What I saw in the Boxing Day tsunami aftermath

We were looking for signs of hope, but when we arrived we saw more than a hundred bodies laying there in rows so their faces were visible to the disaster recovery experts buzzing around them, writes Sarah Blake.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Our cab driver was starting to repeat himself, frustrated that we didn’t seem to understand his reluctance to drive us to Khao Lak.

“You don’t want to go there — too many cops,” he said again.

It was December 28, 2004, and I had been in Thailand less than 12 hours with photographer Michael Perini, sent by News Corp Australia’s Sunday newspapers to cover the Boxing Day tsunami.

We hadn’t seen too much damage yet. It’s the job of a foreign correspondent to find your countrymen when disaster strikes overseas, so first stop on our arrival in Phuket had been Patong Beach’s Aussie Bar to rustle leads and stories about Australians.

We sat that morning and marvelled from the first floor as an army of bar girls and their families hammered and drilled and concreted in a furious attempt to right the destruction of the massive waves. The Indian Ocean had pushed back to destroy all but the standing structures for more than a hundred metres of infamous Patpong Rd.

At the end of the street, in a basement-level supermarket facing the beach, dozens of bodies remained in the water where they were trapped two days earlier.

In town near the hospital, walls of noticeboards were quickly thrown together, some showing photos of the dead, others fluttering with pinned up pictures of the missing. Families and survivors stood solving the grimmest puzzles in the hot morning sun.

Everyone said the worst lay north, 100km away in Khao Lak.

After convincing our driver we weren’t worried about “the cops”, that we were in fact looking for them because they might be able to tell us what was going on, we joined a convoy. Dozens of trucks passed us headed in the other direction, their flat bodies stacked high with the dead.

As we rounded one corner, a large fishing boat sat tilting to the side a couple of kilometres inland.

We crested a final hill and our upset driver almost spat us: “See, I told you, too many cops.”

He was pointing at a field leading to the beach. More than a hundred bodies lay there, most naked and burnt by two days in the sun and water. Almost all were on their backs, many twisted and broken and laid out in rows so their faces were visible to the disaster recovery experts buzzing around them. We realised our driver wasn’t worried about the police, rather all the corpses.

The United Nations, foreign embassies and Red Cross worked out of tents holding more of those tragic whiteboards.

Family members had started arriving from overseas and they stumbled from tent to tent in a fearful hunt for their loved ones. I will never forget the big, white-haired German man who stopped me, sweating and teary, holding a photo to my face of a beautiful young man.

“Have you seen my boy? My son, have you seen him?” he asked, a portrait of dread and grief.

After three weeks covering the aftermath in Thailand, as earthquakes and aftershocks continued to batter the worst-hit Aceh in Indonesia and the death toll there climbed, it was hard to uncover any stories of hope.

We were anxious to find some good news.

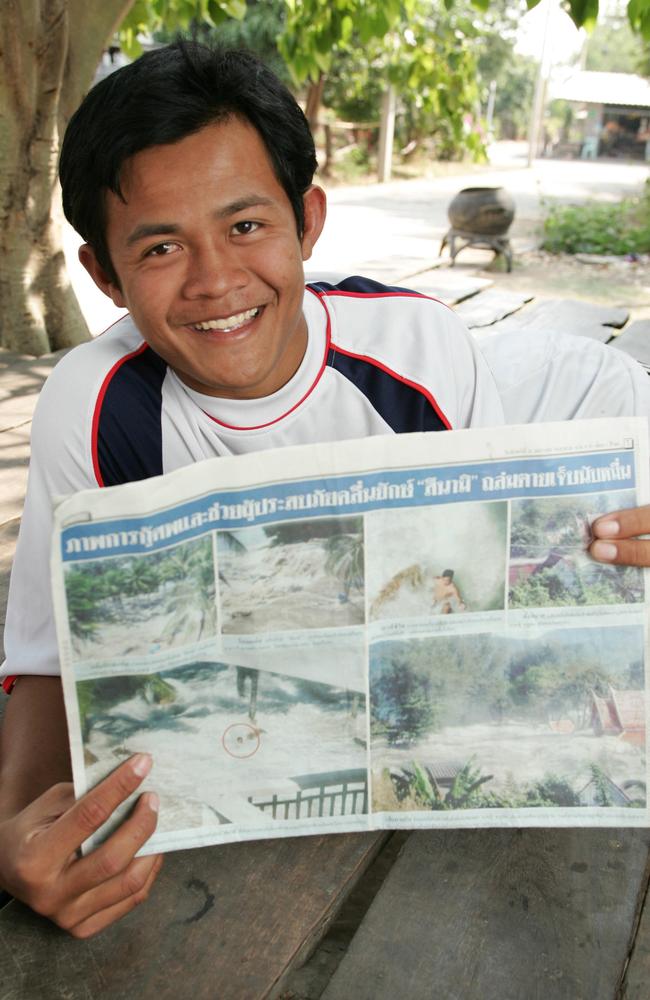

One of the first photos of the tsunami, an Agence-France Presse picture that had fronted newspapers across the world, showed the terrified face of a young Asian man being swept in a torrent past the tops of palm trees to what seemed like certain death — somewhere in Phuket.

We started to fixate on him. What was his story? Wouldn’t it be amazing if he survived?

The internet was a dimmish blip in early 2005, so overnight our pic editor in Sydney tracked down the photographer, a stringer who had headed to Hong Kong in January and was happy to sell us the rest of his original set of photos. We were faxed a proof sheet from his strip of negatives and in a couple of frames we could see a hotel with distinctive, white cookie-crust balconies on the beach.

We started showing these images to everyone we spoke to, and after a couple more days we had consensus that they were of a hotel at Karon.

Walking the beach there and asking locals if they recognised the face in the water, we finally found someone who knew our man: he was a food vendor from somewhere near Bangkok named Yai. He was alive, but had gone home. One of his friends spoke passable English and was happy to take us to his home and work for a fee as our fixer, translator and driver.

The next day we flew to Bangkok, then drove 350km west to Yai’s home in a little rural village.

Nobody there could really understand why we had turned up to talk Yai, but they welcomed us. He was shy and uncomfortable with the attention, but agreed to pose for some photos with his sister and tell us about his memories of December 26.

He described a normal morning, busy with the rush of tourists there for Christmas, and the quite sudden arrival of the waves. He believed he would die as he was swept along, and somehow grabbed on to a palm tree as he passed — probably not long after he was photographed — and waited there as the water subsided. He had no explanation for his survival when so many had died, but said he would lead a good life from that point in the hope he could honour those lost.

Yai’s story ran across all of our front pages and was followed up by dozens of international titles, all of them keen, as we were, to show something positive, some kind of good news out of the unimaginable horror of a natural disaster that claimed 280,000 lives.

Yai’s story remains one of the most important of more than 20 years I have spent reporting the news. What job could be better than being charged to tell the stories of those who are struck by history? But the most indelible image of resilience I took from those weeks in Thailand was of those Patpong Rd business owners, too busy to stop their trade, determined to clamber and work so hard to rebuild what nature tried, and failed, to take from them.