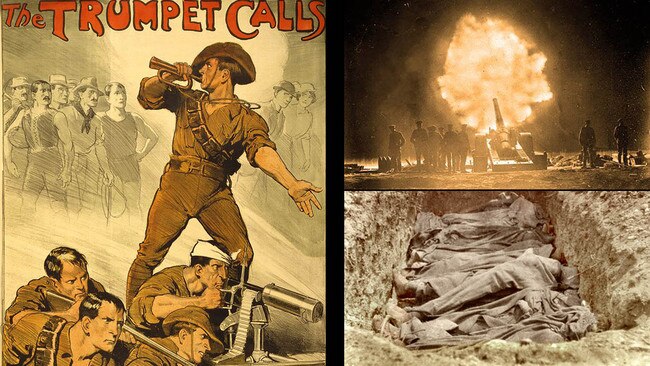

FOUR months after the Anzacs hit the beach at Gallipoli in April 1915, a young Australian journalist visited the battlefront. What he saw first-hand and learned from soldiers and other correspondents, bound by strict censorship from reporting the truth, horrified and angered him.

The campaign, so glowingly spoken of at home, was a shambles, wasting lives and resources, with no end in sight. The journalist, Keith Murdoch, knew the reality must be exposed.

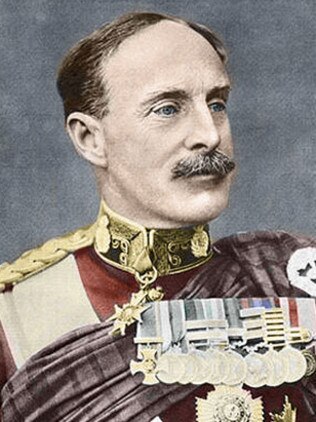

Despite being arrested, he defied the military censors and went straight to the top — detailing the horrors and bungling in a now-legendary letter to Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, a family friend. With the secrecy blown away, key opinion finally turned against the campaign — and 12 weeks later the troops were evacuated.

This is the letter that changed the war:

High Commissioner’s Office, London.

September 23, 1915

Personal

Dear Mr. Fisher.

The Cabinet will, ere this reaches you, have dealt with my report on A.I.F. (Australian Infantry Force) mails and wounded, so it is no good my saying more in these subjects, other than this, that if you allow the inert mass of congealed incompetency in the Postal Department to keep you from instituting alphabetical sorting by units, 75 per cent. of our unfortunate homesick men in hospitals and at base depots will continue to receive no home letters.

It is of bigger things I write you now. I shall talk as if you were by my side, as in the good days. In my last hurried note I could deal only with a few urgent matters affecting Australian administration, especially those concerning appointments of senior officers and treatment of wounded.

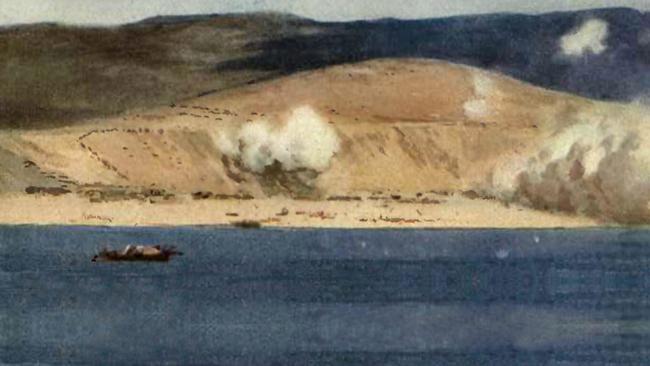

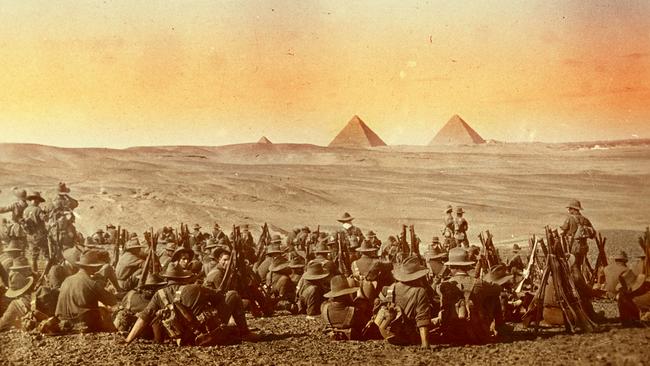

I now write of the unfortunate Dardanelles expedition, in the light of what knowledge I could gain on the spot, on the lines of communication, and in Egypt. It is undoubtedly one of the most terrible chapters in our history. Your fears have been justified.

