Despite rumblings of mutiny Morrison endures rough sea

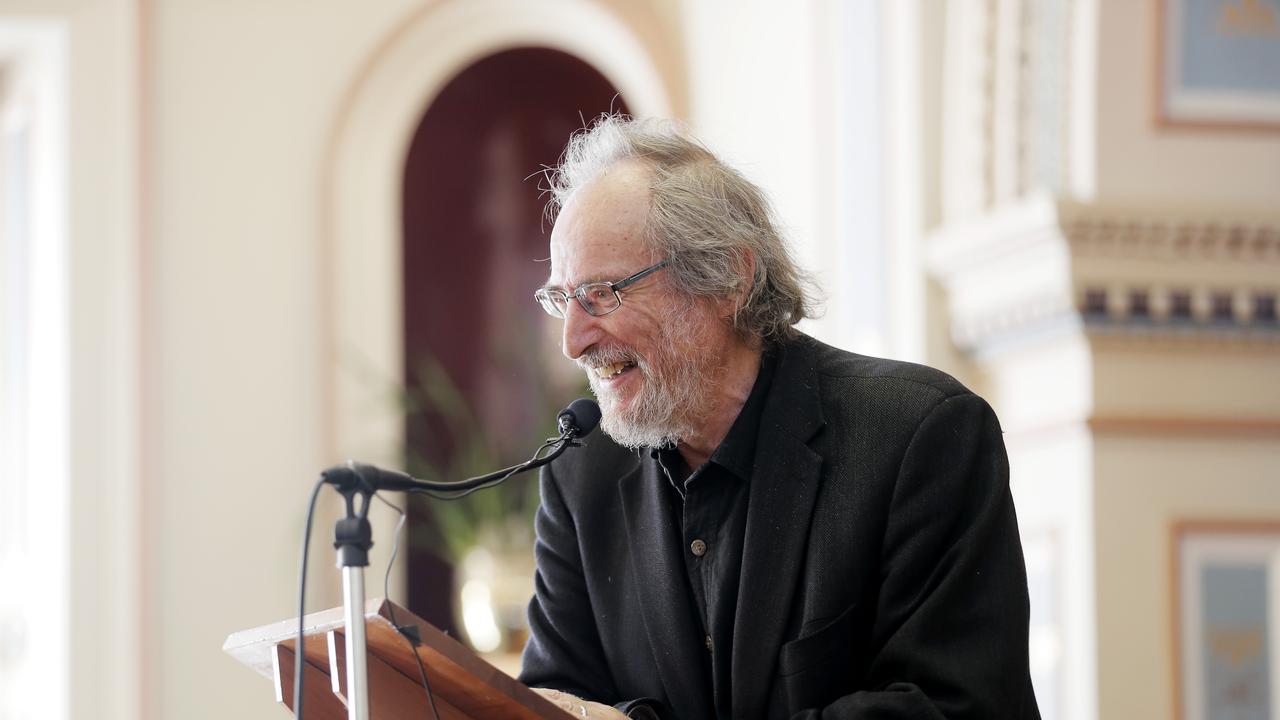

Even though ScoMo has taken a huge hit in the polls – they aren’t always reliable – so his plan to believe in miracles and tough it out, while hardly a strategy, will do until a strategy turns up, writes Charles Wooley.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

According to last week’s Newspoll, Scott Morrison has taken a huge hit ahead of the looming federal election, giving Labor a winning margin of 56-44 on a two-party-preferred basis.

Many previous prime ministers have polled so much better at this stage in the political cycle even while delivering far worse economic outcomes.

This Prime Minister has been cut no slack.

Few of our leaders have had to perform in times of such sustained difficulty. Even though he was in Hawaii for some of it, ScoMo led Australia through the disastrous bushfires of the summer of 2020, even if he didn’t “hold the hose” (which his critics have never forgotten) then he had to weather the floods of 2021 and, worse, two years of pandemic.

Fire, flood and plague are traditionally portents that the gods are displeased, but none of that worries a pragmatic and nervous party backbench half as much as shitty polling so close to an election.

When the political ship is sinking, loyalty always goes out the port hole along with the rats.

In the old days, they might have tossed the skipper overboard too, but in recent times that hasn’t worked so well. Instability can favour your opponent.

So, despite rumblings of mutiny, will ScoMo be left the dubious honour of going down with the ship?

