Babylon’s ancient clay tablets made more census than today’s computers

THOUSANDS of years ago the only hackers of census data were the scribes employed to inscribe the clay tablets to record the information.

IN Babylon in about 3800BC a team of men headed out to tally up the numbers of men, women, children, livestock, slaves, butter, milk, honey and vegetables in the kingdom. The primary reason was to figure out how much food was needed to feed the population, but the figures also gave an idea of how many men were available for military service and how much they could be taxed without starving them.

The team went on foot or by horse and cart, recording data on clay tablets. Unfortunately none of the raw data survives today — the Babylonians probably sent the tablets through the equivalent of clay shredders to make sure their privacy was protected!

The Babylonians probably used a simple system of people visiting households and counting them in person. It was a system seemingly less prone to problems than that used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics this week: no hackers (other than scribes smudging the clay) or crashes (the potential for a horse and cart to roll over and spill the tablets), yet they still managed to deliver a reasonably accurate picture of how much food the kingdom needed.

Other kings tried to improve on this simple system. In his Histories Book IV, the 5th century BC Greek historian Herodotus mentions a Scythian king (from what is today part of Iran) named Ariantas who wanted to know how many people he had in his kingdom. Rather than bothering with scribes to knock up forms, he simply commanded all of his people to bring him a bronze arrowhead. The penalty for noncompliance was death, so Ariantas ended up with a huge pile of arrowheads. Once he had counted them (Herodotus doesn’t tell us the exact number) he had the arrowheads melted down and made into a cauldron as a memorial to his census.

There is also a story that the mythical first king and founder of Athens, Cecrops, held a census in 1582BC. Again he didn’t bother with forms or other messy systems. He simply commanded his people to drop a stone on a heap, presumably in the centre of his city then set the stone counters to work collating the data. It came to the nice round figure of 20,000.

The ancient Romans set new standard for people counting. In the 6th century BC king Servius Tullius created the post of Censor, a magistrate responsible for overseeing Roman morality and collecting population statistics. Taking the census in ancient Rome was a complicated process. Firstly the call had to go out to all the dwellings in Rome that a census was to occur on a given date. All Roman citizens (slaves excluded) had to turn up to the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) military parade ground and, after the auspices were read to make sure the gods were pleased, register their name with the head of the Roman tribe (traditional divisions of the Roman population) to which they belonged. The head of the tribe recorded how wealthy the person was, where his family came from and how much property they owned, among other things.

Although being registered meant a citizen could be taxed or called up for military service, there was an incentive for those who registered would also receive benefits such as a free ration of grain. As the empire grew more people were enrolled as citizens and censuses taken. Although due to the size of the Roman Empire at the time, these were held less frequently.

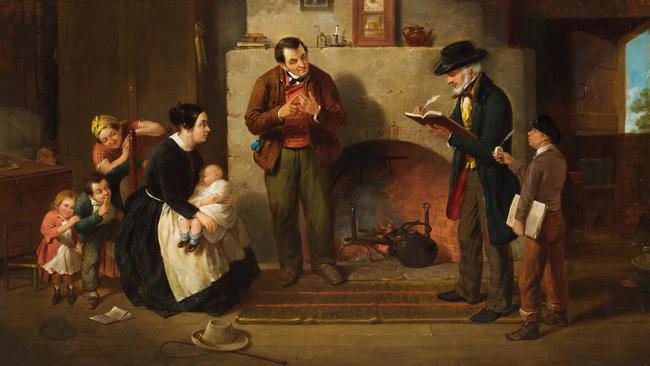

William the Conqueror employed an army of men to collect the data for his record that would become known as the Domesday Book. To make sure that no one fudged the figures he sent people to check the work of the first team and any discrepancies resulted in severe punishments.

Sweden overcame dishonesty in census returns in 1749 by getting the clergy to compile population statistics based on the list of parishioners they had long regularly kept.

The US held its first census in 1790, when US marshals and their deputies visited every house. The British held their first census in 1801, with official census takers filling out standard forms.

The first census in Australia was conducted in NSW in 1828, it excluded indigenous people and was made more difficult to collect by the fact that some colonists lived miles from civilisation.

This was still a problem when people had to travel for days to collect data from far-flung settlers during the 1881 great census of the entire British Empire.

There is also a story that the mythical first king and founder of Athens, Cecrops, held a census in 1582BC. Again he didn’t bother with forms or other messy systems. He simply commanded his people to drop a stone on to a heap, presumably in the centre of his city so that he could get the stone counters to work on collating the data. It came to the nice round figure of 20,000.

The people who set the standards for head counting were the ancient Romans. In the 6th century BC king Servius Tullius created the post of Censor, a magistrate responsible for overseeing Roman morality and collecting population statistics. Taking the census in ancient Rome was a complicated process. Firstly the call had to go out to all the dwellings in Rome that a census was to occur on a given date. All Roman citizens (slaves were excluded) had to turn up to the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) military parade ground and, after the auspices were read to make sure the gods were pleased, register their name with the head of the Roman tribe (traditional divisions of the Roman population) to which they belonged. The head of the tribe recorded how wealthy the person was, where his family came from and how much property they owned, among other things.

Originally published as Babylon’s ancient clay tablets made more census than today’s computers