'We heard a whoomph . . . a drum flew in the air'

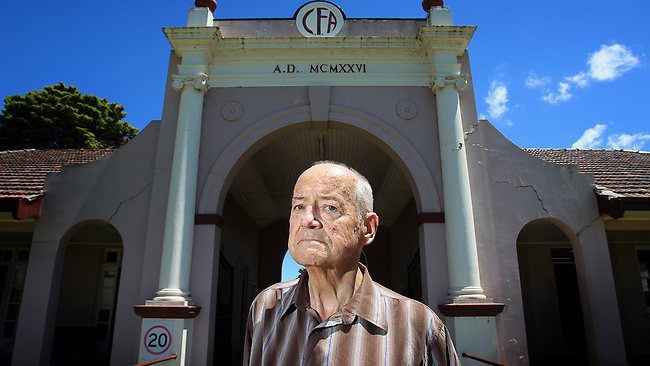

BRIAN Potter wants to know why his beloved CFA didn't warn anyone about chemicals at Fiskville that could be making people sick.

PAUL Potter spent his wonder years at Fiskville. There were acres to tear around on his Dragstar pushbike. No strangers to worry about. No cars to dodge.

Almost every day thick smoke belched from the burning chemical pools where the latest batch of CFA recruits were in training.

Those black clouds darkened the sun in the afternoon. The kids would leave the schoolhouse and stare at the big burns. They'd breathe it all in as they crowded round. Moths to a flame.

Their mums would whip the clean shirts from the Hills hoists. They'd bounce their little ones in their prams down the gravel road to get closer to the fire and the smoke. To watch their men walking blind into the thick of it.

These were CFA families. The training burns were part of life. The stash of acrid wooden pallets that the kids would turn into cubby houses was part of the Fiskville landscape. So were the 150 slow-leaking, unmarked, corroded drums piled two high in the centre of the 180ha property.

The kids would pass them on their walk to school, sometimes climb up the top and jump off.

The dump, way out the back, was off limits, so Paul and his mates always went there. Of course they did - they were kids.

They'd kick the dirt, jump their bikes over half-buried barrels and gunk that no disposal companies would touch. These were the late 1970s, early '80s. Innocent times. No one knew what they were burning. No one knew what the kids were mucking around with. No one knew they were playing with more than just fire.

BRIAN Potter got his life insurance policy paid out in 1999. He was so sick he wasn't expected to last long. His diseases could have killed him 15 years ago.

Paul has watched his dad's suffering. This man, who pledged his loyalty to the CFA as its Chief Officer, now fights for life. Doctors slice away cancers and give him drugs to buy him time.

Brian's last child of four married this year. He's hanging on for them to have children, because he doesn't want to go before he's met all his grandkids. And he doesn't want to leave his wife, he adds. They're still in love after all these years.

He met Diane on her 17th birthday. He was 24.

"'I was the oldest of nine, and she was the youngest of three. At first, I thought she was a spoiled brat," Brian laughs.

They married a few years later. They had wedding photos taken in front of the Colac fire truck.

Diane sometimes feels like she's losing him. How much can one man take? A serious and rare auto-immune condition (Wegener's disease). A stroke. Bladder cancer. Bowel cancer. Secondary cancer in his liver. Bladder cancer again. Will it end? Will his funeral be the next?

Over the years, there have been lots of funerals. One after the other, good CFA friends from Fiskville have died too young. Many of them were in their 50s. Brian's lucky. He's made it to 68.

He gives good eulogies. He has had lots of practice. They ask him because he knew many at Fiskville like family - as chief instructor he didn't just run the place, he was mentor and mediator.

It was a time when brigades in Victoria were lucky to have a firetruck and the people were their most precious resource. To Brian now it feels like a bygone time.

He knows nine from Fiskville who have died - cancers, brain tumours, heart failure, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, multiple myeloma. There are probably more he doesn't know about. He wonders why the CFA isn't helping them and their families.

He firmly believes he is sick because of things he touched and breathed in at Fiskville.

Others the Herald Sun has contacted wonder, too. Some don't want to know. They want to remember their dear departed without a black cloud. They say there's comfort believing it was nature that took them early.

For every person who's died, at least the same have suffered from similar diseases and survived.

"Either it's the greatest coincidence of all time, or there was something at Fiskville that has made us sick. It's an awful thing for us to know now these illnesses were gnawing away at us without anyone understanding," Brian says.

He and Diane live now with their daughter's family. The never-ending medical treatment has drained their pockets and their strength.

But mostly, Brian worries about all the good men, women and children in Fiskville at that time. Some of them wouldn't know they're at risk. They should tell their doctors, get tested, so they can catch problems before it's too late.

Lived or trained at Fiskville? Let us know your experiences. Email Ruth Lamperd at lamperdr@heraldsun.com.au

Kaye Maguire wishes her husband's brain tumour was picked up earlier. By the time they found it, it had wrapped around his optic nerve.

