Frank Manley reflects on night of Tasman Bridge collapse and that iconic image of his teetering Holden Monaro

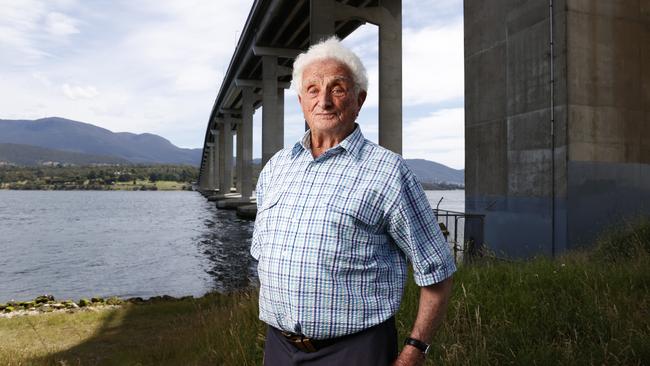

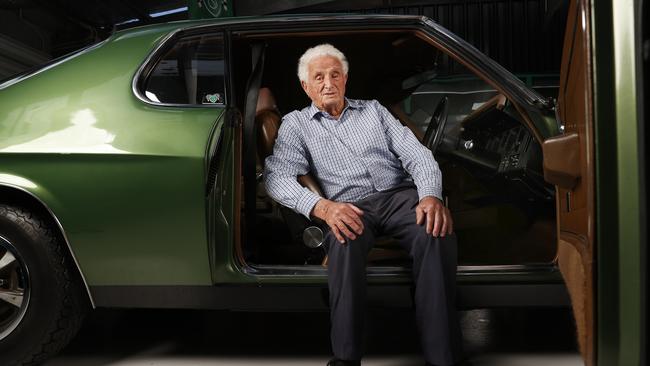

Cambridge resident Frank Manley has reflected on the night of the Tasman Bridge collapse, recalling how he managed to survive the disaster even as his now-famous car teetered over the abyss.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Frank Manley still remembers the night of January 5, 1975 like it was yesterday.

It was a drizzly evening in Hobart and a foreboding gloom hung over the city.

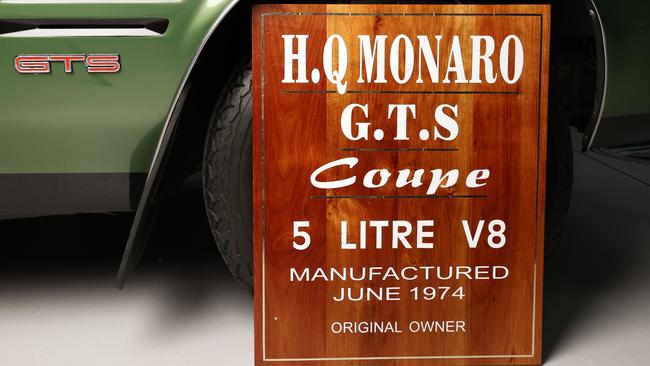

Mr Manley, who is now 94, was driving over the Tasman Bridge in his 1974 Holden Monaro GTS, with his wife, daughter, and brother-in-law as passengers.

Bound for the Eastern Shore, he realised in the nick of time that a void had opened up ahead of him – where the bridge had been, there was now nothing but a sheer, dizzying drop.

“I spotted the white line missing and I hit the brakes. I said, ‘I can’t stop. I can’t stop. I can’t stop’,” Mr Manley told the Mercury.

“Anyhow, we did stop. Then we swung over [the edge of the bridge], and the wife said, ‘Put her in reverse’. I said, ‘Bugger reverse – bloody well get out’.”

It was 9.27pm – although Manley swears it was earlier – when the SS Lake Illawarra struck the bridge, causing it to collapse.

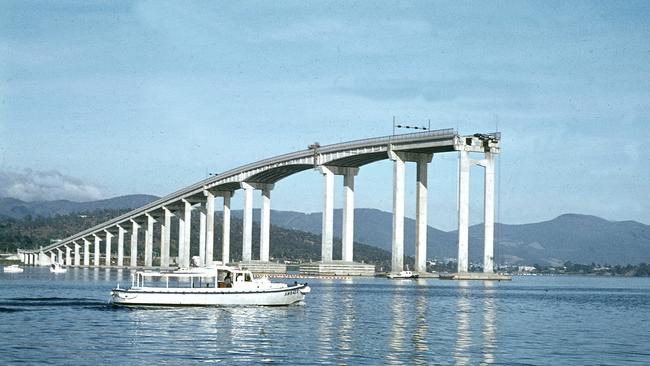

Perhaps the most iconic image to come out of the Tasman Bridge disaster shows Mr Manley’s green Monaro alongside Murray Ling’s Holden EK wagon, both delicately poised on the edge of the collapsed bridge, threatening to plunge into the River Derwent below.

Mr Manley said as soon as he and his family had leapt out of the car, they sprung to action, desperately trying to alert approaching motorists of the mortal danger they were in.

He paid tribute to his daughter, Sharon, in particular, who he said was just 16 at the time and joined him in shouting and waving at cars in a bid to stop them from unwittingly driving off the bridge.

Mr Manley said about two hours elapsed before he was escorted home to Cambridge with his loved ones.

“We didn’t know the ship had hit it until later on that night,” he said.

Then employed by the Public Works Department, Mr Manley was helping to build a highway in Southern Tasmania in the wake of the bridge disaster when he met then Premier Bill Neilson.

“He came around wondering how we were going with the new road. And he said, ‘You’re the bloke who was hanging off the bridge’. I said, ‘Yeah, I haven’t got a bloody razoo’. I lost a week’s pay and didn’t have the car for a few days,” Mr Manley said.