The most likely leadership contender, the boatswain Peter Dutton, has just pledged his loyalty to his captain in much the same way as ScoMo once pledged loyalty to his skipper, Malcolm Turnbull.

So, who knows?

Politics is a cruel business. Suddenly you are on the nose and there’s nothing you can do about it.

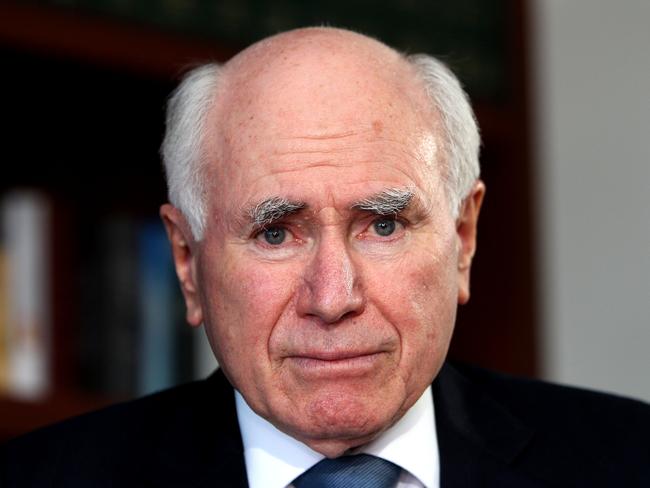

Look at John Howard, the most successful and longest serving Liberal PM since Menzies. He was swept from office in 2007 by Kevin Rudd with whom Australia soon fell out of love as did his party.

Howard had lost 23 seats and was so comprehensively trounced he even lost his own seat. That was a feat achieved only one other time in Australian political history.

During the “Kevin 07” election I was travelling with John Howard whose political antenna was always unfailingly sensitive. He knew he was losing but fought on bravely despite being on a hiding to nothing.

Much later I asked him what went wrong?

He told me, “People just thought we had been in for long enough and the truth is, no matter what I said, the mob just wasn’t listening.”

It feels like it is happening again. A big low has swept in. The wind has changed. The seas are rising. Captain ScoMo’s ship is leaking badly (to the media at least) and is battling hard to windward, right into the storm.

Meanwhile, his rival in this two-boat race, Captain Albo, has filled his sails and is on an easy downwind run.

The Opposition Leader doesn’t even have to shout above the storm. The less he says the better.

Albo announced some policies last week. I can’t remember what they were, and I bet neither can you.

Like Beazley back in August 2001, Albo looks dead set on course for the Lodge, so long as he doesn’t collide with another Tampa. (If you haven’t heard about that, kiddies, that’s all for the best. It was a shameful episode in Australian history which we should all be happier not to remember).

With an election due some Saturday between now and the end of May, anything could happen yet. The polls are an accurate snapshot of what people are thinking now, but they can’t predict future events and that is why ScoMo’s plan to believe in miracles and tough it out for as long as possible, while hardly a strategy, will do until a strategy turns up.

The PM had to eat his own words for lunch last week, admitting that in these tough times he didn’t always get things right. Most startling was his confession to the Canberra Press Club lunch that he had underestimated the potency of Omicron and its power to disrupt business as usual.

Then, a little later and out of the blue on Perth’s radio 6PR he told Western Australians that their Premier was quite right to keep their borders closed.

What?

Well, of course, it was a coded message only those sandgropers in vital but shaky federal liberal seats were supposed to hear. Between the lines, read, “Western Australians can vote Liberal in the federal election and we won’t force you to open your borders if you don’t want to. Promise.”

Pity the Prime Minister hadn’t given the same advice to Peter Gutwein a few weeks back. We wouldn’t have to shovel even more millions of your money into compensating the powerful travel and hospitality lobby for all the damage caused by our premier doing exactly what that industry so emphatically told him to do.

Generous grants for commercial self-harm hardly sounds like genuine conservative policy and in the long term is probably not even the best way of looking after your mates. We do live in strange political times.

Australia has one of the lowest pandemic rates in the world and accordingly one of the best performing economies in the OECD. Unemployment is at a record low as are interest rates and China’s bullying attempt to destroy our economic success has backfired spectacularly.

In an ideal world, where it was all about the economy, and not about Grace Tame, sports rorts, religious discrimination legislation, French submarines, rapid antigen tests, disloyalty and too many salacious scandals, then ScoMo’s electoral travails would scarcely exist.

