: “Well, that’s the last time you’ll see Chris Judd wearing an East Perth jumper.”

Judd debuted as a late inclusion against Collingwood the following week, earning praise from Mick Malthouse, who would later coach him at Carlton.

Stress factors

Judd won two Brownlow Medals — as a 21-year-old with West Coast in 2004 and as a 27-year-old with Carlton in 2010.

“It was such a huge honour,” he recalled of his first Brownlow. “In hindsight, I found it really stressful. It was just the expectation that came at such a young age.

“I was not really at an age where I knew how to deal with it. The only solution was to double down and work harder.”

Judd said that pressure meant he was “uptight (through) my whole footballer career.”

“I just think it stemmed from having so much pressure and expectation, particularly early in my career,” he said.

“When you look back, you realise the happiest you are as a footballer is that 15-minute window after you’ve had a win.

“You look at what players have to overcome playing contact sport. They have to overcome fear … the idea of people rocking up to a workplace and potentially getting kneed in the head or knocked out, or physically changed forever.

“They are dealing with the fact they don’t want to let their teammates or coaching staff down. There is the idea of a loss or poor performance, not just the physical reasons behind it, but also the shame that comes with that.

“I felt the ability to be able to reach somewhere near my potential physically with a group of other like-minded people was really special.

“But there was a huge amount of stress that came with that.”

Eagles, Swans rivalry

West Coast and Sydney played two pressure-packed Grand Finals with a collective margin of five points.

The Eagles lost the first by four points after a Leo Barry mark saved the game, with Judd’s 29 disposals earning him the Norm Smith Medal.

A year later, West Coast won by the barest of margins.

“In hindsight, it was almost fair that both clubs got one all,” Judd said.

“The disappointment of 2005 was enormous, but it never felt like the end of the story, because we were so young. You are a bit stupid at that stage, and you don’t realise the moving parts that are required to get to the last Saturday in September, let alone win it.

“It felt like (2005) was a stepping stone for us, and it turned out it was.”

Judd was the Eagles’ premiership captain in 2006 after Ben Cousins’ off-field indiscretions cost him the role.

“There were plenty of headlines at the time and there was a lot going on,” Judd said. “But everyone was able to dig in, stick together and end up coming away with the chocolates.”

Blues bound

Judd hadn’t factored in the media frenzy he created when he decided to return to Victoria at the end of 2007.

“It was a non-football decision,” he said. “I knew I would end up in Melbourne post-footy and it made sense to do it when I did.

“I wanted to make a meaningful contribution to the new club.”

He met with four clubs — Carlton, Collingwood, Melbourne and Essendon — but remains bemused he was criticised in the media for “interviewing” clubs.

“Some people were saying ‘I can’t believe Chris Judd is interviewing clubs’,” Judd said. “I was meeting with clubs. How else would you do it?”

Judd settled on Carlton as he believed at the time the Blues were on the right pathway.

“(Carlton) looked like it had the potential to replicate West Coast’s journey,” he said. “It didn’t quite turn out that way. But by the same process we had some good years and we moved up off the bottom of the ladder to play finals for a few years.”

Finals

Judd played in four finals series with Carlton, with his highlights being elimination finals wins over Essendon in 2011 and Richmond in 2013.

“2011 was probably the highlight of the years I was at Carlton,” he said. “The team was playing well, we had some new assistant coaches and Marc Murphy had a magnificent year.

“I remember we beat Essendon at the MCG and Murph had almost 40 (disposals), we had Kade Simpson, Heath Scotland and Eddie Betts and guys like Andrew Walker.

“We didn’t keep improving and once you stop improving, you move down the ladder fast.”

Judd’s career ended abruptly in his 279th game after he suffered an ACL in a Round 8, 2015 clash with Adelaide.

“I was probably done for a couple of years (before the injury),” he said. “Professional athletes get pretty good at lying to themselves … you tell yourself you still have a bit to go.

“That injury took it out of my hands. It was the right time to go.”

Future

Judd has stepped away from the Carlton board with plans to spend more time with his four children — Oscar, Billie, Tom and Darcy.

He still follows the Blues and keeps an interest in the Eagles.

“Every decision I made from 16 onwards was based around football,” he said. “I put a huge amount in, but I was one of the ones who got more back from the game than I gave.

“I am happy that my life isn’t centred around it anymore.

“To have a family who is healthy and very busy is a good situation.”

Asked if he could see himself back in a role in