The bomber shuddered. Tortured metal screamed. Failing engines whined. One of Australia’s most famous World War II bomber pilots braced his feet against the console as he heaved back on the control stick, struggling to keep the Lancaster in the air. ‘Bail out, now!’ he bellowed.

PILOT Officer Les Knight, RAAF, was flying a four-engined Lancaster of 617 Squadron. On September 16, 1943, he sacrificed his life to save his seven-man crew — and those in an unsuspecting Dutch village below.

It was not in vain.

The Victorian was able to keep the stricken aircraft high enough and steady enough long enough for all to scramble out the escape hatch.

Knight did not follow them.

He knew that the instant he released his grip on the controls, the bomber would plummet towards the ground.

Knight had seen the village of Den Ham ahead. So he continued to wrestle with his dying aircraft, steering it away from the rural cluster of houses as it continued to lose height.

All of his crew survived.

Their gratitude knew no bounds.

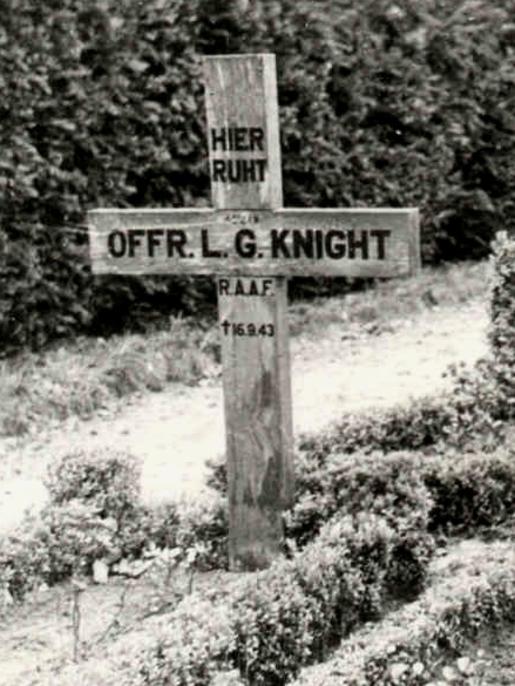

The village of Den Ham also never forgot the courage of Knight’s final act. His grave is well maintained. And a remembrance ceremony is being held on the 75th anniversary of his death.

Australia, however, has forgotten.

RISE TO FAME

Leslie Gordon Knight was born in the Melbourne suburb of Camberwell on March 7, 1921.

After completing school, he took up a clerical accounting job for World War I veteran Len Carter - who soon became a close friend.

Knight couldn’t ride a bike or drive a car. But he applied to join the RAAF in 1941.

His parents were skeptical. His father, Harry, told The Sun in 1943 that he thought his boy, who had stayed home most nights to study, could never make a pilot - stating Les had no aptitude for tools ... no mechanichal skill.

He was soon sent to embattled England.

Posted to 50 Squadron in September 1942, the crew he was assigned there would mostly stay with him until the end.

Knight had survived an extraordinary 26 missions before being offered a secret mission. He was clearly an exceptional pilot. He was well respected by his crew.

Knight conferred with the men under his command: all volunteered to take part, together — even though they had no idea what they were up for.

He was a retiring type. He rarely appeared in photographs and didn’t take part in celebrations when medals were being handed out.

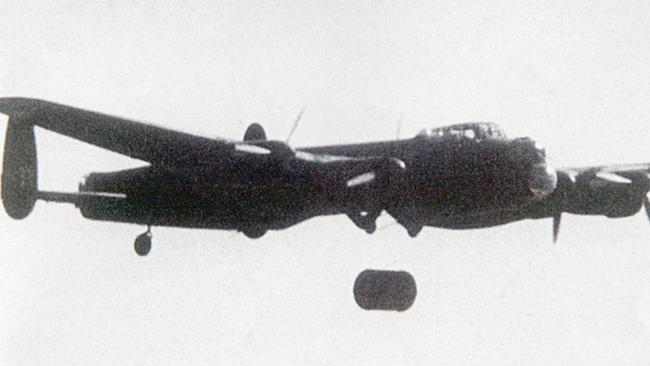

Knight had won international fame for his role in the ‘Dam Busters’ raid — Operation Chastise — against Germany. He was flying the last aircraft in the attack wave, Lancaster AJ-N.