They couldn't remove it all. It took 10 months to kill him in 2003. Gavin was an instructor at Fiskville with Brian.

"We loved our years at Fiskville. It felt like good money. We could do everything we wanted. I've got everything now that I could want ... except Gavin," Kaye says tearfully.

Brian's suspicions grew late. He heard early this year how many New York firefighters had fallen to cancer after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Back home, Brian remembered there was a report hidden deep in CFA headquarters detailing some of the chemicals handled carelessly at Fiskville. He had heard rumours that something dangerous was contained in those drums.

A few months ago, he called a senior member of the CFA and told him his fears. They picked a morning and made a time to meet a week or two later.

"They have a duty of care to him. And to everyone else that may be affected," Diane says.

But the CFA man didn't show up. Brian hasn't heard another word from CFA headquarters.

BRIAN and his loyal CFA friends would never say this, but some firefighters in the 1970s and 80s wore their red underpants on the outside. There was a Superman complex. The culture was macho, para-military. For those, a fire hose was the next best thing to a gun.

They'd walk head-on into thick, toxic smoke. They couldn't see beyond their plastic visors.

The CFA was cash-strapped. The Arab Oil Crisis in the mid '70s had pushed up fuel costs. Volunteers needed to learn, but Fiskville CFA management didn't want expensive petrol to go up in smoke.

Each time the pits would light up they'd pour in 200 litres of fuel. It would sometimes burn three to four times a day. That would amount to $2000 a week. It was a lot of money in the 1970s.

So CFA workers would scour Victoria for combustible waste. There was plenty of that stuff. Burning pad supervisor Ken Lee remembers taking out the Fiskville tanker and sucking up the sludge from the bottom of service station tanks, collecting old fish-n-chip shop oil, air force waste and paint and petrochemical factory left-overs.

It was the worst of the worst gunk. Everyone in the business knew Fiskville was a willing dumping ground.

Ken was pad supervisor for 20 years from 1979. He had a pretty good idea what the materials were, but not what it could do.

He remembers chemical companies dropping semitrailer loads near the pad. He'd roll the drums off the truck. When a burn was imminent, he'd open up the bungs and the liquid would run out.

"The stuff we burnt in those days was well and truly bad news. Today you wouldn't even go near the drum it's in. A lot of people have suffered ... It's awful to think I was responsible for all that stuff. I just didn't know. Nobody knew it was dangerous," Ken says.

Sometimes when the bungs were opened, the contents were so thick they wouldn't flow. Two semi-loads, in particular, were like that.

The chemicals were shifted and stored along a central roadside in the middle of the settlement. Those drums were stacked two high.

They were the ones the kids jumped from, passed by on the way home from school. There was a rotten egg smell around them. They stayed there for years, rusting and leaking.

ALAN Bennett was an unlikely fit for the CFA. He once grew a beard against protocol. When he thought something, he'd say it straight and clean up later.

People loved his gruffness, because behind his straight face and blunt words he was smiling. Alan was an instructor at Fiskville when Brian was there. He was highly regarded, despite the beard and the attitude. Maybe because of it.

He struck health problems before he left Fiskville. Benign tumours were cut from his nostrils.

He suffered chronic dizziness and deafness. When he left Fiskville the problems just got worse but his specialists were stumped. They wanted to know what the chemicals were.

In his Bendigo dining room last month, Alan flicks through an old file of letters and documents. He nearly shredded them last year, but something stopped him.

Now, he's glad he didn't.

Alan is the only one from those early Fiskville years to have a CFA-commissioned report into the contents of those corroding drums. Hardly anybody has seen it. Getting the CFA to give him the information was a battle.

In December 1982, Alan and CFA colleague Don Pink needed more flammable material for a burn, so they decided to test what was in that stash of containers. It didn't go well. They moved a drum aside and tipped some of the liquid on the ground. Some drums had split open and they could see a bitumen-like substance, another a clear, fuel-like substance and another a mixture of the two.

They lit the stuff. They waited. Nothing happened. Alan can picture Don standing there with his hands in his pockets, thinking it was inert.

They turned and walked off, wondering what was next. Then, when they were a dozen steps, away the thing went up.

"We heard a whoomph. We turned around and a drum flew 20m into the air," Alan recalls.

The men prepared reports into the 1982 incident and filed them with their bosses.

"I had always been healthy, but after that I couldn't find the door out of my office. I just didn't know what was going on. I thought I'd had some sort of nervous breakdown," Alan says.

The CFA - including Brian Potter, who was a deputy chief at that time - decided those drums needed to go. No disposal companies would take them so they prepared to have them buried. Henry Hume was a contract front-end loader operator and often did the dirty work at Fiskville. He dug a hole near the rubbish tip in the far back of the property - the forbidden place where Paul Potter and his mates played.

Henry didn't like the look of them. Some of the drums were cracked and empty. Alan clearly remembers Henry's hesitation - there was no careful placement of the drums in the hole, but quick dumping and covering up.

