Australian Football Hall of Fame 2023: James Bartel, Corey Enright, Sam Mitchell inducted

They were the stars of the dominant teams of the past two decades with multiple premierships, best and fairests and Brownlow Medals between them. And they’re now in the HoF.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is one of the biggest nights on the AFL calendar – the Australian Football Hall of Fame.

And this year’s crop is as star-studded as they come.

Find out what made Sam Mitchell, Corey Enright and Jimmy Bartel champions of the game and how they reacted to the incredible honour.

Mitchell: a refusal to take no for an answer

– Glenn McFarlane

In the champagne and beer-soaked moments immediately after Hawthorn’s 2008 premiership success as most of his teammates reached for the endless supply of beverages, Sam Mitchell was dialling numbers in his phone.

The club’s premiership captain started calling those who had afforded him the only thing he had asked for – a chance.

He knew that if it hadn’t been for the hard work and the encouragement of a number of key people around him, he wouldn’t have held up the premiership cup that day.

Or, as it turned out, he wouldn’t have won those three other premierships with the Hawks later on. Or the Brownlow Medal. Or the five best and fairests.

He called one of his mentors David Parkin, who had given him guidance in his early years at Hawthorn. A surprised Parkin thanked him and suggested Mitchell call his one-time Box Hill coach Donald McDonald, who had been one of the catalysts behind him being drafted.

Mitchell instantly told Parkin: “I rang him before I rang you!”

Having been overlooked in a national draft, and dismissed as being “too small and too slow”, the hardworking, driven kid from Mooroolbark has always known the power of gratitude.

He knew it was a kid desperate for a chance.

He knew it back in 2008 when he reached the top of the footy summit, the first of four journeys there.

And he knows it now, after his elevation to the Australian Football Hall of Fame on Tuesday night.

“This is special,” Mitchell told the Herald Sun of the latest honour in a career adorned with them.

“No one ever thinks about getting into the hall of fame when they start playing football.”

“I think from a life point of view and playing for a long time, you understand that no one gets there on their own. My name might go in the hall of fame, but there are a lot of people who have been significant in my career.

“You don’t get there without tinders of luck along the way, but you have to have the right people in your corner at the right time.”

He breaks that down into three parts – his parents, who ferried him to endless sporting engagements in his early years, his footy family including his coaches and teammates at all levels, and importantly his wife Lyndall and his children Smith, Emmy and Scarlett.

“I started dating Lyndall in 2006 and I hadn’t achieved very much then,” he said.

Mitchell’s CV now reads like few others to played in the history of the game – Brownlow medallist (2012), four-time premiership player (2008, 2013-15), premiership captain (2008), five-time Hawthorn best-and-fairest winner (2006, 2009, 2011-12, 2016), three-time All-Australian (2011, 2013, 2015), AFL Rising Star winner (2003) and Liston Trophy winner (2002).

Is it any wonder his elevation to the Australian Football Hall of Fame has come so soon!

Mitchell’s compendium of laurels were born out of hard work, dedication, persistence and an innate determination to be the best he could possibly be.

He was dismissed by most recruiters during his under 18s years with Eastern Rangers in an age when the football athlete in the mould of Anthony Koutoufides was in vogue.

But Mitchell’s refusal to take no for an answer meant he carried a belief that “they can’t ignore me forever.” He chose to live by the message on the walls of the Eastern Ranges – “If you’re good enough, you’re quick enough … if you’re good enough, you’re big enough.”

Mitchell had two options when he was overlooked in the 2000 draft – join the Box Hill Hawks in the VFL, or go back to suburban football.

Box Hill was offering him $200 per game; he could have received $1000 per game at a local club. But he chose opportunity over money, and in one of the few sliding doors moments of his meticulously planned journey, it proved to be one of the best decisions of his life.

“It was never going to be a financial decision for me,” Mitchell recalled this week. “It never has been. I haven’t had too many sliding doors moments, but that was definitely one.”

His form at Box Hill in 2001 impressed Hawthorn recruiters and it would result in him being drafted by the Hawks as pick 36 in the 2001 ‘super draft’.

It turned out to be one of the most significant draft selections in the club’s history.

He would win the Liston Trophy in 2002, the AFL’s Rising Star award in 2003 and would become the Hawks’ premiership captain by 2008.