The Mohne Dam had already been breached. But the Eder Dam still stood firm.

Those ahead of him had failed to crack the imposing concrete edifice. Knight himself had been forced to abort his first run. Tail-gunner Harry O’Brien later said ‘he never thought they would get over the mountain’ on the other side of the dam — the Lancaster being so heavily laden by the ungainly bouncing bomb.

But, under full emergency power, Knight did. And he was soon nosing the aircraft back into position for a second, more dangerous, attack run.

He was carrying the last bouncing bomb.

His was the last chance at making the costly mission a success.

But what Knight had learnt from his failed first approach allowed him to place the radical weapon he had carried so far precisely on target.

AJ-N’s Flight Engineer, Sergeant Ray Grayston, reported: “There were only a few seconds involved here before you get level then release — five or seven seconds. As luck would have it, we flattened her out, got the speed right, all the rest doing their job, calling the airspeed, looking at the altimeter lights and calling high or low, and we were spot on, releasing the mine and blew the bottom out of the Eder Dam”.

The raid, however, came at a terrible cost.

In all, 133 aircrew were involved — 53 of them died. On the ground, some 1300 were killed by the bombs and floods.

Knight was awarded a Distinguished Service Order medal for his role that night. His navigator, Harold Hobday, and bomb aimer, Edward Johnson, were given Distinguished Flying Crosses.

Overall, the victory was significant. But there was a lot of war left to fight.

FINAL FLIGHT

Four months after the Dam Busters raid, the elite 617 Squadron was given another difficult task. Code-named ‘Garlic’, their mission was to bomb the Dortmund-Ems canal in Ladbergen, Germany. It was a vital supply route. As such, it was heavily defended.

Just getting there was an almost impossible task.

The big Lancaster bombers had to fly at — and sometimes even below — treetop height, at night, to avoid being spotted by radar and lookouts.

The pilots of 617 Squadron had been trained for just such a job.

But the odds were against them.

And, on September 16, Les Knight’s number came up.

He was flying with the same crew he had carried against Eder Dam, with one extra gunner.

It had been a long, eventful flight over darkened, occupied Europe.

And once 617 Squadron arrived at the canal, it was found to be covered in thick fog.

Knight was lining up for a bombing run at the height of just 30m when, out of the murk, a tall clump of trees appeared. He couldn’t haul the heavy aircraft up fast enough.

It ploughed through the treetops, shredding the branches with the propeller blades of its two port (left) Merlin engines and the leading edges of its wing.

Knight quickly realised he could not complete his attack. He struggled to keep the Lancaster stable and on course. But it was a fight needing all his strength and skill.

According to The 1951 book The Dam Busters by Paul Brickhill, Knight radioed his flight commander: “ ‘Two port engines gone. May I have permission to jettison bomb, sir?’ It was the ‘sir’ that got Martin. Quiet little Knight was following the copybook procedure, asking respectful permission to do the only thing that might get him home. Martin said, ‘For God’s sake, Les, yes,’ and as the bomb was not fused Knight told Johnson to let it go. Relieved of the weight they started to climb very slowly …”

But it wasn’t enough

FIGHT FOR LIFE

Knight’s radio operator, Bob Kellow, would later recall in his book Paths to Freedom the struggle to keep the Lancaster in the air:

“We had crossed the Dutch/German border and were about halfway to the Dutch coast. We all knew that at this height and with only one motor working properly our chances of getting back to England were slim. Les had asked our rear gunner, ‘Obie’ O’Brien, to go to the front gun turret … ‘OK, I’m in the turret, Les. What do you want me to do?’ ‘Good, now reach along below my feet Obie and see if you can find a loose, broken cable,’ said Les. ‘It belongs to the starboard rudder. When you find it, pull on it for all you’re worth.’ In a few minutes, Obie announced that he’d found the cable and was pulling it. The plane began to swing slowly to the right. It was only then that I realised that we’d been steadily swinging to the left for the past few minutes. …”

While the bomber could now be steered, attention focused on keeping the engines running.

Things were not good.

The flight engineer warned the starboard (right) inner engine was overheating and needed to be stopped. It represented half the bomber’s remaining horsepower.

“Try to hold it a bit longer, Ray” Kellow recalled Knight as asking.

