Local football legend Alan ‘Dizzy’ Lynch’s family donates his brain after suspected CTE contributes to his death at 70 from Parkinson’s

Local footy legend Alan ‘Dizzy’ Lynch died on Tuesday at the age of 70 with suspected CTE. As MARK ROBINSON writes his family is hopeful his final act of donating his brain for research can be his greatest legacy.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There are few more emotional experiences than watching a loved one die in palliative care.

In the countdown to inevitable death, the checklist of emotions is something like foreboding, reflection, humour, immense grief and finally process, both mentally and organisational.

The Bromley family lived all of that in the final days of the life of Alan “Dizzy” Lynch, who died on Tuesday from Parkinson’s disease. He was just 70.

So organised was the family, Dizzy’s brain was delivered to the Australian Sports Brain Bank the day after because Dizzy and his family were determined to learn if the 15-or-so concussions he suffered during a lifelong dedication to football had turned his brain to mush.

Part of the forgotten generation of footballers – those who played in the 1970s and 1980s at all levels – the family suspects Dizzy had classic symptoms of CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), which is a degenerative disorder that kills nerve cells in the brain and likely is caused by repeated head injuries. It can only be found post-mortem.

“The brain bank is amazing,’’ Jenny Bromley said. “The organisation is there for people to donate for research and it’s a way to keep giving, even when we die.

“You’ve got to find something positive among the grief, something to hold on to, something to hope for.

“The feeling is ‘what can we do now? How can we make this better, not better but what can we do?’ That’s why Dizzy wanted to donate his brain, like, ‘how can we continue to make footy safer?’

“It still has a long way go, but we are getting much more awareness that this is a real issue, that we have to keep our amazing sport, but we have keep it very safe.’’

Bromley was Dizzy’s partner for three and a half decades and is the mother of their four children – Jess, 36, twins Josh and Sam, 30, and Tommy, 26.

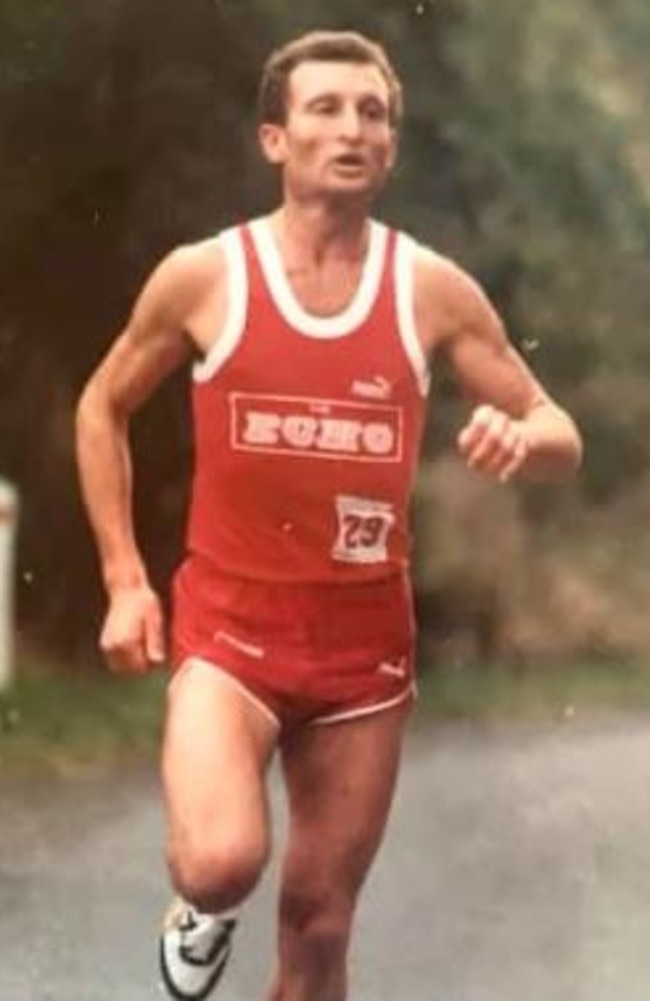

Dizzy was a renowned sportsman, coach and life teacher. Footy was always his favourite, although he excelled at running too. He was Stawell champion in the mile and two-mile category and was inducted into the Stawell Hall of Fame as a legend.