“[The Premier] said, ‘Have you got any receipts?’ I said I had the bill from Motors. And he said, ‘Bring it in’.

“A couple of weeks later, I got $200 back.”

Mr Manley’s Monaro now resides in the National Automobile Museum of Australia in Launceston and is part of the family trust.

He had only owned it for about three months when he had his brush with fate on the bridge.

Mr Manley said it was likely he would have sold the car eventually, had it not become inextricably linked to such a historic event.

“I used to always buy a new car about every three years. I would use it to go to work … I never, ever bought a second-hand one,” he said.

Mr Manley’s Monaro is the centrepiece of a display at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery as part of its On the Edge exhibition this month, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Tasman Bridge disaster.

As a moment of reflection for the lives lost, the Tasman Bridge will be closed for three minutes, from 9:27pm to 9:30pm on Sunday. Feature lighting will be dimmed to dark blue between piers 17 and 19 from 9:27pm to 9:57pm to signify the area of impact.

‘You could still feel the bridge moving’

Former Mercury Day Editor Ross Gates was a 25-year-old reporter for the paper covering the Tasmanian Tennis Open on the night the bridge went down.

“I was just finishing up my second story when we started getting reports that something had happened at the Tasman Bridge,” he recalled.

“Chief of Staff Malcolm Williams had sent the night reporter Ross Game out to see what had happened. After not hearing from Game, he asked me to go out to the bridge and let him know what was happening. There were no mobile phones in 1975 but we did have a car with a two-way radio.

Mr Gates said the bridge lights were out so he parked the car near Government House and ran past a policeman standing on the bridge.

“I remember that you could still feel the bridge moving,” he said.

“When I ran over the crest I was shocked to see a span had gone and two cars were hanging over the edge.

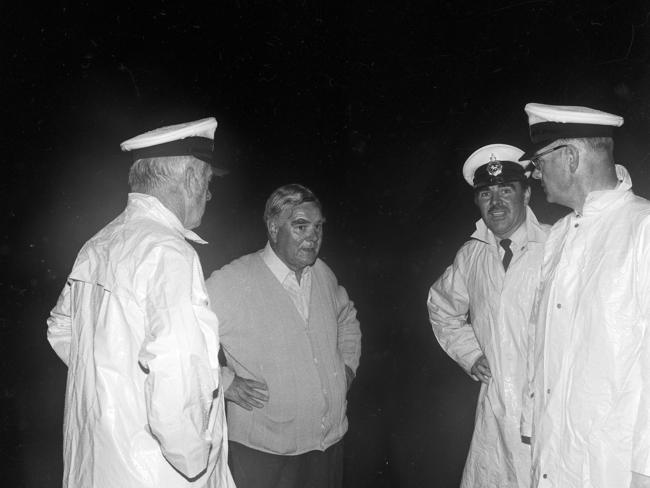

“Ross Game was talking to the driver of one of the cars, Murray Ling, and so I grabbed the other driver, Frank Manley.

“We could hear people in the water under the bridge as boats were picking up survivors.

“I started talking to Frank but the bridge was still moving and he was worried that it might collapse and wanted to get off it.

“So I was interviewing him as we jogged down the bridge. I had to remember what he said because I couldn’t take notes while we were running.”

Mr Gates said he also remembers an official party coming up the bridge as they were running off it.

“Among them was the Premier Eric Reece who was walking up with a few police officers.”

Mr Gates said when he reached the car he phoned Mal Williams to tell him what had happened, and of course the paper was changed for the story.

Mr Gates later went to the police station to get an overall picture of the disaster and had a list of the missing and injured crew members – but relatives still hadn’t been informed so the paper held off from publishing those details.

By talking to other reporters who had been sent to the waterfront, he estimated that a dozen people may have died, which turned out to be spot on.

Mr Gates, 75, said the bridge disaster was obviously an event he would never forget.

“It was probably the biggest story I’ve ever covered. It was a late night,” he said.

- PHILIP YOUNG

Up and down in a snap for historic shots

When the Tasman Bridge collapsed, Mercury staff were among the first on the scene.

Famed news photographer Barry Winburn’s images from that fateful night are part of Tasmanian history.

Interviewed about it years later, he was matter-of-fact about an astonishing night’s work.

But in a long career with many highlights, it was something he long remembered and spoke of often.

Leigh Winburn – who followed in his father’s footsteps to become the newspaper’s chief photographer – says early reports of the bridge collapse crackled over police radio, alerting the paper to the unfolding disaster.

Barry Winburn and reporter Ross Gates were among the first to rush the scene.

“Dad and Ross Gates got up [to the top of] the bridge before the police,” he said

“Dad often said it was pitch black dark because the lights were out.

“He was very much shoot [photos] first, worry about the consequences later.

“As they were going up the ship was settling in the mud and the sediment at the bottom and the whole bridge was shaking – and then the road just stopped and he was staring into the abyss.

“He got up there and was just completely aghast as he looked at these two cars hanging off.”

Barry Winburn worked fast, operating the old Mamiya C30 medium format camera press photographers used at the time – with only a dozen shots on a roll of black and white film.

“He wouldn’t have shot any more than 12 shots, because reloading the camera in the dark would have been a nightmare,” Leigh Winburn said.

Job done, Mr Winburn didn’t hang about on the still-shaking structure.

“He dashed back down the bridge, he was very glad to get off it too,” he said.

“He said he was exhausted getting up there, he wasn’t the fittest, but he came down twice as fast as he went up.”

-DAVID KILLICK

More Coverage

Originally published as Frank Manley reflects on night of Tasman Bridge collapse and that iconic image of his teetering Holden Monaro