New terror war Australia can’t stop as Russia-Ukraine war creates hacktivists using video games

Intelligence agencies say the Russia-Ukraine war has indirectly created two cyber crime streams that extend to Australia where no laws exist that could stop hackers from establishing an ISIS-style terror phenomena.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Russia-Ukraine war is indirectly creating social and political hacktivists using online video games and cyber hacks that risks creating an ISIS-style terror phenomena.

Intelligence agencies have noted two parallel cyber “themes of concern” emerging from the conflict, both of which extend to Australia which has no clear laws to combat.

One is the apparent ease in which online gaming sites involving the most popular platforms can be exploited for espionage, radicalisation or dissemination of messages.

This was potentially networking like-minded future extremists and criminals across the world.

The other was the more overt cyber warfare campaigns being directed by State recruited largely volunteer “armies” now involved on all sides of the war being armed with cyber tech skill sets they can potentially offer for hire.

According to a commissioned report passed to Australian and Five Eyes intelligence agencies from UK counterparts, the “gamification” of the conflict and romanticising cyber attacks could have consequences.

Already the war had attracted unprecedented cyber attacks including on Australian infrastructure and the defence supply chain by Russia hacking groups including Killnet, suspected of working for Russian intelligence.

Ukraine’s much vaunted “IT Army” of volunteer cyber hackers had blurred the distinction between combatants and civilians given they were trained by the State but free to work anywhere.

“In the past, countries have had to deal with civilians leaving and joining terrorist organisations, becoming radicalised and then returning to their native countries,” a report commissioned by UK’s National Cyber Security Centre released this month points out.

“Many governments have developed systems to deal with this potential threat. With cyber operations, however, an actor can conduct attacks at a distance.”

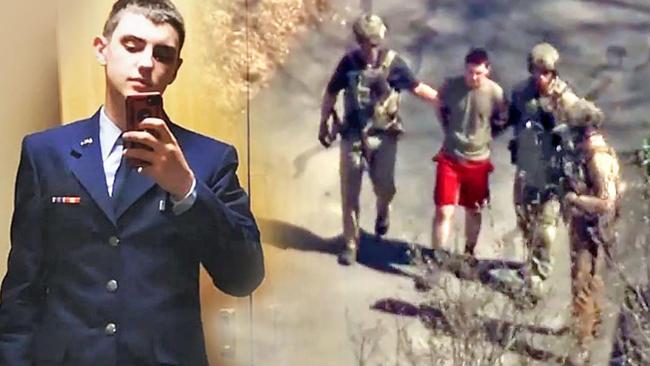

On the games front, US Air National guard Jack Teixeira embarrassed the Pentagon and its allies after he leaked highly classified details about the Ukraine-Russia conflict on a gaming chat group as the Russian Kremlin-linked Wagner private mercenary army attempts to spread disinformation including attempts to infiltrate popular video game Minecraft.

Russian foreign intelligence services are also suspected to be using AI-generated girlfriends to now cyber target through gaming chat rooms lonely analysts for possible recruitment.

Ben Gestier, former intelligence officer for the ADF and AFP now senior analyst and team leader for risk intelligence group Flashpoint, said pro-Kremlin hacktivist groups had become more open.

“For example Killnet briefly rebranded as a ‘private military hacking company’, the Phoenix group started selling data and accesses, and other groups sought co-operation with cyber criminal gangs and darknet forums,” he said.

“Some of the groups have been linked to Russian security services which may also be a financial motivation for them … it is plausible for these hacktivist groups to act as hired cyber guns, especially if animosity between Russia and the West persists, as is likely, or as allies of more sophisticated State-backed groups determine where ‘red lines’ lie.”

The Australian Signals Directorate Director-General Rachel Noble said the war took agencies from cyber hypotheticals to actual in terms of private sector businesses and individuals on mass entering the war as cyber operators.

“For organisations like ASD, that makes that whole environment very messy and it can be very difficult to discern whether it’s a State-based actor, a criminal, a criminal operating at the direction of the State-based actor, or just deriving their own intent from that State actor and then undertaking offensive action. It’s really messy.”

THIS IS NO LONGER A GAME

Two weeks ago Finland’s largest selling media daily Helsingin Sanomat creatively hid newspaper articles inside one of the world’s most popular shooter online video games Counter-Strike: Global Offensive.

The newspaper built a map inside the game of a war-torn city called “De-voyna”, after the Russian word for war, where players are led to a secret room of images and Russian text on the cruelties as witnessed by its real life news teams in Ukraine during the war, now in its second year.