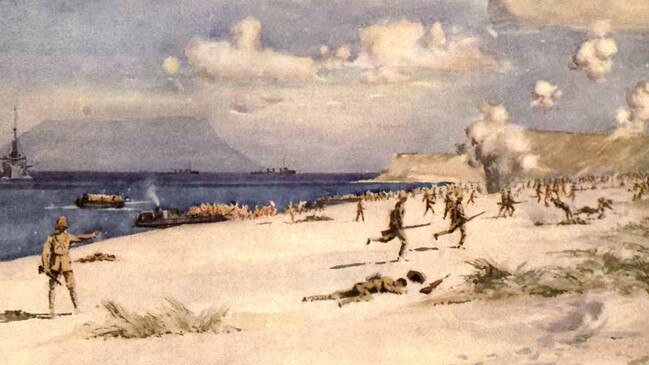

I have not military knowledge to be able to say whether the enterprise ever had a chance of succeeding. Certainly there has been a series of disastrous underestimations, and I think our Australian generals are right when they say, that had any one of these been luckily so unEnglish a thing as an overestimation, we should have been through to Constantinople at much less cost than we have paid for our slender perch on the cliffs of the Peninsula.

To fling them, without even the element of surprise, against such trenches as the Turks make, was murder

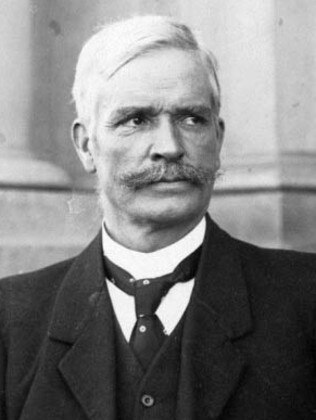

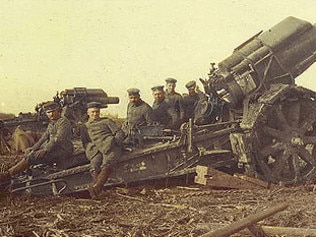

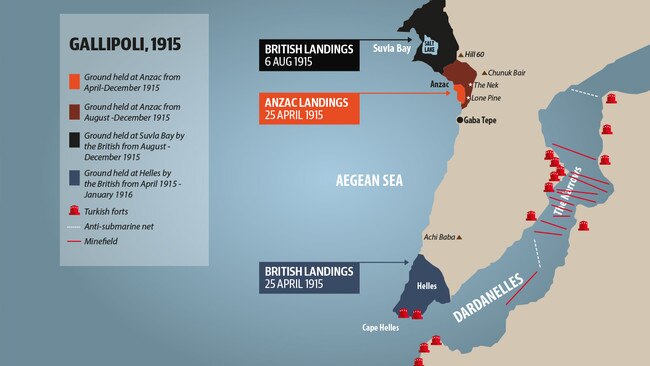

The first two efforts, those of the fleet alone and of the combined forces in April-May, failed miserably mainly because London expected far too much from floating artillery.

It is only now being recognised that the naval guns, with their flat trajectory, are of little avail against the narrow Turkish trenches.

The last great effort, that of August 6-21, was a costly and bloody fiasco because, in addition to wretched staff work, the troops sent were inadequate and of most uneven quality.

That failure has created a situation which even yet has not been seriously faced — ie, a choice between withdrawal of our armies and hanging on for a fresh offensive after winter.