In his final days at Ocean Mist Aged Care in Geelong, running mates from all over came to say goodbye.

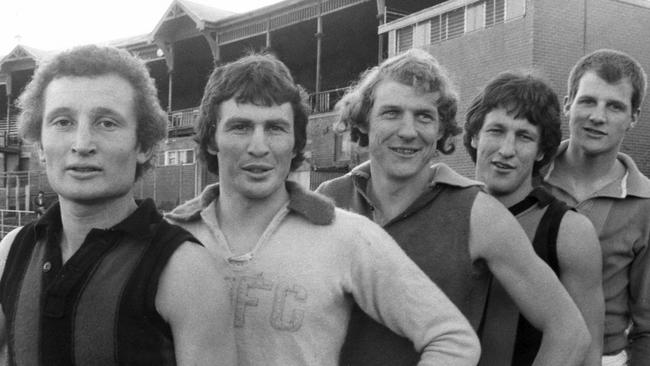

But footy was first and foremost. He played for North Shore, Geelong West in the VFA, for Richmond (two games) and Footscray (five games), for North Ballarat where he was a premiership captain and coach, for Beaufort where was also a publican and he also played in Tasmania and in Western Australia.

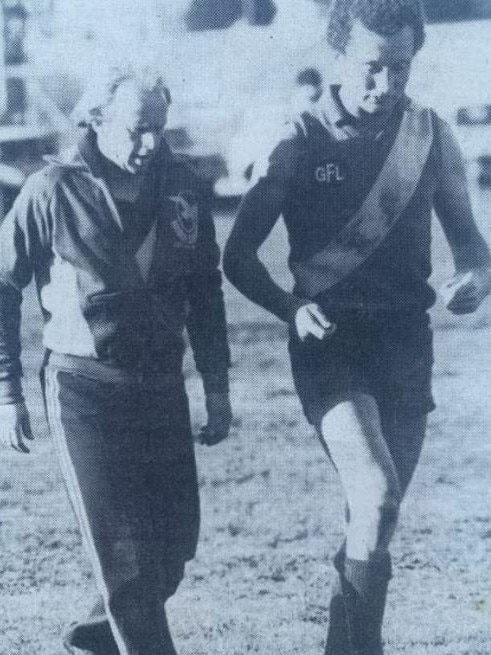

People who know him say was never a champion per se, but a good bloke who was hard at it and had a determination that personified great bush-footy players.

Footy in the 1970s was frontier footy. Aggressive and often violent. Concussion – or brain trauma – was part of the game. You gave it and you wore it; and it was an inconvenience more than anything else.

The world is wiser now and Bromley, who is on the board of the Community Concussion Research Foundation, which is chaired by Prof Mark Cook from the St Vincent’s Hospital neurology department, wants the world to become even wiser.

“I don’t know what the brain bank is going to uncover; and if that’s what he has, CTE, then maybe this can help more studies and research and education,’’ she said.

“If it does show CTE, that’s one more case to show that we do need to make this sport safer.”

A fabulous life changed about a decade back when Dizzy begin acting differently and then, in 2017, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

“He didn’t have every side of Parkinson’s – he didn’t shake – but there was certainly a decline in his memory, he would stop mid-sentence, he’d have a blank stare, and it got to the stage where he would get lost,’’ Bromley said.

“He couldn’t look after himself and eventually had to go into care about two years ago.

“As a family, we tried to make sure we kept in the moment. We couldn’t think forward too far. We all became carers and we tried to keep everything simple.’’

Footy was large in their lives. The three boys played – Tommy still does at the Roosters – while Bromley is part of the Lockett clan and for a period, she was president of North Ballarat in its VFL days. Her affection for the game has waned, she says.

“I love how football clubs are a great part of society, the connection, culture, the community, I do love football, but I absolutely don’t love the ramifications of what can happen if it’s not safe,’’ she said.

Bromley, a school principal, doesn’t have a hate bone in her body, but admits to disappointment she has with the AFL and AFLPA.

