Troy Cassar-Daley’s heartfelt letter to his son and why he has ‘no regrets’ about smacks

In this incredibly moving letter to his son Clay, Troy Cassar-Daley has opened up about the type of father he’d hoped he’d be and the one he became.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dear Clay,

I always wanted to be a father, ever since I was a boy. I always dreamed of being a good dad, just like my father was to me.

When I was young, I would hold my little cousins, who were a few years younger than me, and think about how I wanted to hold my own little child like that one day.

I think these feelings stemmed from the fact that I didn’t have a lot of continuous time with my own father, because my mum and dad broke up when I was 12 months old.

My goal even as a child was to fix what I felt was broken about my own childhood and be there 24/7 with my kids.

When I met your mother, I knew she was the one from the minute I spoke to her.

She was gorgeous and smart, and we made each other laugh, and laughter is very important to me; it always has been. I fell in love with your mum straight away.

Your mother and I had our own careers, but we were very much on each other’s side as soon as we met.

When we first got together, I was taken back to the dreams from my childhood of being a father one day.

But I also realised I wanted to be a good husband too. I’d always hoped I’d find someone who was willing to work alongside me in an equal partnership in life; not to be a housewife but to follow her own career as well.

Your mother was that kind of woman. She was driven, compassionate and we had each other’s back all the way. Growing up with my mum, who was a single parent, I always had huge admiration for strong women. I was surrounded by them because my aunties were strong as well.

When your mother came along, I could tell that she was also strong and resilient. Saying what we meant to each other made my heart sing, and we bonded from that moment on.

After your mother and I got married, we’d often look at each other and say, ‘What are our kids going to look like?’

‘If they look anything like you, they will be gorgeous!’ I’d say to her. And I was right, you and your sister are gorgeous.

I would also say to my wife that we can’t have only one kid. I was an only child and it was terribly lonely a lot of the time. After we had you, Clay, there was quite a gap before your sister came along. I kept nagging my wife, saying please don’t let this little fella be an only child.

When you came into this world, in my mind I turned back into being a child again, saying to myself that my dreams will come true. And they did.

I held you and thought, I get to be a father now and be responsible for a little human life. This was something I took more seriously than anything in my life before, because I knew that I was about to help shape someone else’s life. I wanted to always be there, to see it through.

As well as my dad, I had other male role models when I was growing up. They were in my Aboriginal family, starting with my grandfather, Henry Daley, and my uncles, Gerry Daley, Buddy Daley and Freddy French.

These men filled the gaps left by a broken family and gave me the tools to be who I am today, from teaching me to fish, how to hunt for witchetty grubs, and ways to fix a car or bike. They were always there to talk through problems I was having.

All the things they showed me about being a father were in my heart the day I first held you when you were born. I couldn’t wait to show you all the things that made my life rich – culture, love, humility and the value of family.

Being a musician and working at night, I had the luxury of doing school drop-offs. Some parents dropped off their kids then drove to work.

But I wanted to be more involved in your morning drop-off, so I started to play handball with you and all your mates before school.

For most kids it would not be cool to have a grown man – your dad – playing handball with you and your friends, but you accepted me. I’ve since had some of those kids, who are now in their early 20s, come up to me and say, ‘I remember playing handball against you when you came to school with Clay, and they were some of the best games we ever had with no cheating!’ Those words mean so much to me.

Words and actions can break the cycles that are hard for us in our lives.

As I look back at the role models I had who helped me to break these cycles, they make me think about the role model I want to be for you and your sister. Henry David Daley, my grandfather, was a railway worker and a proud Indigenous man who only thought about providing for his family.

He had nine kids and he was able to rent an Aboriginal Commission home for all 11 of them. Eventually he got a loan to buy it, and he paid it off the week he retired.

He broke a cycle of having to depend on others, and broke many stereotypes that were around for Aboriginal men of his generation.

I remember Pop as a quiet man.

He passed away when I was nine and he was quite sick toward the end of his life. His mother died early in his life and he was raised by a few different relations. My mum recounted a story about Pop while he was working on the NSW Railways.

One of his colleagues accused him of stealing pumpkins that were growing wild by the track near the railway yards at South Grafton. The man said something to this effect: ‘Typical thieving Blacks, taking those pumpkins.’

Well, my Pop heard this comment and proceeded to walk over and punch this bloke in the jaw. Then he said, ‘I didn’t lay a hand on any bloody pumpkins, thank you.’ And he went right back to work.