But what has changed is that the old American maxim about the whole of politics, “It’s the economy, stupid”, now in itself looks stupid.

In an age of government compulsive big spending, when deficits don’t seem to matter anymore, fiscal responsibility has few supporters anywhere in politics.

And forget all the old slogans. The time-honoured mantra that “the Liberals are the party of business and what’s best for business is best for Australia” might now actually be dragging down the fortunes of the conservative side of politics.

Opening borders with so little knowledge of the mutant variability of what Trump called “The China Virus” was a clear signal for many voters that the Liberals are indeed the party of business but not the party of ordinary people.

And no amount of neocon-trickle-down-economics will wash with an electorate worried about granny getting Covid.

Even at his most unctuous, ScoMo can’t quite bring himself to say, “We can’t keep the borders shut forever but I’m really sorry about your granny.”

He will have to work on that one.

Given the disgraceful state of Australian nursing homes as revealed in October 2020 by the Aged Care Royal Commission, I would recommend that adman ScoMo frames a television commercial along these lines:

“Australia. We needed to open up.

“Sorry about granny.

“But she’s in a much better place now.”

Glady Berejiklian’s and Barnaby Joyce’s accurate assessments of the PM’s character were made public this week.

I have had dealings with every Prime Minister since Gough and would have thought those comments could’ve equally applied to any and all of them.

“A horrible, horrible, person … more concerned with politics than people.” Yes, Gladys, and your point is?

Then there was Barnaby calling the PM “a hypocrite” and “a liar”.

But hang on, Barnaby. Isn’t that part of the job description you are quoting there?

Fancy the post yourself?

It is going to be a long campaign. Enjoy.

Is it a case of missing or just sorely missed?

FROM time-to-time newspapers, including this one, run features on missing people. Stories of men and women who apparently vanish “into thin air” as the gravelly doom-laden voice of a TV promo reader might announce.

Whether TV or newspapers, editors have always loved a missing person story. The mystery of someone falling off the planet for no apparent reason fascinates readers and viewers alike.

As my old 60 Minutes executive producer, John Westacott would say, “Mate you can interview the Prime Minister if you must, but what the mob really want is a shark attack, a funnel-web spider story, or the yarn about an ordinary punter who has mysteriously done a bunk.”

In my early days on 60 Minutes, sharks, funnel-webs and people who vanished were guaranteed to sell Toyotas. And while deadly attacks by killer sharks and funnel-webs are rare, there is no shortage of people who go missing — the Australian Institute of Criminology says about 30,000 each year, equating to one reported missing every 18 minutes.

As my old boss would say, “Mate, the families always want to talk. It’s compelling television because it makes the viewer on the sofa even cast a wary eye over their own family and wonder who might be next.”

Most of the 30,000 reported missing return home to cuddles and kisses and, you might imagine, reprimands in equal measure — But about 1500 never return.

The figures have scarcely changed over the decades and if the missing were still alive, by now they might number the combined population of Burnie and Devonport, both fine cities in which to disappear.

There is a terrible sadness at the heart of missing person stories. While it is improbable the missing ones are alive and enjoying life in Rio, or anywhere else, it is also statistically unlikely that so many could be murdered, abducted by aliens or fallen into a time warp.

Unfortunately, among the missing there has always been a proportion suffering from psychiatric illness. Police presume many die by their own hand.

As a reporter it’s a heart-breaking story to tell. The families of the missing hope against hope, clutching at any straw of evidence. Sometimes their loved one has been sighted in an airport or a railway station.

When police are sceptical the family might even hire a private investigator, or fly interstate to check for themselves. In my experience the families share an abiding conviction that the police are not doing enough.

But talking to coppers, for whom the situation is always stressful and emotional, I’m told “unfortunately there is nothing left to be done” — the worst thing for a family to hear.

In 2013 covering a missing person story in Victoria, I met Snr Sgt Ronald Iddles, then a 25-year veteran detective of Victorian homicide and missing persons investigations. Ron Iddles whose conviction rate was 99 per cent was often called “Australia’s greatest detective”. But for all his years in serious crime, Ron was not hardened to the suffering of the families of those missing.

“It’s not a crime to deliberately go missing,” he told me. “But when it comes to the next of kin, an inexplicably vanished loved one causes as much pain and suffering as you would find in the worst crimes.

