How the AFL has nailed equalisation compared to other leagues around the world

We’ve had eight different AFL premiers in the last decade. MARK ROBINSON speaks to a man that helped pave the way to deliver the most important ingredient in sport – hope.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Almost 40 years after Colin Carter helped produce the AFL’s “Blue Book”, which paved the way for the adoption of equalisation and expansion, Carter on Grand Final morning was like a grandfather gushing over his grandchildren.

“You do know,” he said from his beach holiday home, “that no matter who wins today, Brisbane or Sydney, it will be the eighth different premier in the past 10 years.”

He further offered his delight at the evolution of an even competition by acknowledging that at Round 21 this season, nine teams – or 10 teams if you were an optimistic Essendon fan – were well-placed to win the premiership.

Further again, he said: “The thing that has been pointed out was that three weeks ago, if James Sicily hadn’t hit the post, if Joe Daniher had missed that shot from the boundary, and if Isaac Heeney kick from 70m out hadn’t gone through, there would’ve been three different teams playing in the final stages of the season. How close can you get?”.

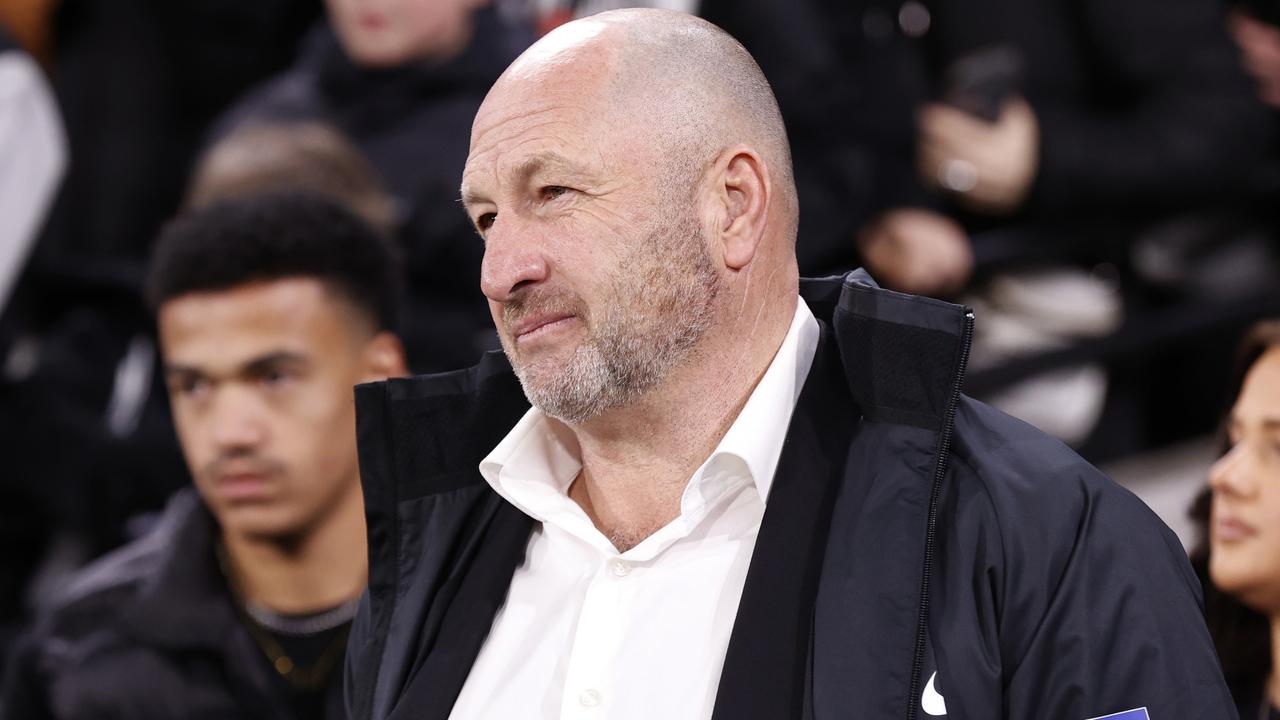

Carter, an AFL consultant in the 1980s, then AFL commissioner from 1992-2008, then Geelong president from 2010-2020, and then a consultant to the establishment of the Tassie Devils, is one of the most influential figures in AFL history.

And he knows history. His fight to have the AFL recognise that the VFL-AFL football competition began in the 1870s and not in 1897 – as official history records it – will continue unabated. That’s a labour of love for him.

In the 1980s, however, it was a labour of necessity. At the time, the VFL competition was struggling and urgently needed a blueprint for equalisation, financial security and national expansion. Hence, the “Blue Book” was delivered.

It wasn’t all Carter’s doing. Peter Scanlon, Graeme Samuel and Peter Nixon were key contributors and they weren’t “football people’’, which was important.

Two were businessmen (Samuel and Scanlon) and one (Nixon) was a politician.

“They stared down opposition from traditional football people and helped institute massive change across the industry,’’ Carter said.

That group was the architect. In 1986, newly appointed chief executive Ross Oakley drove the change.

“The competition was basically stuffed and people were looking for answers,’’ Carter said. “It wasn’t rocket science the path we have to follow.”

Carter and his team did not look towards Europe, but rather across the Pacific.

Domestic soccer competitions in Europe were – and are – boring because only a handful of teams win their leagues. In American sports, equalisation via draft and salary cap mechanisms provided financial stability and promoted hope for teams and their fans.