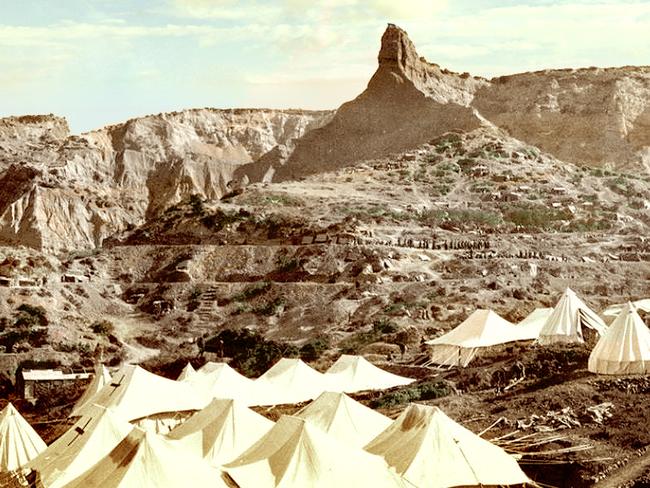

Unfortunately I was not in time for any of these big operations, but I visited most parts of Anzac and Suvla Bay positions, walked many miles through the trenches, conversed with the leaders and what senior and junior officers I could reach, and was favoured in all parts with full and frank confidence.

I could not visit Helles, where we have about 25,000 men and many animals and cars (armoured cars hidden helpless in trenches).

We have abandoned our intentions of taking Achi Baba by frontal assault.

This was always a hopeless scheme, after early May, and no one can understand why Hamilton persisted with it.

Achi Baba is a gradual, bare slope, a mass of trenches and gun emplacements, but so little did the General staff know of its task that it expected to storm it with ease.

Indeed, the General staff sent our artillery horses and ambulance transport with our landing parties in April, as if the Australasian Army Corps could get astride the peninsula in a few days, I assure you that if our landing had been at Gaba Tepe as proposed, only a few broken remnants of our magnificent force would have reached the first defensive line.

Having at last abandoned his expensive design to storm Achi Baba, Hamilton is keeping his divisions at Helles merely to hold a corresponding body of Turks.

Helles is therefore the most quiet of the three zones, though even there, every yard of ground is commanded by the enemy’s guns, and even the beaches are frequently shelled.

That is the only sort of advance we can make from Anzac proper.

The Lone Pine affair was partly in the nature of a holding movement, and it certainly succeeded in holding a large body of Turks, who maintained a series of fierce counter-attacks for 82 hours, during which the Suvla Bay operations were in progress.

Suvla Bay is a shallow, open indentation in the thickest part of the peninsula, about two miles and a half to the left of Anzac. The flat country leading from the beach consists mostly of a marsh called Bitter Lake, which in winter becomes a great morass.

After heavy rains the flat is inundated.

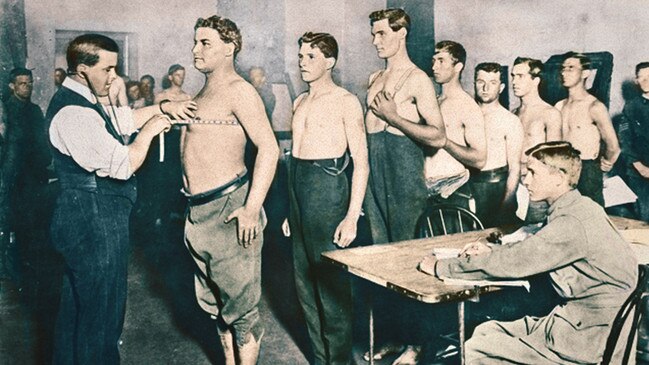

On this flat in August nearly 90,000 men were landed.

They were New Army and Territorial divisions. They had spent a fortnight on the water, in transport which even the most careful arrangements could not make wholesome.

I was on the lower deck on one of these, and the place was putrid.

The place was putrid ... packed like sardines

The men could not be allowed on shore at ports of call. One or two regiments were given route marches, but the long spell of ship life was surely in every case weakening.

Those which were to land first were given landing practice at Mudros (advanced base) and Imbros (headquarters base), but many were set ashore direct from their ships at Suvla.

In addition to the ordinary weakening effects of troopships was the nervous strain of expectations of submarines. Most of the men ignored this but I was on the Beltana when a submarine was sighted and fired at, and I know that this strain did exist.

You can imagine, then, that these fresh, raw, untried troops, under amateur officers, homesick and apprehensive, were under normal in morale when the day of landing approached.

They had to be packed like sardines on the trawlers and small destroyers and vessels for the actual landing, and were kept like this for most of the afternoon and the whole of a night.