By the end of his career, he would have played 329 games – 307 with Hawthorn – with his four premiership medals the sum of a Hawks’ golden era.

“Everything has its own special moment,” Mitchell said of his team and personal achievements.

“If you look at 2008, it was going somewhere where we had never been before … that felt like a four-year season.

“2013 was about getting back to the top again.

“2014 was beating Sydney, who had beaten us two years earlier, Buddy had gone there and on a performance level it was the first game I had played well in a grand final.

“In 2015 it was about the fact no Hawthorn team had ever had a three-peat. even the great teams of the ‘70s and ‘80s never won three in a row.”

Inherently talented but blessed with a growth mindset, and almost ambidextrous with foot and hand, Mitchell was compared early on with footy great Greg Williams, with Parkin once saying he was at least the equal of Williams, if not superior in terms of influencing results.

“I’ve thought about what my competitive advantage was … the idea of a growth mindset was innate in me,” Mitchell said.

“I genuinely believed if you worked hard at something, you got better at it. It wasn’t until I was in my 30s that I realised not everyone thought like that.”

His autobiography was titled Relentless and that word summed up precisely what made Mitchell the footballer and the competitor across 15 seasons.

One of the quotes he used in the book – which summed up his elite preparation – came from legendary boxer Muhammad Ali, who once concluded: “The fight is won … long before I dance under those lights.”

Leaving aside his one season as a player and one season as an assistant with West Coast, Mitchell has been connected to the Hawthorn Football Club since being drafted at the end of 2001.

Now, as Hawthorn’s senior coach, he is charged with leading the next generation of young Hawks, and he knows they will get the same opportunities that he received a generation ago.

That makes more than a little proud of the club that shaped him as a player and shaped him as a person.

“I got drafted at 19 and by the time I was 22, I could talk at children’s school or at the Royal Children’s Hospital, or to a board of directors, that’s what footy has done for me,” he said.

“By the time my career was over, I had completed an MBA, I had finished coaches’ courses and had endless opportunities to go overseas and study.

“This organisation (Hawthorn) helped me achieve that.

“(As a coach) you want your players to have a great life, not just a great career. You want to know that when their footy careers are over, whether that is in 10 years or 10 minutes, that they are going to be OK.

“Footy does that.”

Mitchell knows that footy and family have been exceedingly good for him; those who know him understand how much he has given back the other way.

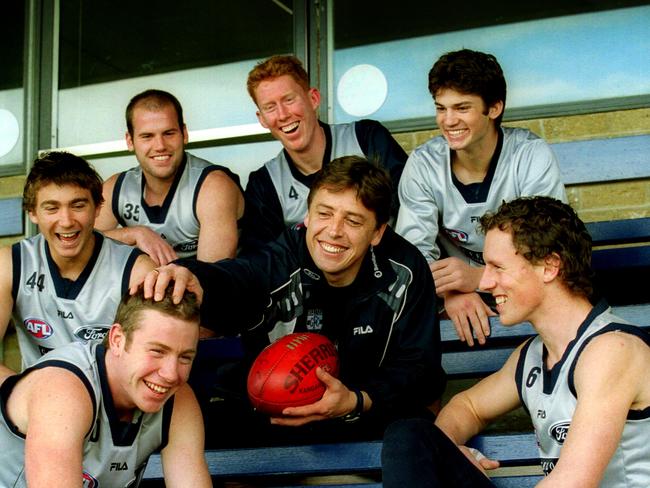

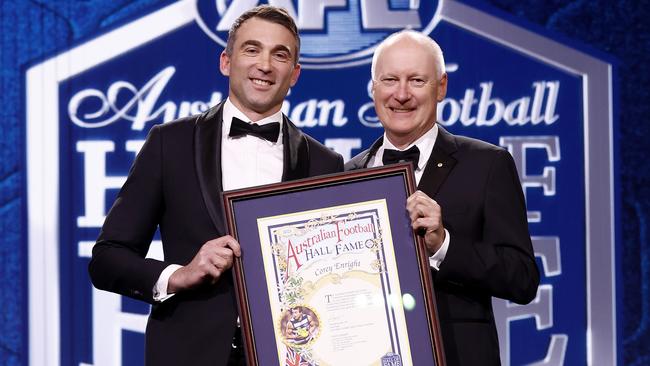

Enright: From sliding doors moments to a super career

– Scott Gullan

Corey Enright is shaking his head. He’s running through the sliding doors moments of his career and is surprised how many he’s coming up with.

