Ukraine conflict reveals five new things about Vladimir Putin

He has charmed and disturbed world leaders for decades but the conflict in Ukraine has exposed five things we didn’t know about Vladimir Putin.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

During his decades in power, Vladimir Putin has both charmed and disturbed world leaders all the while giving very little away on how he saw the future for himself and his nation.

But his war with Ukraine – now in its fourth month – has changed that and has taught the world five new things about the diminutive Russian president that provides a bleak future for him and the rest of the world.

1. POWER

There would have been little doubt to anybody who has followed a G7, G20 or any global leader’s forum what the Russian leader was thinking. It followed a Russia First principle that he exuded with characteristic national fervour. Everything in Russia was bigger, better, stronger he would say and was perhaps how he saw himself personally (but more on that later). In some quarters he was viewed as a humble quiet achiever who inherited glasnost and was looking to leverage new found ties with the West, including active courting by some Western leaders, for the betterment of his beloved nation, still mighty but needing friends.

Certainly the contracts his State-linked energy companies negotiated with individual European Union nations was testament to that. And yes there was the Putin association with and influence over the then US President Donald Trump, which US analysts are still attempting to unravel.

But with his invasion we now know his perceived nationalistic passion goes further than simple patriotism and masks a personal desire to reshape the world for the ages, in his mould. He has never made a secret of his loathing for former Soviet leaders including Boris Yeltsin, for whose office he worked, when they pushed glasnost, the policy of consultative governance and openness. He had long considered that to be a weakness of State and while seemingly giving the allusion of a Kremlin seeking to be more open with its people and Western democracies in fact he was shifting the opposite way.

This has never been more telling in the way he personally, and through him the rest of the Moscow politburo, has spun his invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation”. His televised address hours before the February 24 invasion spoke of this and it was accepted. As the bodies of Russian military soldiers piled up it was Putin again that decreed any other view portrayed, disseminated or broadcast would be contrary to hastily arranged laws and punishable with a decade in jail.

Putin has previously with glistened eye talked about the golden age of the Soviet Union before it collapsed under the weight of a corrupted Kremlin and economy but before February no-one seriously believed he would attempt to recreate the Soviet Union, one state at a time starting with Ukraine. Yes he conquered the Crimea in 2014 with barely a bullet fired but that was more complicated and was largely ignored by the West. By 2015 he was openly making aggressive overtones toward Ukraine but even in places like Germany there were protesters with placards demonising the bully West in favour of Putin.

Non-resident Fellow of the Lowy Institute and Russian expert Bobo Lo said the invasion was never about NATO or Ukraine’s membership but simply about a man who believed he was smarter and stronger than anyone else.

“For him, better a disorder where Russia is central than an order in which it is a secondary player. Power, not problem-solving, is the consuming priority,” he says.

Unlike with successive Chinese premiers content with playing the long game over generations before expressing their desire for world domination, Putin perhaps realised he no longer had time on his hands.

2. HEALTH

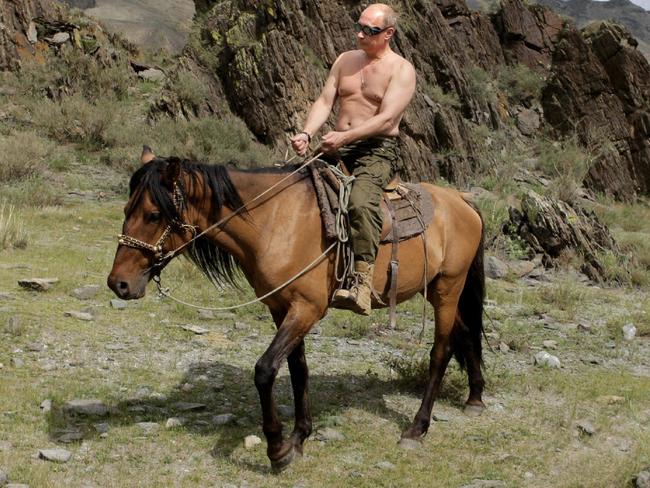

Rumours of his ill health have circulated for years and were furthered only by his desire to be seen as the strongman in staged photo opportunities with him in judo tussles or riding bare-chested in the wilderness while out hunting, shooting or fishing. Such was the persistence of rumour, the Kremlin issued a statement to deny ill health. But with the invasion he was having to be seen virtually daily to appease a rattled domestic supporter as well as international leaders.

