Jon Ralph: The system will never be perfect, but aspects of the illicit drugs policy have been the AFL’s dirty secret for far too long

What if a player’s sample is negative and the drugs they took are not revealed by an ‘off the book’ test? The answer is the most jaw-dropping aspect of the drugs bombshell, writes JON RALPH.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

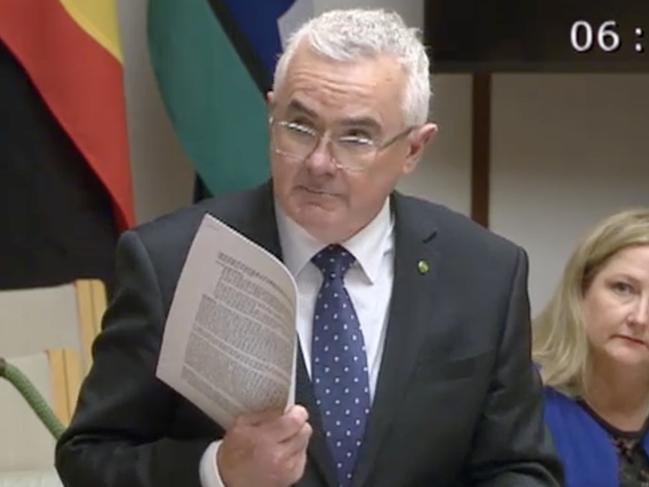

The most jaw-dropping aspect of Andrew Wilkie’s parliamentary bombshell was the part of his revelation that he failed to bring full circle.

Wilkie talked about secret drug tests under the AFL’s medical model that saw players withdrawn from matches if their drug testing data lit up like a Christmas tree.

But what happens if a player’s sample is negative and the drugs they took are not revealed by that test.

The horrifying reality – laid bare for the first time – is that those players are then allowed to play that weekend.

So under the league’s own policies, players who the AFL’s medicos and club doctors know have admitted to drug-use only days before scheduled games are allowed to play. Out you go mate, the coast is clear.

The AFL’s doctors might say those players with addiction issues and mental health problems need the carrot of football as an incentive to work on their behaviour.

Deny them football entirely and they might spiral even further.

But to look back at summer’s most recent high-profile example – no names, no pack drill – is to realise that denying some players the chance to train and play is the biggest incentive for them to get their life in order.

If players are placed in the medical model – exempt from positive drug strikes, despite regular testing and supported with counselling and education – it stands to reason they should be removed from playing football until they get their lives in order.

A football field with all its attendant risks of concussion and other injuries is surely no place for someone battling drug addiction or for someone who has admitted to taking illegal substances in recent days – on occupational health and safety grounds at the very least.

And, yet, under this policy, players are allowed to play-on, as long as the league can be sure WADA will not be on the scene with a post-game urine test that might be positive.

So instead of a two-strikes policy, we have some players immune from positive strikes and yet still gracing our fields.

The AFL’s illicit drug policy should be a prevention and welfare model.

Players shouldn’t be named and shamed. And if a confected excuse about a tight hamstring or delayed concussion or personal issue is needed, then such is life.

But the reason the footy public has so little faith in the illicit drugs policy is that the medical model seems full of grey areas. And the ratbags, scallywags, and outright liars seem to be having a field day with the loopholes this policy provides.

From self-reporting to drug strikes dropping off their records after a given number of years, to the simple lack of tests that allow them to game the system.

The AFL will continue to cite these loopholes to say that they have helped some players, and no one denies that fact.

The AFLPA can talk all they want about the illicit drug policy being voluntary, but they know if there was no policy, then drug use would skyrocket.

And there would also be more players ensnared on long ASADA bans through game-day tests or unwittingly taking illicit drugs laced with banned substances.

So spare us the nonsense about withdrawing, just find a way to vastly improve the policy.

It is not hard to frame a policy that has such regular testing that it scares the social drug users.

The last public numbers from the AFL had 1998 tests recorded for 15 first strikes and a single second strike before the league and AFLPA made that number confidential.

So players could expect to be tested twice, or perhaps three times, each year.

It would be laughable if this number was not a total of 5000 under the new policy.

It would mean every AFL player could expect to be tested five or six times a season.

At Friday morning recovery sessions after Thursday games – exactly when they might expect to take advantage of a long weekend to dabble in illicit drugs.

As an entire playing group being tested, not six players plucked from a list of 42 so the player who has taken drugs feels like he can roll the dice that his name won’t come up.

With exhaustive hair-testing so a player like Bailey Smith, lustrous blond locks and all, can’t go on an off-season bender without fear he will be relentlessly target-tested for the entirety of the following season after those drugs are detected in his hair follicles.

Better for the AFL to have 40-50 positive tests each year – even if they are not publicly released – but know the extent of the problem than to bury its head in the sand.

Because as players like Jon Hay and Brock McLean have testified in media interviews in recent years, the illicit drugs code never scared them off drug use.

At least if the public knew the testing was hugely ramped up and had a level of confidence in the procedures, it would be easier to cop the ridiculous pretence that this is a punitive model.

They could believe players were in safe hands, even if not publicly exposed.

Even though there have been a minimum of 20,000 tests taken since the numbers went underground and not a single player outside the medical model has tested positive twice.

The system will never be perfect, but aspects of this policy have been the AFL’s dirty secret for far too long.