The move was designed to get around Russia’s restrictions on foreign media in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine and local ban on describing the conflict as a “war”.

“If some young men in Russia, just because of this game, happen to think for a couple of seconds what is going on in Ukraine then it’s worth it,” editor-in-chief Antero Mukka said of the novel counter censorship approach.

The move was not criminal nor necessarily sinister but highlights how the war in Ukraine and technology is reshaping online warfare and reaching global audiences that security agencies now fear could lead to broader real world harm.

Intelligence agencies have noted two parallel themes of concern emerging from the conflict both of which extend to Australia which has no clear laws to combat.

One is the apparent ease in which online gaming sites involving the most popular platforms can be exploited for espionage, radicalisation or dissemination of messages, potentially networking like-minded future extremists or criminals.

The other is the more overt cyberwarfare campaigns being directed by State recruited “armies” now involved in the Russian-Ukraine war, that has led to unprecedented cyber attacks and left unchecked Five Eyes intelligence agencies have warned could become as potent a threat as terrorism.

The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre commissioned a report into the cyber aspect of the Ukraine-Russia war that this month identified “concerning precedents” and a blurring of lines between combatants and civilians.

There was Russia’s Killnet hacking group, identified as making cyber assaults on critical infrastructure against Ukraine and the West including in Australia and Ukraine’s IT Army, a volunteer network of hackers that has been engaged in cyberwarfare with Russia since the conflict began.

Both had “gamified” the conflict by romanticising the cyber fight, notably the IT Army with authorities providing step-by-step outlines on how to target and achieve effects and questions what will happen after the actual war ends or their interest ends and the hacktivists move on.

“In the past, countries have had to deal with civilians leaving and joining terrorist organisations, becoming radicalised, and then returning to their native countries,” a report released this month points out.

“Many governments have developed systems to deal with this potential threat. With cyber operations, however, an actor can conduct attacks at a distance.”

It added, drawing tech savvy volunteers in to fight for the State was simpler than radicalisation and no country had an existing legal framework to deal with the issue.

There was also a blur between political hacktivists and those interested in financial gain.

Ben Gestier, former intelligence officer for the ADF and AFP now senior analyst and team leader for risk intelligence group Flashpoint, said pro-Kremlin hacktivist groups had become more open.

“For example Killnet briefly rebranded as a ‘private military hacking company’, the Phoenix group started selling data and accesses, and other groups sought co-operation with cybercriminal gangs and darknet forums,” he said.

“Some of the groups have been linked to Russian security services which may also be a financial motivation for them … it is plausible for these hacktivist groups to act as hired cyber guns, especially if animosity between Russia and the West persists, as is likely, or as allies of more sophisticated State-backed groups determine where ‘red lines’ lie.”

Dr Brenton Cooper, CEO and co-founder at Adelaide-headquartered open-source intelligence company Fivecast, said FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt) had become a viable objective for State actor-led cyber operations.

“We’ve seen the power of these paramilitary groups loom over the West for some time, but today’s mounting global conflict potential certainly deepens the threat. Deniable proxies – private contractors – are being played out to manipulate Western democracies in increasingly sophisticated ways. And with the internet and its influence almost infinite, the challenge for national security teams now is stitching together a holistic intelligence picture.”

Equally concerning has been how extremists are exploiting gaming platforms, now designed as customisable and as a social communication space, to recruit and spread ideology.

US Air National guard Jack Teixeira embarrassed the Pentagon and its allies after he leaked highly classified details about the Ukraine-Russia conflict which he shared with a gaming social chat group, not for espionage purposes but for kudos with gun-loving gaming peers on the Discord platform.

It is the same platform the Russian Kremlin-linked Wagner private mercenary army uses to spread disinformation as they have tried to infiltrate popular game Minecraft. Russian foreign intelligence services are also using AI-generated girlfriends to cyber target through gaming chat rooms lonely analysts for possible intelligence.

“The relative ease with which extremists have been able to manipulate gaming spaces points to the need for urgent action by industry actors to avoid further harm,” a cyber hack and gaming report from the New York University Stern School of Business this week concluded.

The connection of contemporary gaming to radicalisation and violent right wing or other extremism had already been linked to real-world violence notably in the US.

Steven Stone, who heads data security company Rubrik’s data threat unit exposing espionage-led assaults, said geopolitical events often inspire groups sympathetic to regimes standing in opposition to them, notably Five Eyes nations (US, UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand).

He said all cyber actions should not be viewed as separate from malware attacks or other technical activities for profit or intelligence gain notably by Russia, China, Iran and North Korea.

“In essence, it is all part of a spectrum of activity that often overlaps,” he said.