The tail-gunner was tiring from having to keep the rudder cable tight continually: “OK Obie, but pull on it again as soon as you can,” Kellow says Knight kindly asked.

Paul Brickhill, in The Dam Busters, added: “The controls were getting worse all the time until, though he had full opposite rudder and aileron on, Knight could not stop her turning to port and it was obvious that he could never fly her home. He ordered his crew to bale out and held the plane steady while they did.”

Kellow described the fateful decision: “It was clear Les was putting on a superhuman effort to keep our crippled plane on some sort of course, but I knew we couldn’t go on much longer. The plane was down to 1000 feet (300m), and the glide angle was steadily increasing … ‘Send out that we’re bailing out, Bob,’ Les said to me. I unhooked my morse key and began tapping out the message.”

This is one of four photo’s taken secretly and at great danger by a local schoolteacher, Meester Snel. In the background a coffin is being put into a horse drawn hearse. Picture: www.rememberingdambusterlesknightdso.org

LAST MOMENTS

Kellow recalled the last he saw of his pilot, Les Knight:

“I stood by him as he firmly held the wheel and tried to keep ‘Nan’ on a steady course, making it easier for each man to jump out. Like a sea captain, he wanted to be sure everyone was safely off before he abandoned ship. His parachute was clipped onto his harness, and he looked searchingly at me, probably wondering why I hadn’t jumped already. Using signs, I asked if he was OK. He nodded his answer, and a wry smile puckered his mouth. With a last smile, I gave him the thumbs-up sign, checked my parachute and took my position at the edge of the escape hatch. Then I bent forward with my head down and tumbled out into the dark Dutch night.”

The crew of Lancaster AJ-N drifted to earth in the darkness around Dam Ham. Two were quickly taken prisoner by German forces.

The remaining five, however, were found by the villagers. At significant risk — they knew that they and their families would be shot if caught — the townspeople hid them.

Resistance forces were contacted. Underground ‘railways’ activated.

All five were soon back safely in England.

Knight guided the bomber towards a field to attempt a crash-landing. But there was a hidden ditch running along a fence line. The Lancaster exploded upon impact.

Those who rushed to the scene found an almost unrecognisable tangled mass of struts, panels and engine parts. Les Knight’s body was retrieved the next morning and carried away by cart.

He was buried in the village’s old graveyard.

The funeral procession conducted by the townsfolk of Den Ham after Les Knight flew his striken bomber into a nearby field to avoid casualties. Picture courtesy Mrs Fay Gerber

LEST WE FORGET

A Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone now stands in place of the simple timber cross which initially marked his plot. A memorial stone stands where his bomber went down.

Word quickly spread among Dam Ham’s residents about Knights decision to stay with the plane and keep it from crashing among them.

They’ve never forgotten.

Now, the village has organised a special event for the 75th anniversary. The families of the crew have been invited, as have those of the underground resistance members who helped the five evade capture.

A memorial plaque was also placed in the parish church of Knight’s Victorian home. No commemorative event is understood to be planned.

President of the Toorak RSL Michael Fogarty says Les Knight’s courage and critical role is still remembered by the branch’s Bomber Command Commemorative Association.

He’s worried others are beginning to forget.

“Being a baby boomer the story of the Dam Busters seemed quite futuristic, but nowadays ...”, he said. “Even so, I had no idea that one of the Dam Buster pilots was Camberwell’s own hero. Sadly very few aware of Les Knights courage and the critical roll he played.”

Mr Fogarty says one possible reason for the story being forgotten was Bomber Command had received a lot of bad publicity due to the devastating firestorms inflicted upon German cities. But its pilots had suffered one of the worst casualty rates of the entire war.

“In a way, they’re all heroes,” he said. “My main aim is to give them some recognition, and by recognising Knight we’re acknowling the effort of all of them.”

Les Knight, pictured at his Bowen St, Camberwell, home before shipping out to Britain. Picture courtesy Mrs Fay Gerber

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Who Owns Tassie’s farms: Biggest investors, landholders named

An annual investigation can reveal Tasmania has been a key destination for capital in the race to invest in Aussie agriculture. See the full list.

Families, billionaires and foreign owners of SA’s largest farms revealed

From sprawling stations in the north to prime cropping in the south – meet those who own South Australia’s largest farming properties. See the full list.