Those attitudes were rife in his day. I think Pop wanted to prove people such as this man wrong by fitting in and working bloody hard.

It would have been tough for all his generation, but he didn’t wear the hardship like a badge. Instead, he just slowly changed people’s minds. I used to get a huge thrill when someone would say to me, ‘My father used to work with your Pop on the railways and he said he was a great bloke and a great worker’.

On the way through your early life, Clay, I worked on helping you to understand that humility, tolerance and accepting people as they are is important to making you the best human being you can be.

When you were little, I encouraged you to share with your sister and your first cousins and not be cheeky to your mum or me.

You and your sister got a smack when you were naughty, just like I did as a kid. I have no regrets about that because from a very early age you learnt right from wrong, and you’ve never forgotten it. If I did something wrong, I’d get a smack from Nan or Pop, from my mum or from my uncles or aunties.

No one was immune from being pulled into line in our big extended family. It was all about respect – you disrespect someone, you get a smack.

You were always an old soul; my mum and aunties said you had been here before. Your sister Jem, on the other hand, was carefree; a little solemn at times but usually she doesn’t have a care in the world. She’s the best little sister you could ask for.

I’m so proud of the people you and Jem have become.

Your mother and I look at you both and shake our heads and say how lucky are we to have two grounded, humble and compassionate kids who have grown into caring adults.

Now you are living in your own unit with a mate, and you have a steady girlfriend who is wonderful.

I hope you’ve seen the respect I have for your mum and it makes its way down the generation into your relationships.

There is no such thing as a perfect relationship. If someone says they’ve got through life without a bump in the road, they’re kidding themselves.

I’m proud to say we are still here as a family, still respecting, loving and caring for each other whenever we need it, and that’s probably the most important thing. We cherish having each other in our lives.

Clay, fatherhood is a beautiful commitment that will never leave me until they put me to rest. I am so happy and proud to be dad to you and your sister. Dad.

Troy Cassar-Daley

Gumbaynggirr, Bundjalung

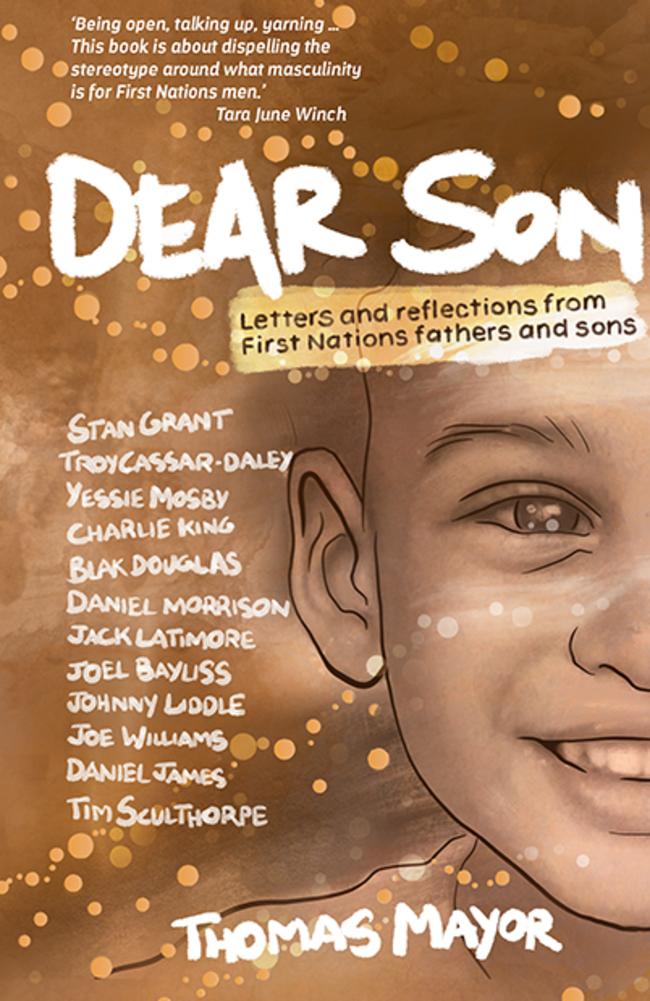

This is an edited extract from Dear Son: Letters and reflections from First Nations fathers and sons, edited by Thomas Mayor, Hardie Grant Explore, $35

More Coverage

The smart way to keep up to date with your Courier-Mail news

Originally published as Troy Cassar-Daley’s heartfelt letter to his son and why he has ‘no regrets’ about smacks