“There are so many times it could have changed,” the Geelong champion says.

Where do you start?

The Enright story started in Kimba, a small country town with a population of around 600, five hours north west of Adelaide.

“There were no phones, no internet, no YouTube, no Netflix, I think we only just got Foxtel. We had nothing compared to what kids have now,” Enright explains.

“You’d go to school then after school you hang out and go and have a kick of the footy, play cricket or throw the basketball. Sometimes you’d go to someone’s farm to shoot a few rabbits.”

At 15 Enright was playing senior football for the Kimba Tigers who were zoned to Port Adelaide. He was invited down to Adelaide to tryout for the state U/18 team but got cut at the last minute.

“I was a bit cut, bit devo about that,” Enright says.

He was still doing his final year at the local school where there were five Year 12 students, three boys and two girls.

“Our footy coach was the science teacher so he would just let you go and do whatever, it was a beautiful way of growing up,” Enright recalls.

“I couldn’t do PE because no-one else wanted to do it. I ended up doing home economics with one of the girls where I learnt how to cook and got some life skills.

“For me (playing AFL) was never really on the radar. I was a knockabout lad playing country footy.”

In his draft year he was invited down to play in Port Adelaide’s U/19 team which was an adventure in itself.

“I would get on a plane, a 20-seater that morning, fly in, get picked up at the airport, play the game and that night go home or occasionally I would get there the night before and stay at one of the guys’ houses,” Enright said.

“It was a big effort. I then had a decision to make once I finished school. I didn’t have a farm or anything, we lived in the town so I was like I’ll go to Adelaide, someone will help me out, I’ll play down there and see what happens.”

Unbeknown to Enright Geelong had been watching his five U/19 games with Port Adelaide but not actually for him.

“I think Bomber (Thompson) was the one in the end. They were watching Daniel Foster who also got drafted and we were on the same team,” Enright says.

“He was from the country as well and played a bit more. They were watching the game on the tape and Bomber apparently said about me, ‘I like this kid’. Fortunately they had seven draft picks that year and I think they just threw a dart at the board.”

Enright was selected at No. 47 in the 1999 national draft but there was one minor issue, he knew nothing about Geelong.

“I hadn’t been to Victoria, I hadn’t been to Melbourne, I thought Geelong was a suburb of Melbourne,” he recalled.

“They put us up with a beautiful lady who lived at Bell Post Hill. I didn’t have a car or a phone for the first 12 months, I was just relying on people. I was a fish out of water, I had no idea.”

It was no surprise that he didn’t play a senior game in his first season and while he made his debut in Round 2, 2001, Enright was homesick to the point where his parents thought he was going to throw it in.

“I was just paddling for 12 months and they would have thought what the hell is this kid doing? Why did they draft this lad for?,” Enright says. “Mum and Dad came over and we met Bomber in a cafe in Essendon and he was like he can’t go home, he has to stay.

“I don’t know whether it was because he pushed for me and could see something in me when others couldn’t. He knew which buttons to push, he gave me games when I shouldn’t have and then made me work when I maybe should have been playing, just those little things that good coaches do.”

Enright played every game in 2003 before his career again veered off path. Over the next two seasons he missed large chunks of time courtesy of a broken jaw, broken wrist and a medial ligament injury.

He was away on the football trip at the end of 2004 when he faced yet another sliding doors moment. Enright was rooming with captain Steven King who kept having to leave the room to take phone calls which he thought was strange.

When he returned home the reason became clear. The Cats were trying to organise a trade with Richmond for ruckman Brad Ottens and Enright’s name had been mentioned as part of a possible deal.

“I was in and out of the team with injuries,” Enright recalls. “I got back and my manager said, ‘Do you want to go back to Port Adelaide?’ I was like, not really, but they were interested and the feeling was Geelong would probably do it as they needed a pick to help with the Otto deal.

“He said they don’t want to lose you but they need to get Ottens in. So had I said yes I think it probably may have happened. Fortunately for me I was contracted and I felt like I was starting to get my roots down in Geelong.