Before this embarkation, they had each received three days’ supply of iron rations — biscuits and bully beef — and had filled their water bottles — one bottle to each man.

Then in the early hours came the landing, when the life of men is at its lowest.

Before the new troops had advanced any distance they were being racked with shell fire

I do not say that better arrangements could have been made. But I do say that in the first place to send raw, young recruits on this perilous enterprise was to court disaster; and Hamilton would have some reasonableness behind his complaints that his men let him down, if he and his staff had not at the same time let the men down with grosser wrong-doings.

The landing was unopposed; the Turks were taken completely by surprise. But with great celerity they galloped their artillery round, and opened fire also from their forts. Before the new troops had advanced any distance they were being racked with shell fire.

I am informed by many officers that one division went ashore without any orders whatsoever. Another division, to which had been allotted the essential work of occupying the Anafarta Hills, was marched far to the left before the mistake in direction was noticed. It was then recalled, and reformed, and sent off towards the ridge.

As a practical man, how much water do you think would be left in those thirsty English boys’ bottles by this time — after the night on the seas, and the hot march out, march back, and advance? Of course, not a drop. And yet the staff professes surprise that before noon the men were weak for want of water.

The whole army suffered intensely from thirst during the next three days. There were many deaths from thirst. One general even assured me that the collapse on Anafarta Hills was due to thirst. Certainly these hot-blooded young men, scions of the thirstiest race in the world, were sent out into tropical heat with food calculated to engender fierce thirst, and without water.

The divisional commanders have a just grievance against the general staff when they say that they were sent out not only with indefinite orders and without a good knowledge of the country over which they were to advance, but without water and with little or no knowledge of the few muddy wells existing in these parts.

I am of course only repeating what I have been told on all hands. But you will trust me when I say that the work of the general staff in Gallipoli has been deplorable. The general idea, that of getting astride the peninsula and cutting the line of communications connecting the southern Turkish army with its bases, was good. I understand it was Birdwood’s scheme.

The only criticism I have heard against it is that the great left flank movement from Anzac, which was directed against Hill 971 and Chunuk Bair while the Suvla Bay operations were in progress, was wasteful, inasmuch as the splendid Australasian troops, Gurkhas and Connaught Rangers broken to pieces in this advance could have been shipped to Suvla, and there need as the main wedge in the great effort to cross to Maidos.

Splendid Australasian troops broken to pieces in this advance

I discussed this criticism with our Australian staff, and found a decided opinion that the occupation of the heights assailed was essential to the success of the Suvla advance, owing to the dominating influence of Hill 971 and Chunuk Bair.

The 9th Army Corps reached Anafarta Hills, but could not maintain their position. Of the terrible manner of their retreat I need not tell you in this letter.

One of our generals, who had his men trying desperately to hold on to the shoulders of 971 and Chunuk Bair (only a few Gurkhas really reached 971 and a few Australasians Chunuk Bair), was staggered to see the 9th and 10th Corps retreat, at the very time when their firm holding was essential.

He was staggered by its manner, and principally by the obvious conflicts and confusions between British Generals, due I am told to the disinclination of two of them to accept orders from De Lisle, who though junior had been placed in command after the recall of General Stopford.

At least two generals 120 were recalled at once — Stopford, who has an army corps, and Hamersley who suffered once from lapse of memory, but who was thought good enough by London for this work of supreme importance to the Empire. I am told that a second division commander was recalled. Diverse fates were in store for Brigade commanders — at least one, Kenna, V.C., was killed in action.

The August 6-10 operations at Suvla left us holding a position which is nothing more than an embarrassment. We are about one mile and a half inland; but we do not hold a single commanding point nor one of real strategic value, and our one little eminence, Chocolate Hill, is I am assured by artillery officers, perilously unsafe. It is commanded by those crests on which masses of Turks are perched; and by screened artillery at which we cannot possibly get.