"Henry told me after he got sick years later: 'If I'd known what was in those drums, I'd never have touched them'," Alan recalls. Henry died two years ago on New Year's Eve on the dance floor, of a massive heart attack they think. He'd had cancer before and had only 25 per cent hearing. He was married to Coralee for 46 years and eight months. Their daughter survived two benign brain tumours, discovered and removed years later. She was a student at the Fiskville school from prep to year 6.

Some of the drums Henry buried are believed to be next to the CFA's adjoining airstrip. The Herald Sun believes a tractor dug some of them up a few years ago when they were planting trees.

"You can see where the drums were," says an unnamed Fiskville worker two weeks ago. "They're under the spot where the trees won't grow properly."

ALAN still has the CFA report into the toxic chemicals in a three-ring file. He takes it out and counts the pages - 32 of them - and holds them up: "That's what I can't show you."

When he left the service and got paid out $3000 he promised only to show his doctors. The money had covered some of his medical expenses and legal bills. (He'd needed a lawyer's help to get answers after he became sick.)

But Alan promises he'll tell all under oath in court if he has to. The guilt eats away at him. He wonders if he could have made a difference. He wonders whether earlier diagnoses could have saved more lives.

What he knew was dynamite. A letter to him from the CFA human resources manager in August 1990 stated: "It was concluded that the principle contaminant at the site consisted of aromatic compounds ie. resins or solvents and may include Benzene, Toluene, Zylene and Phenol."

These were early days, but Alan knew the dangers these compounds posed to human health. So did the CFA.

He insisted on a full copy of the report and, in October 1990 - more than two years after he first asked for substance tests - the CFA handed it over.

But in the letter accompanying the report the CFA manager wrote the information should be "treated in confidence by yourself, to be used solely for the information of your specialist".

For Alan the report was cold comfort. He knew these chemicals were potentially disastrous. He wrote to the CFA a month later saying: "In previous discussions ... I expressed the opinion that, should there be the likelihood of a health risk from the buried deposits, there were others involved who I felt should warrant advice along with myself. I was told that should samples be taken, advice would be distributed. I do feel that this should be done."

And in October 1991 he wrote again: "As you are aware, the consequences of these chemicals activating at any time in the future, and the damage they may cause concerns me greatly."

No one was told. Most of the drums were eventually dug up and disposed of properly. But the report stayed buried.

The Herald Sun contacted families of more than 15 people who suffered serious illness or died since the 1990s, but none were ever told what they were exposed to.

Tony LaMontagne at Melbourne University's school of population health is cautious, as scientists should be.

Proving an individual is sick because of a chemical exposure is difficult in the scientific and legal world. And apparent spikes in illnesses can sometimes never be proved to be more than a statistical blip.

"But whether the exposure is related to the disease or not, people experiencing this have added anxiety that they were misled or not informed. That can cause as much pain as the disease itself.

"There is a duty of care to tell people. It's the right thing to do. We can never sort these things out if we don't talk to each other and get over the legal liability mania."

It weighs heavily on Alan's mind now. He expected the CFA would do the right thing by their people.

"These people are my friends. The CFA was obliged to let them know what was there. But I shouldn't have assumed they would," he says.

"I paid off some of my legal and medical bills with the small amount the CFA gave me, signed a form declaring the CFA wasn't negligent and gave my word that I wouldn't say what was in the report," he says. "Then I ran like a rabbit."

PAUL Potter is angry. He feels like a ticking time-bomb. Those carefree days at Fiskville were perilous. If only they'd known. The CFA should have told them when the information surfaced. Good people had a right to know.

He remembers the sacrifices his family made for the CFA. The biggest was their father, who dedicated his life's work to the Silent Service. That's what people called it. Silent service. CFA men gave unwavering loyalty.

One night when the Potter kids were young - pick any year - it was six days since they'd seen dad. Or was it seven? Diane was like a parson's wife. She'd pick up gracefully where her husband left off. In earlier days she'd broadcast the nightly regional reports over the two-way radio because her husband was out at some function or fire.

When days without Brian stretched on, Diane would line up their four young children on the couch at night. "OK kids, let's watch dad on the telly," she'd announce.

The new Beta VCR would be switched on and they'd play footage of Brian - by now the CFA Chief Officer. Every time his head popped on to the TV screen the last few fire seasons Diane had taped him. There was enough now for a mini-documentary.

If they couldn't have him here, at least they could watch him.

He was ambitious and stoic. The Potters were shifted around Victoria without question. When career officers retired, they kept the faith still. They joined up as volunteers. They helped where they could. Duty first. And don't ask questions later.

Brian and his firefighting friends came from that willing era of silent service. Even now it's uncomfortable for him to speak a word against the CFA which he loves.

But he figures he's beaten the odds and stayed alive for a reason.

That's why he's speaking out now. For the good people of Fiskville. Before the silence kills him.