In the beginning he seemed strong, at least in his conviction, but as the war has dragged on it has clearly taken its toll on his health. As late as this week a Russian FSB intelligence officer who defected to the UK claimed the 69-year-old only had three years to live with a rapidly progressing cancer. He has been seen shaking uncontrollably and his television appearances are apparently edited to remove signs of perceived weakness. There has been speculation too he has been suffering from Parkinson’s disease. With meetings with among others French president Emmanuel Macron to talk about a treaty with Ukraine, observers noted he appeared twitchy and ill at ease beyond the subject matter. There have also been reports out of the Kremlin of wild mood swings and uncontrollable temper flares as well as failing eye sight. Former billionaire oligarchs, stripped of their wealth by Western sanctions, have spoken about a blood disorder that needs around the clock medical attention but perhaps that’s wishful thinking.

Then there’s his mental health. The former head of M16 Sir Richard Dearlove has said Putin could be out of office by year’s end and in a sanatorium. Certainly Putin had not envisaged what struggles he would have with Ukraine nor the response by the West that is now seeing Russia collapse in economic quagmire and this would have to have taken a mental toll.

“I think [Putin] will be gone by 2023 – but probably into the sanatorium, from which he will not emerge as the leader of Russia,” he said. “I’m not saying he won’t emerge from the sanatorium, but he won’t emerge as the leader of Russia any longer. That’s a way to sort of move things on without a coup.”

When the FSB issued an internal directive to regional chiefs not to believe his reported “terminal medical condition” it had the opposite effect. This was only bolstered during the Victory parade earlier this month when in a relatively mild 9 degrees he coughed and spluttered his way through proceedings and was the only one that required a blanket over the knees for the cold.

3. FRIENDS

The list here is small and dwindling rapidly, with even ally Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko showing some reluctance in doing the Kremlin’s bidding even when Russian troops were being routed and his help was sought on the Ukraine border.

Various other former Soviet states that had courted Russia to varying degrees were now not wanting to be on the wrong side of history. No-one except perhaps China, Iran, Syria and North Korea. The Kremlin’s active courting of these rogue states shows how far the country has slipped that it openly wants to join the arc in autocracy and in so doing boost trade, notably in weapons and energy. China last week went as far as conducting joint bomber drills in the disputed territories about the South China Sea. Begs for the adage about my enemy’s enemy being my friend.

4. INFLUENCE

This is surprising but in many respects Putin has bolstered domestic support with a clear majority backing him and his invasion. But then, the true extent of his quest has not been fully outlined domestically and many believe it is a military operation to put down a Nazi movement in Ukraine, as Putin and the Kremlin have told the public. His approval rating according to pro-government pollsters VTSIOM and FOM is up to 83 per cent. He has successfully shaped the Russian psyche. Perhaps many doubt what they are being told but still believe he is doing the right thing. Not only has he shut down any dissenting voices in government and mainstream media but he has curbed the influence and power of outside social media domestically to be replaced by his own trolls.

“Many Russians want to believe what they are being told – especially by Putin, their contemporary vozhd (all-powerful leader) – perhaps subconsciously conforming with the historical characterisation of how the authorities were purportedly viewed in imperial Russia: ‘good Tsar, bad courtiers’,” retired New Zealand diplomat and analyst Ian Hill said.

Staged supporter rallies aside, Putin does remain popular with the people and within Kremlin.

One of Ukraine’s leading commentators and vice rector of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Lviv, Myroslav Marynovych, said Ukraine is bleeding but Russia is dying and there was national guilt in the latter.

“In 1944 all Germans supported Hitler but in 1948, in the 1950s the whole nation passed through a catharsis so this is the future of Russian nation. They are not ready now for catharsis, only few of them, but I’m sure in the process of the transformation of the world Russia will pass through it.”

5. VULNERABILITIES

The war has shown Putin to not be the economic reformer many considered. He was propelled by then Soviet leader Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s off the back of Russia’s economic collapse on the belief he was a market reformer and understood the importance of a diversified and connected economy. But he is not and he has clung to a centralised and monopolised economy revolving around energy (oil and gas), the consequences of which are now exposed by war and crippling sanctions. The war has also shown his military may not be as mighty as once thought. He has frequently touted Russia’s military strength with hypersonic missiles and the advanced Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missiles but his forces have lacked co-ordination in logistics, communications and smarts in forward planning. His military may have so far been decimated by a minnow (albeit backed by militaries of the West) but Russia remains a nuclear power and if he is sick, mad or set to be overthrown leaves the world in a dangerous place.