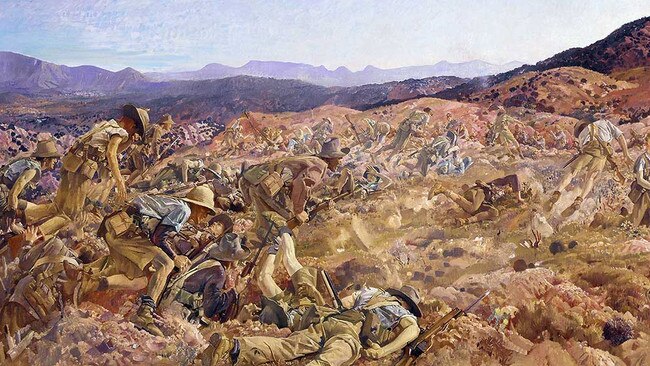

Perhaps this awful defeat of August 6-10, in which our Imperial armies lost 35 per cent of their strength — fully 33,000 men — was due as much to inferior troops as to any other cause. But that cannot be said of the desperate effort made on August 21, after the Turks had had plenty of time in which to bring up strong reinforcements and to increase the natural strength of their position, to take their positions by frontal assault. Some of the finest forces on the peninsula were used in this bloody battle. The glorious 29th Division, through which 40,000 men have passed, and which is now reduced to less than 5,000 men, were specially brought up from Helles, and the Mounted Division of Territorial Yeomanry were brought over from Egypt.

They and other troops were dashed against the Turkish lines, and broken.

They never had a chance of holding their positions; and the slaughter of fine youths was appalling

They never had a chance of holding their positions when for one brief hour they pierced the Turks’ first line; and the slaughter of fine youths was appalling. My criticism of that, as these troops were available, they should undoubtedly have been used in early August; and to fling them, without even the element of surprise, against such trenches as the Turks make, was murder.

One word more in this very sketchy and incomplete story of the August operations. It concerns the heroic advance of Australasian, Gurkha and Connaught Rangers troops from our left flank at Anzac. It was made from a New Zealand outpost, heroically held during the long summer months away to our left, and connected with our main position by a long sap. The NZ Rifles swept the hills of snipers, and were practically wiped out in doing so.

Through them advanced the Wellington Brigade, other New Zealand forces, The Gurkhas and Irishmen, and our magnificent Fourth Brigade, brought up to a strength of far over 4000 for the event.

The advance through broken, scrubby, impossible country in the night, despite mistakes by guides and constant bayonet fighting, was one of the most glorious efforts of the Dardanelles.

There is a disposition to blame Monash for not pushing further in, but I have been over the country, through the gullies and over the hills, and I cannot see how even as much as he did could have been expected. Of course, our men did not hold even the shoulder of Chunuk Bair; but only a few hundred reached it, after most desperate hand to hand fighting, and they were swept off by an advance of more than 5000 Turks. We did not have enough men for the operation, It was a question of depth and weight; and it is sad to think that we gained our objective, all but the highest slopes, and that we had not sufficient reserves to stay there. Even if Anafarta Hills had been held in support of us, we could not have stayed on this vital Chunuk Bair with the forces at our disposal.

The heroic Fourth Brigade was reduced in three days’ fighting to little more than 1000 strong. You will be glad to know that the men died well.

I must leave this story, scrappy as it is, of the operation, to tell you of the situation and the problems that face us.

I will do so with the frankness you have always encouraged.

Winter is on us, and it brings great dangers. We have about 105,000 men and some 25,000 animals — 90 per cent mules — on the Peninsula. About 25,000 of these are at Helles, 35,000 at Anzac, and the rest at Suvla. Suvla and Anzac are now joined, thanks to the brilliant Australasian work on the left flank; and it is important to remember that there are two retreats from Suvla, one to Anzac, the other by sea. These are all that remain of fully 260,000 men. Nowhere are we protected from Turkish shell.

Our holdings are so small and narrow that we cannot hide from the Turks the position of our guns, and repeatedly damage is done to them.

On the other hand, the Turks have a vast country in which to select gun positions, they can change them with ease, and we cannot place them.

You would marvel at the impossibility even of getting at the guns enfilading Anzac from the right. These are hidden in an olive grove under Killid Bair plateau, and continuous efforts on the part of warships and our own finely operated artillery have been resultless.

These guns have direct fire on our beaches, and frequently cause serious damage. All three positions are so exposed that one wonders why the Turks do not drive us out with artillery fire.