“Brent Moloney was the one who had to make way so again that was a sliding doors moment.”

By the time 2007 rolled around Enright had played 100 games, found his niche at halfback after starting his career as a half-forward/wingman and was growing in confidence by the week.

As he says the second half of his career was chalk and cheese compared to the first.

Three premierships, two best and fairests in premiership years (2009-2011), six All-Australian jumpers and a club games record of 332. (which would be later broken by Joel Selwood).

He also took ownership of the most underrated player in the competition tag which still even gets thrown around now about the new AFL Hall of Fame inductee.

“It probably had more to do with my persona and my personality than my footy,” he says. “We had some big personalities in the group who took a fair bit of the limelight so I was happy to be third or fourth fiddle.

“I always based myself internally, that was always my measure. I loved my teammates so much I didn’t want to let them down. I also respected the staff we had, they were the people who motivated and drove you to perform.”

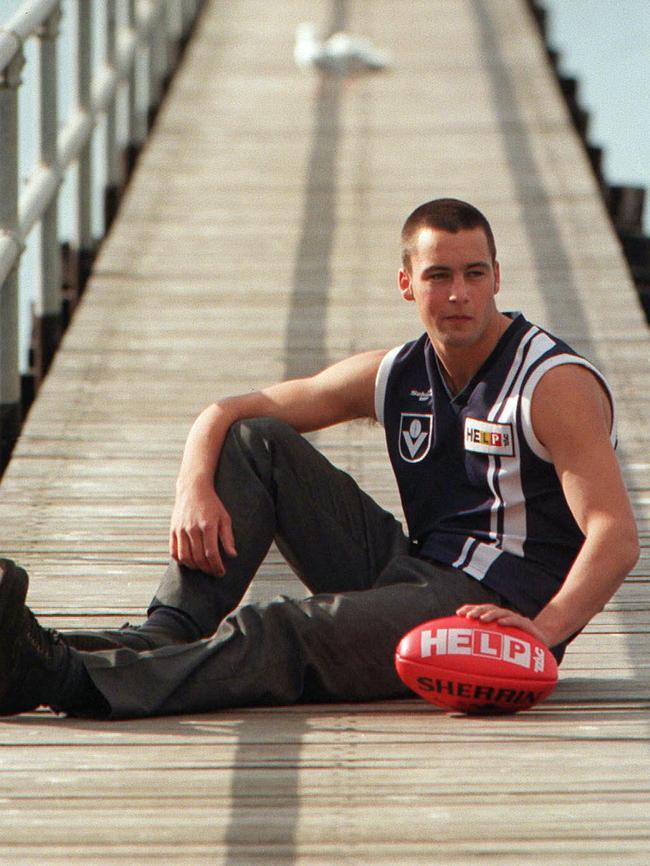

Bartel: The boots that started a storied career

– Scott Gullan

Jimmy Bartel still has them at home. Throughout his whole career he kept them close by in the boot-studder’s room at Kardinia Park.

His first pair of the Adidas black and white Copa Mundial boots hold a special place in the former Geelong superstar’s heart.

In 2001 the AFLPA began the Mike Fitzpatrick Scholarship which offered financial assistance to help young footballers chase their dreams and one of the first to be awarded one was a young ball magnet from Bell Park in Geelong.

At the time Bartel’s mother, Dianne, was working three jobs while running a house with three kids in it. She was a strong woman who didn’t want her children to go without but they understood the circumstances.

Football-mad Jimmy would regularly go down to the local op-shop and find a pair of used boots which were inevitably the wrong size but he just made it work.

“The problem was my boots kept flying off because they were too big so one of the Dad’s at Bell Park, he had an older son so he said I could take his old boots,” Bartel recalls.

“I was always getting hand-me-downs or going down to the op-shop.”

The scholarship changed things and Bartel proudly bought a new pair of Copa Mundial boots. Later that year he was drafted to Geelong at No. 8 in the national draft and started a journey which saw him become one of the most decorated footballers in AFL history.

And all through the 15 seasons at the Cats, those old boots were always in the next room, close by if he ever needed any inspiration.

“I could never let them go, they were special and a reminder of where I’d come from,” Bartel says.