Asked if the two bodies were supportive in her endeavours to find support for Dizzy, she said: “No. I don’t know what to say, really. I don’t think Dizzy was a big enough name.”

Asked if she believed the two bodies needed to help players who played in the VFL, regardless of how many games they played, she said: “Absolutely.”

“I just wonder about their legitimacy in this area, really,” she said.

The day after their dad’s death, the twins, while driving back to Ballarat to be with family and friends, harboured all the emotions.

The palliative care experience had been a “beautiful struggle”, Josh said.

Stories about footy, about athletics, about Dizzy’s love for a catch-up coffee and about summer camping holidays at Port Arlington bounced around the room. As did the tears.

Josh: “Through the palliative care period there was hell of lot more laughter than tears. That was an accumulation of many years of energy that Dizzy put into all of us and who he touched. The deterioration in the last couple of years has been really difficult. The last meaningful conversation we had mutually was probably two or three years ago and not being able to talk to your dad, and this is for neurological diseases, but not being able to talk to your dad … I would say the palliative stuff was a beautiful combination of joy and sadness and memories. It was a struggle but a beautiful struggle.”

Sam: “I struggled with the deterioration of dad for quite some time. There were moments when I didn’t want to go and see him. It’s hard seeing your dad the way he was towards the end. Dad probably should’ve passed away Sunday or Monday, but he did that palliative care process just like he played his football, he was tough and didn’t want to give up. That’s the way he wanted to go, just fighting.”

Despite them believing footy swiped from them their old man, they don’t blame the game. The pair also played footy for North Ballarat, albeit their final seasons were enveloped by dad’s predicament.

Josh: “Yeah, I do love footy because without footy I don’t think dad would be the person he is. I love what footy brings out in terms of teamwork, selflessness and connection to community. That was the main part of football that dad loved.”

Josh works at the Geelong Falcons as a wellbeing co-ordinator.

“It would’ve been a perfect role for dad back in the day,” he said.

Sam: “Do I like footy? I have a different relationship with footy than I used to. I’m not playing anymore due to the fact I‘ve had a few concussions in my time. Maybe eight to 12 that I could truly say that was a confession. It’s taken me a few years to realise I’ve had a lot. I just didn’t have the education five years ago, and then watching dad probably from about 2019, it really started to hit home that dad was on a pretty bad path. I was very anxious in my last year of footy, like, extremely anxious. Like Josh, I still love the other side of footy, the connection, the relationships, trying to get the best out of yourself, the team aspect, but there’s definitely things I look back at now where I would’ve done if differently.”

Josh: “I got a concussion three years ago and if I had got that concussion four years earlier, I probably would’ve been less cautious about it. I was cautious about this concussion through watching what was happening to dad, and hearing stories of ex-footballers and ex-rugby players as well. The coverage concussion has been so much more exposed.’’

The twins hope their dad’s death and how it eventuated, and the suspected outcome of the brain bank tests will leave a legacy.

Sam: “Who knows what’s going to be found. Science still has a long way to go to figure out concussion and how the brain reacts. I’m looking forward to finding out the results, and then allowing people to learn the lessons, and to educate people.”

Josh: “I think it’s a nice legacy. Say if we had the education we have now, and what we’ll have in the future, and dad had it back then, he probably gets ruled out of playing footy when he was, what 26? And that would have given him a chance to have a great, healthy, long life. I just wish the education we have now was around then because it could’ve changed the course of dad’s life.’’

Sam: “Dad played a handful of games at VFL level, but I think he’s a great pin-up boy for high-level country footballers who had a go at VFL level. It’s not just AFL players who get concussed, it’s country-level players as well, thousands of them, and unfortunately they don’t have the education or resources. Maybe that can be a bit of dad’s legacy as well, all these local-level players who are dealing with it.”

Their message is not of anger, but of awareness, which includes AFL commentators sceptical and dismissive of concussion stories. Josh says those commentators have not lived with someone with a person with CTE symptoms.

“I think it’s on the people who talk about it to get a good understanding of it,” he said.

“I know people have a job to do in terms of talking about footy, but sometimes they have to really think about the impact this does have on people. We’ve seen it.’’