Helles is the most secure of all; but Anzac and especially Suvla are very much exposed. Had the Turks sufficient modern artillery and shells they could make Suvla unbearable and Anzac an even worse hell than it is. Our staff has various opinions about the Turkish supply of shells. But it seems certain that there is an even greater shortage amongst us. Otherwise, the Turks are saving their shell for serious winter offensives. I must say that the theory that the Turks are really short of shells did not impress me. I frequently watched them waste three shrapnel shells on the mere sport of making a trawler up-anchor and move out to sea.

Of course, trawlers are occasionally hit; but the Turks cannot take such shell-fire seriously. I have seen as many as eight shells fired at two trawlers. One day recently 60 shells were placed by the right flank enfilading guns on the New Zealand beach. They caused damage and cost us 65 men; but they showed also that the Turks are not very short.

At the same time, one wonders whether the Turks are not merely playing with us, holding us there until they are helped by nature to drive us out. But that idea is discounted by the fact that the Turks have made many serious and costly efforts to get rid of us.

At Helles, the narrow cape gives some sort of protection from the waves, but it would be absurd to think that even this will permit of the landing of supplies in rough weather. Two steamships have been sunk to provide a breakwater, with the careless disregard of expense which has marked the whole of this unfortunate enterprise. These ships are even now, in the early days of autumn, rolling from side to side with the slight sea swell.

At Anzac, there is only open anchorage. We have made three small wooden piers, each of them banked on one side with sand-bags as a protection for the men against shells. But against these the water barges are beginning to sway dangerously. At Suvla more ships are to be sunk. There can be no sort of safe landing place there either.

Can we keep the armies supplied with food, munitions and drafts? Many mariners and some naval men say no.

I discussed this question with naval transport officers on the staff ship in Mudros, including a high and responsible official, and I am assured that the work can be done. It will mean great costs.

The Navy says, in effect, that great reserves must be stored up in spells of calm weather, and that at times it may be necessary to get stuff ashore by running a supply ship on to the beach, from which the goods will have to be taken by the beach parties under the concentrated and accurate fire of the enemy’s artillery.

The trenches are summer trenches, and the dug-outs mere protection against shrapnel, not against weather

I do not think, therefore, that the question of rough seas is vital.

But certainly, should as I hope the Cabinet decide to hang on through the winter for another offensive, or for peace, we are faced with serious dangers from cold rain and snow on land. All our engineering work has been done with the idea that our positions would be evacuated by winter; and the roads are made in winter water-courses, the trenches are summer trenches, and the dug-outs mere protection against shrapnel, not against weather.

All this means tremendous structural changes, and the immediate construction of good roads. And I fear that the decision has been left too late for such work to be thoroughly undertaken before the winter is upon us. No structural material had reached Anzac when I left. Nor had the food reserves amounted to more than 14 days’ supplies.

Perhaps the most vital danger from weather is that, before the rains come to end all our water troubles, there will be a spell of bad weather at sea that will prevent us from getting water ashore, and our troops will have a grave water shortage added to their other trials. No water supply for a month would raise questions of the utmost gravity.

But we can overcome weather troubles at Helles and Anzac, and even at Suvla also, though General Byng asserts that he cannot keep his forces there when the Lake cuts his positions in twain, unless he can bridge the immense width of this strange seasonal stretch of water. What is more serious is the question of Turkish attacks during the cold, wet winter months.

There is a grave possibility of a German army appearing on the scene

They cannot drive us from Anzac. Of that I am sure. Australasian ingenuity and endurance have made the place a fortress, and it is inhabited and guarded by determined and dauntless men.

But Suvla is more precarious. I am not prepared to say that Suvla can be held during winter.

There is a grave possibility of a German army appearing on the scene. In any case, the arrival of a number of heavy German guns might be quite sufficient to finish our expedition off. Big German howitzers could batter our trenches to pieces, and we would have no reply. And remember that several of our vital positions, such as Quinn’s Post, are only a few small yards of land on the top of a cliff — mere footholds on the cliffs.

Whether the Germans get their guns through or not, we must make up our minds that the Turkish activity will be much greater in winter than ever before. The enemy will be able to concentrate his artillery, when he knows that we are no longer threatening any of his positions. He will be able to drag across great guns from his forts, and give any position of ours a terrible mauling. We will have great reinforcements within reach, unless the published stories, and the tales of travellers, of his large new levies are quite untrue.

