In a lecture about national development and post-war reconstruction, the engineer credited with building the Sydney Harbour Bridge — John Jacob “Job” Crew Bradfield — made his thoughts on massive infrastructure projects abundantly clear.

“We must make no mean plans as mean plans have no magic to stir any man’s blood or awaken enthusiasm in any one,” Bradfield said.

Our Bridge still holds that magic.

Bradfield lived in Gordon on Sydney’s North Shore and commuted into the city each day, catching the train to Milsons Point and then jumping on the ferry to Circular Quay.

Pattering across the Harbour each day to his office, Bradfield, as Robert Freestone, Professor of Planning at the University of NSW, has written, focused his mind on the issue of the growing city’s “north-south connectivity”.

Professor Freestone said that for Bradfield, the Bridge was the “linchpin” of his vision for a city where rapid mass transit could transform people’s lives — taking them by train to the suburbs, away from what Bradfield described as the “general filth and wretchedness” of the inner-city.

“We must make no mean plans as mean plans have no magic to stir any man’s blood or awaken enthusiasm in any one”

Bradfield called the Bridge “the blue arch of heaven”, and “God’s beautiful bow in the clouds”.

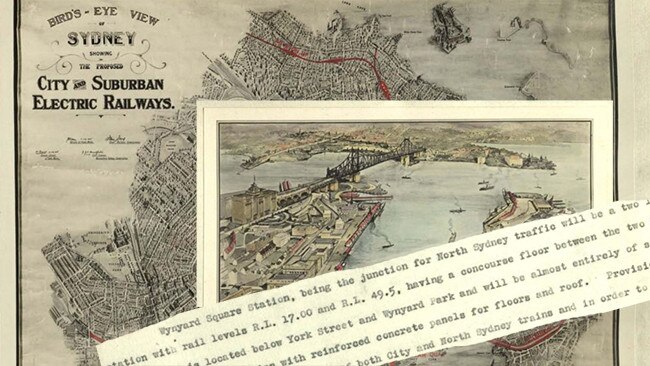

Since the 1800s, city planner had been looking for ways to replace the cross-harbour ferries with a bridge.

In 1911 Bradfield was asked to investigate a crossing, but in1916, a Bill to build a bridge was introduced in NSW Parliament, but defeated due to the priorities of the First World War.

The bridge cost 800 buildings - but changed the city

It was finally enacted in 1922. Tenders were called in 1923 and awarded in 1924 to Dorman, Long & Co. Ltd. a steel manufacturer and bridge-building company in Middlesborough, England.

On 12 January 1932, after seven years of construction, the Bridge, which cost the equivalent of $300 million in today’s money, was handed over to the NSW Public Works Department.

More than 800 buildings in The Rocks, North Sydney and Kirribilli were demolished to make way for the bridge and its approaches, but Bradfield’s “blue arch of heaven” was ready for work.

When asked about the legacy of the Bridge Professor Freestone told The Telegraph that for him, it is “first and foremost a spectacular beacon of the importance of investing in urban infrastructure to create more productive, livable and sustainable cities”.

“John Bradfield was a pioneer in the true sense of the word; Sydney has been built around his grand vision for a connected city.”

“And it further reminds us of the importance of a long term perspective in making such investments; visually and in capacity it is an astonishing forward-looking commitment for the scale of the 1920s Sydney.

It is also not only significant just as a harbour crossing — and a multi-modal one at that — but also as the crucial cog in the even broader vision of an integrated, metropolitan-wide and electrified public transport system; it delivered multiple benefits.

“Finally, it speaks to the power of leadership and vision, evident not only in the extraordinary influence which Bradfield wields but the governments which made the key decisions to make it happen for future generations.”

Today, about 100 people work to maintain the Bridge.

It has been a long-held Sydney belief that painters start at one end of the Harbour Bridge and when they have finished the 52,000 tonne structure, they go back to the beginning and start painting all over again.

Wrong!

The reality is that there are sections of the world’s biggest steel arch bridge that have not felt the tickle of a paint brush since then NSW Premier Jack Lang officially opened the Bridge for business in 1932.

On sections of its massive arch and deep within the steel supports and girders, some of the original lead-based grey paint remains.

Each year the Bridge’s owner — Roads and Maritime Services — spends $20 million to keep her looking her best.

Sydney Harbour Bridge Works Manager Waruna Kaluarachchi has 15 painters, and workers who help prepare the surfaces for painting. They work alongside the riggers who help set up the access platforms for the painters.

He said the exposed surfaces need to be repainted every five years, others last 30 years, but there are sections that have the original paint.

“We can’t start and one end of the Bridge and start painting until we get to the other end. It does not work like that.”

30,000 litres for a single coat

It would take about 30,000 litres of the traditional “Sydney Harbour Bridge Grey” paint to give it just one coat.

The Bridge gets to keep this colour all to herself. Sydney Harbour Bridge grey” is a registered trademark colour and is not for sale on the open market.

Painters like Justin Buhs spray the modern version of the paint, with its protective epoxy material, on with special high pressure nozzles.

But Mr Buhs and his team often resort to old fashioned brushes to reach “the fiddly bits”, especial; y the tops of the six million hand-driven rivets used on the bridge.

His mate Matt Flemming describes himself as an “icon painter”.

‘I used to work at Qantas as an aircraft painter, and I loved doing that, working on the Jumbos.

“Now here I am on the Bridge. I paint Aussie icons. My little girl Lily calls it “daddy’s bridge”.

Mr Kaluarachchi, an engineer who has worked on the Bridge for more than 10 years, said workers come to “love the Bridge”.

“They really take ownership of it,” he said. “It’s more than a job to them.”

The uphill struggle: Climbing the Bridge

by TAYLOR AUERBACH

NOT for the first time in the history of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, bureaucracy stood in the way.

Paul Cave was part of a group from the Young Presidents Organisation that scaled the famous arch in 1989.

Instantly, he knew it was an experience he had to share with the public.

But — like the men and women who built the bridge — he faced an uphill battle to have that dream realised.

“He had quite a few obstacles to say the least,” said Ash Millet of BridgeClimb Sydney.

“Of course the answer was going to be no.”

After Mr Cave approached the government he was sent back a list of more than 70 reasons why BridgeClimb could not go ahead.

“You can imagine safety would have been a big one,” Ms Millet said.

In an example of the nightmare facing Mr Cave, CityRail wanted climbers to wear bright fluoro jumpsuits so they could be easily spotted. The RTA wanted climbers to wear greyish jumpsuits so they would blend into the backdrop of the bridge and not become a distraction.

But, in the spirit of John Bradfield himself, Paul Cave did not relent and managed to pull off a series of complex negotiations with the relevant bodies.

“He addressed every single reason and sent back a letter saying ‘I’ve addressed every single reason.’

“He was incredibly persistent.”

BridgeClimb finally got the go-ahead in 1998 and has been taking Sydneysiders and tourists to the top of Bradfield’s masterpiece ever since.

“In the 20s these guys were writing the laws of engineering,” said Ms Millet.

She has led nearly 1000 climbs to the top of the Harbour Bridge and said the highlight of the journey is always topping the span.

“It still gets that buzz, it’s a massive tick of everyone’s bucket list,” she said.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.