“In 1985, the VFL competition was uneven, half the teams never figured in finals, the competition was bankrupt and half the clubs were insolvent,” Carter said.

“We looked at all the competitions around the world. There were two competitions that were financially stable. One was the NFL in the US and one was the Bundesliga, but the Bundesliga was very uneven.’’

The Germans were smart. The league threatened clubs: Pass certain liquidity tests or be kicked out of the competition.

“So, nobody was prepared to spend more than they earn,’’ Carter said.

“We looked across at the English competition, and two thirds of the clubs were bankrupt because they would go broke trying to catch up with the rich clubs. That left the NFL.

“What we saw the NFL doing, and every competition there has massive inequalities between the rich and the poor, but what the NFL did was basically equalise so Green Bay, a little town, was as competitive as Dallas.’’

Major League Baseball at the time had its issues. The Yankees were winning everything. Changes to the draft and the introduction of salary-cap taxes then evened the competition. So much so, in the past 10 years 10 different teams won the world series.

The four critical components of the AFL’s blueprint were: 1) A salary cap; 2) A draft; 3) Revenue sharing; and 4) Reduced list sizes.

“One of the things that astonished us was the NFL, which probably uses 40 players each game, reduced their lists sizes to about 45. At that stage, VFL clubs had about 100 players in their firsts, seconds and under-19s,’’ Carter said.

“The argument there was we had to stop rich clubs hoarding players.”

It’s taken its time, but the result in adopting these mechanisms is a dramatic evening of the competition.

Carter: “Not only have eight different teams won the (AFL) premiership, but some of the teams that won it are small teams, like the Western Bulldogs and Melbourne – teams that if you had the competition run according to market rules like the European competitions, they would never get a look in.’’

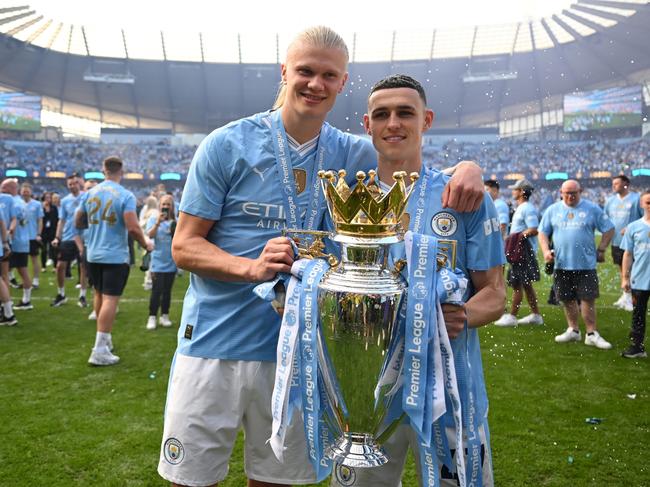

The alternative system, the European system, where one or two teams win every year – Bayern Munich, Barcelona, Real Madrid, Celtic, Paris St Germain, Manchester City and Juventus, for example – would be the stock-standard in the AFL.

“I don’t know what it would look like,’’ Carter said, “but I suspect the West Coast Eagles would have revenues of $300 million and have a $100 million salary and Marcus Bontempelli, Max Gawn and Patrick Cripps would be playing for them.

“The remarkable thing we’ve got, and what the NFL has got, is that every club has basically the same paid players and that’s because of the revenue sharing.’’

The English Premier League is under private ownership and, Carter says, if equalisation measures were introduced, there would remain a constant threat of a breakaway “super” league of rich European clubs.

“One of the risks of the equalisation is you increase that risk a bit, but our teams have got nowhere to go if they ran away,’’ he said.

The NFL and AFL models deliver the most important ingredient in all sport – hope.

That’s all fans want. Of course, they want a well-run club, astute drafting and trading, good coaching and development, but all that is rolled up into hope.

‘’The mantra in NFL – and I would’ve visited six different clubs – is Any Given Sunday,’’ Carter said.

“The real competition, they said, was not between New York and Dallas, it’s between football and barbecues and going to movies and having picnics. And if that’s the basis of competition, you do yourself a big favour if the competition was even because that attracts public interest.

“One of the great ironies is that Europe, which is historically full of democratic socialists, has got the most capitalist football competitions in the world and in America, which is full of capitalists and all the clubs are owned by billionaires, has the most socialist football competition in the world.

“The rich owners know the value of their own franchises is enhanced if there’s an even competition. They got this remarkable view that everybody’s healthy and successful.’’

It’s true that the AFL has never been more even, although St Kilda president Andrew Bassat would disagree. Nevertheless, there are record eyeballs, record attendances and record memberships and, at the end of the season, it seemed there wasn’t a game at the MCG without 90,000 fans there.

The AFL’s mantra, Carter reasoned, was that it’s Any Given September.

“It’s even, there were so many close games this year … we’ve got a wonderful sport,’’ he said.

While there was some reticence from traditional football folk to the massive changes made to the game circa 1985, Carter is proud of the transformation from bankrupt competition to sporting juggernaut.

“I think commitment was there from the start,’’ he said. “ I was always impressed, for example, with Jack Elliott (Carlton president), who I had profound arguments with and didn’t like in a lot of respects, but he agreed the American model was the only way forward. It was right.’’