“Worse maybe because of the uncertainty, the not knowing, and the inability to accept that they are most probably dead. And more likely dead by suicide than by misadventure. It is too much to bear so they deny it.”

So powerful is their state of denial that even with evidence of psychiatric illness and depression, families often refuse to accept the truth. “It is understandable,” Ron said. “You can’t tell people what they don’t want to hear. And if you do, they just think you’re not looking hard enough.”

The remains of the missing are rarely found. Ron Iddles said this is because they have planned their disappearance in a manner to suggest they have mysteriously disappeared rather than ended their lives. “Yes, some might die from an accident, falling off a cliff or drowning, and a very small percentage might have been murdered, but I would think the great majority have planned their own end.”

Ron Iddles had the lugubrious face of a man who’d seen too much. The sad-eyed detective spoke softly, and though what he said was often bluntly factual, it was always heartfelt. “They don’t want the family to feel they have abandoned them, so they think ending their life in a secret place, concealing their body, will make it easier for their families,” he said. “But they are wrong. It makes it so much worse.”

How right Ron was, I would eventually learn.

I was filming a story about Daniel, a 25-year-old Geelong man who one morning in 2011 walked from his parent’s home never to be seen again.

His family was sure he was alive. He was young, athletic, popular and handsome. He had started his own business and had everything to live for.

His sister Lauren organised a global online campaign “Dan Come Home”. The feedback was enormous with reported sightings around the country. Two months after Dan disappeared two women working in a Queensland medical centre reported seeing him. Lauren flew to Brisbane where she viewed CCTV footage of a haggard looking young man whom she identified as her brother. I watched the recording with the family and their conviction it was Dan proved infectious. The picture quality was good, and I felt that surely a sister and parents’ recognition must be irrefutable proof of life. In fact, I was by now well onboard with the all too common “they are still out there somewhere” syndrome.

Ron Iddles had also seen the footage. With the world-weary resignation of an old cop who has seen it all before, he told me, “They want to believe it is Daniel.

“Who would seem to be the best person to identify him? You might think it’s the mother but if it is him, where is he? Why hasn’t he contacted them?”

“But the mother, father and sister who know him so well are convinced that is him and that he is alive,” I said.

Ron was sceptical, “Look, sometimes people see or believe what they want to believe. Our role is to be objective and sometimes that upsets people. So, I have said to his mother, it might be him, but it may not be him.”

Like the family, I thought the police might have done more. I was prepared to overlook Daniel’s medical history of depression, not because it didn’t fit my story, but as I now realise, when journos get too close, they can become hostage to the heartbreak and the desperate hope. It happens all the time. We are only human; believe it or not.

Five years after Daniel’s disappearance his father discovered the body hidden beneath the family home. His son had secreted himself in a tight, dark and almost inaccessible recess between the foundations and the bedrock. There he had ended his life.

It was a tragedy made worse by the total unawareness of the family in the house above, who for years were working tirelessly for the return of their much-loved son and brother.

Even while I interviewed them and listened to their deepest belief that Daniel was still alive, all the time he was there, dead beneath our feet.

Is there anything to learn from this terrible story?

Ron Iddles told me that while the families of the missing often felt the police weren’t doing enough, he felt targeting mental health might be a better use of money and effort.

For me the case of Daniel was a salutary reporting experience. It is too easy to be misled into looking for complexities when the awful truth can be so much less complicated and worse, quite possibly avoided. The 30,000 people reported missing every year is an impossible load for the police. Even the 1500 who never return represents three times the annual homicide numbers. Clearly this problem is beyond policing.

Over decades we haven’t seemed to put a dent in the numbers of the missing. According to Ron Iddles, more coppers on the beat won’t fix the problem. He reckons, “We need to go back to the root cause, that’s mental depression, and that is what we should tackle as a society.”

Since 2016 when Daniel’s body was discovered under his family home, I have agreed with the grim realism of the man they called “Australia’s greatest detective”.

I never covered another missing person story nor until now have I written on this painfully conflicted and heart-rending subject. I share Ron Iddles’s belief: with greater awareness and public recognition of the signs of depression, we might be able to help people find themselves long before they go missing.

If this has raised issues for you call LIFELINE 131 114 or BEYOND BLUE 1300 224 636.

Originally published as Despite rumblings of mutiny Morrison endures rough sea

Read related topics:Scott Morrison