Footy ‘godfather’ Ron Barassi meant more to Melbourne than the frames of football

Ron Barassi’s humility trumped his strength and his charisma, so the man seemed bigger than his legend.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Long ago we were told that Ron Barassi had already arranged his funeral.

He wanted to reach 100, of course, an endeavour furnished with regular bouts of gym or golf or sudoku.

But Barassi was Barassi. He was prepared. There was even talk at the time of scattering his ashes on the MCG, a notion that disturbed wife Cherryl, who openly wondered if footballers cared to be “sliding around” in her husband’s remains.

We will find out in coming days whether the ashes idea was part of the Barassi plan.

It’s too late for a statue – erected a couple of decades back, it’s long been a meeting place outside gate 4 of the MCG.

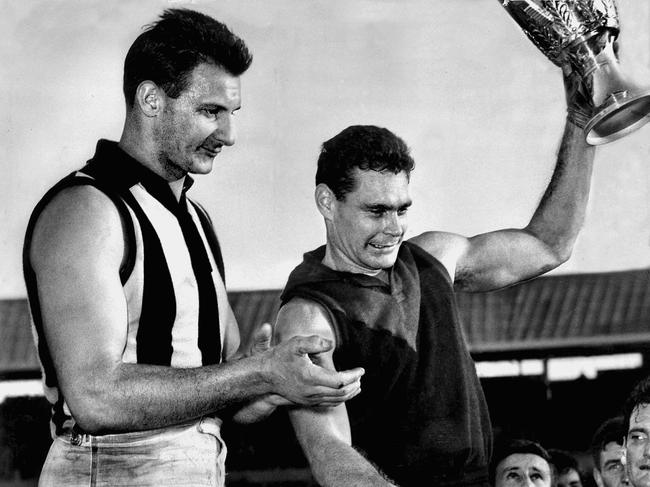

But we are certain to hear more about the clamour to call the AFL premiership trophy the “Barassi Cup”.

The idea is nothing new. Coach and player Mick Malthouse who, like Barassi, thinks outside of footballing cliches, was spruiking the idea last millennium.

It seemed no stranger then than it does now.

As Malthouse wrote: “The key to Barassi is his commitment to the national competition, his willingness to promote the game and, alongside his strength of character and charisma, an outstanding humility.”

Barassi was awarded the Victorian of the Year title in 2009, fittingly for choices that had nothing to do with football.

The tale goes to his defiance at being “defined by a birth certificate”.

He was 72 (going on 30) when he helped a woman being attacked in the street. He got kicked and belted for his trouble.

Yet it might be argued that Barassi had been Victorian of the Year, one way or the other, since Menzies was prime minister.

He embodied an unusual game in an unusual city where titans were larrikin figures called Jack and Lou, and the timetable for life and contentment was reset each Saturday.

Jack, as in Dyer, hulked with menace, and occasionally murdered words. Lou, as in Richards, commercialised impish authority. Let’s not forget Ted, as in Whitten, who was described in death as “a pagan god of these western tribes”.

Yet none of these emblems of the game and its place was mistaken for a “godfather” or a “messiah”. Such labels belonged exclusively to the bloke who started out as “Little Ronnie”, and who will be serenaded by more “The man I knew …” reflections than any other player or coach.

The godfather title denotes Barassi’s singular purpose. He was the coach who – all “Italian gestures” – belittled and bullied his players to motivate them.

As the messiah, everyone paused when Barassi had something to say. The gospel was in session. About Sunday games, say, or a national competition, or the benefits of the “head down, backside up” approach. The topics didn’t matter much, especially later in life when Barassi’s many non-footballing views expressed a curiosity that reached far beyond the game.

When Barassi spoke, everyone listened. When he acted, everyone watched.

His place in Melbourne was never clearer than in the mid 1960s. It was an era of change, when men were seeking to go to the moon and women were finally being liberated, and the world never got closer to blowing itself up.

Melbourne had its own priorities and its own seismic events.

Barassi had triumphed at the Melbourne Demons, as had his departed father. The club boasted two icons – one, coach Norm Smith, had moulded the other, Barassi. And Barassi was being tempted to leave his Demon kin.

The epic episode spoke of Barassi’s nature. He was conflicted by the offer to go to Carlton. His loyalty to his club could not nestle with his need to provide for his three children.

And so a city watched on, mesmerised by the speculations that would wrench the great game from its age-old moorings. Barassi went to Carlton, and people cried. He succeeded there, then later at North Melbourne, as a kind of archetype in masculinity, innovation and intent.

But more subtle qualities began to shine, too. He spoke of regrets. A humble style, informed in part by his Legacy Child beginnings, seemed to dictate that Barassi was unaware of his aura. He had ability, sure, but he preferred to ponder his good fortune.

There was vulnerability, too, expressed more and more in his latter years by a willingness to be moved, and to weep.

Barassi’s firm handshake and twinkling eyes were always there, along with his indomitable attitude to a challenge. He hated losing, whether it was backgammon or a water pistol fight. And he will be remembered mostly in the statistics and the football ecosystem he helped shape.

But he meant more to Melbourne than the frames of football, which he once said was “unlike any other game in the world”.

For Barassi was unlike any other football giant.

Mick Malthouse was right all those years ago. Barassi’s humility trumped his strength and his charisma, so the man seemed bigger than his legend.