There is no need for think music when Bartel is asked about career turning points. He fires back without hesitation – Round 2, 2004 Geelong v Carlton at Princes Park.

By this stage Bartel had shown a bit, playing 25 games in his first two years under coach Mark “Bomber” Thompson. But the Cats had a dirty day against the Blues, losing by 54 points to make it a 0-2 start to the season.

He remembers there were irate board members in the rooms afterwards. The pressure was on but he thought he was far from the worst player. However, when selection came the following Thursday he was the only player dropped.

Bartel went back to the reserves and played well, He kept churning out good numbers but suddenly Thompson wasn’t giving him any love.

This went on for two months.

“It was tough as you are a bit confused and you start thinking does he (Thompson) genuinely want me to be part of this club,” Bartel says.

Finally in Round 10 he was recalled against Port Adelaide in Adelaide but spent the whole first quarter on the bench.

“I was like, ‘Here we go, he doesn’t want to play me again’ but then someone had a blood rule or something at quarter-time so I got let loose and kicked a couple of goals.

“We then played the Bulldogs at the (Telstra) Dome and again I sat on the bench until someone came off hurt. That was the game I took that mark running back and I played really well for the rest of the game.

“I never went out of the side again.”

That mark saw Bartel run back at full speed and launch himself into a pack to take a courageous chest mark which was just as good as Nick Riewoldt’s much heralded mark at the SCG in the same year.

He went on to poll 13 votes in the 2004 Brownlow Medal – the most votes of any Geelong player – despite essentially missing the first half of the season.

This was a precursor to what was ahead for the No. 3 who had started to capture not only the umpire’s eye but also the rest of the competition.

His tough, uncompromising, fearless attack on the ball combined with rugged handsome looks had him a pin-up boy for many fans.

And as Geelong rose to power from 2007, Bartel was front and centre with his Brownlow Medal victory that year coming despite missing three games. The 23-year-old polled 29 votes to win by seven.

“I missed one game throughout the year when I got concussed and then got appendicitis so I missed the final two games,” Bartel said. “I knew I’d played pretty well throughout the year, I didn’t think I was going to win but I also didn’t want to get there and get pipped because my appendix burst.

“Fortunately the last game I played I got three votes and (assistant coach) Brendan McCartney had actually been nervous about that because we had someone go down and he asked if I could go to halfback. I said no worries and clearly played well enough for the rest of the game at halfback.”

He was back in the middle the following Saturday when the Cats piled on a record Grand Final winning margin on Port Adelaide to break the club’s 44-year premiership drought.

Two more flags followed in the next four years and in many ways each of those grand finals highlighted the true brilliance of Bartel, his flexibility and ability to play a number of different positions.

In 2007 he played midfield collecting 28 possessions and kicking two goals. In 2009 at quarter-time Thompson went straight to him and told him he had to tag a rampant St Kilda’s Lenny Hayes.

He sacrificed his game for the team, quietening Hayes and leading the Cats to a final quarter comeback and 12-point victory.

Then in 2011 against Collingwood Bartel moved to centre half-forward when James Podsiadly got injured in the second quarter. He proceeded to collect 26 disposals and kicked three goals which saw him awarded the Norm Smith Medal.

Only a handful of players have won the two biggest individual awards in the game but for Bartel his overwhelming feeling when thinking about his 305-game career is simply being “incredibly grateful and lucky”.

“I got picked by Geelong which was two blocks from my school, I got to the club with absolute perfect timing with the transition of Frank Costa, Brian Cook and Bomber Thompson,” he says.

“There were a couple of good drafts who all came through together and I had two coaches in 15 years, some guys have had two coaches in a year. Plus I was part of an environment just full of aggressive competitive characters who every single day were trying to get better.

“That’s a pretty special thing and it has an edge to it. Then from there you’re all just moving in this wave together.”

Bartel’s oldest son, Aston, has just started playing in U/10s and it’s helped the latest AFL Hall of Fame member to bring back those great memories from his own childhood.

“For me the best place to be as a kid was the footy club. Whatever is going on in the world, you go to the footy club and train, that’s your happy place. You can compartmentalise and shut off from the world for a while.”

St Kilda great Nick Riewoldt also qualified this year for elevation into the game’s Hall of Fame and has accepted the honour but will be feted next year given he is currently living in the United States with his family.