We have to face not only this menace, but the frightful weakening effect of sickness. Already the flies are spreading dysentery to an alarming extent, and the sick rate would astonish you. It cannot be less than 600 a day. We must be evacuating fully 1000 sick and wounded men every day. When the autumn rains come and unbury our dead, now lying under a light soil in our trenches, sickness must increase. Even now the stench in many of our trenches is sickening. Alas, the good human stuff that there lies buried, the brave hearts still, the sorrow in our hard-hit Australian households.

Supposing we lose only 30,000 during winter from sickness. That means that when spring comes we shall have about 60,000 men left. But they will not be an army. They will be a broken force, spent. A winter in Gallipoli will be a winter under severe strain, under shell-fire, under the expectation of attack, and in the anguish which is inescapable on this shell-torn spot. The troops will in reality be on guard throughout the winter. They will stand to arms throughout long and bitter nights. Nothing can be expected from them when at last the normal fighting days come again. The new offensive must then be made with a huge army of new troops. Can we get them? Already the complaint in France is that we cannot fill the gaps, that after an advance our thinned ranks cannot be replenished.

But I am not a pessimist, and if there is really military necessity for this awful ordeal, then I am sure the Australian troops will face it. Indeed, anxious though they are to leave the dreary and sombre scene of their wreckage, the Australian division would strongly resent the confession of failure that a withdrawal would entail.

They are dispirited, they have been through such warfare as no army has seen in any part of the world, but they are game to the end.

On the high political question of whether good is to be served by keeping the armies in Gallipoli, I can say little, for I am uninformed. Cabinet Ministers here impress me with the fact that a failure in the Dardanelles would have most serious results in India, Persia is giving endless trouble, and there seems to be little doubt that India is ripe for trouble. Nor do I know whether the appalling outlay in money on the Dardanelles expedition, with its huge and costly line of communications can be allowed to continue without endangering those financial reserves on which we rely to so great an extent in the wearing down of Germany’s strength. Nor do I know whether any offensive next year against Constantinople can succeed.

On that point I can only say that the best military advice is that we can get through, that we would be through now if we had thrown in sufficient forces. Whyte, whom we both admire as an able soldier and an inspiring Australian leader, assures me that another 150,000 men would do the job. I presume that would mean a landing on a large scale somewhere in Thrace, or north of Bulair.

We lost five hundred men, squatters’ sons and farmers’ sons, on that terrible spot

Certainly, any advance against the extraordinary strong trenches — narrow and deep, like all the Turks’ wonderful trench work, and covered with heavy timber overhead protection against shell fire and bombs, from our present positions seems impracticable. You would have wept with Hughes and myself if you had gone with us over the ground where two of our finest Light Horse regiments were wiped out in ten minutes in a brave effort to advance a few yards to Dead Men’s Ridge.

We lost five hundred men, squatters’ sons and farmers’ sons, on that terrible spot. Such is the cost of so much as looking out over the top of our trenches.

And now one word about the troops. No one who sees them at work in trenches and on beaches and in saps can doubt that their morale is very severely shaken indeed. It is far worse at Suvla, although the men there are only two months from home, than anywhere. The spirit at Suvla is simply deplorable.

The men have no confidence in the staff, and to tell the truth they have little confidence in London.

I shall always remember the stricken face of a young English lieutenant when I told him he must make up his mind for a winter campaign. He had had a month of physical and mental torture, and the prospect of a winter seemed more than he could bear. But his great dread was that the London authorities would not begin until too late to send winter provisions. All the New army is still clothed in tropical uniforms, and when I left, London was still sending out drafts in this “shorts”. Everywhere one encountered the same fear that the armies would be left to their fate, and that the many shipments of materials, food and clothing required for winter would not be despatched until the weather made their landing impossible.

You would refuse to believe that these men were really British soldiers

This lack of confidence in the authorities arises principally from the fact that every man knows that the last operations were grossly bungled by the general staff, and that Hamilton has led a series of armies into a series of cul-de-sacs.

You would hardly believe the evidence of your own eyes at Suvla. You would refuse to believe that these men were really British soldiers.

So badly shaken are they by their miserable defeats and by their surroundings, so physically affected are they by the lack of water and the monotony of a salt beef and rice diet, that they show an atrophy of mind and body that is appalling.

I must confess that in our own trenches, where our men have been kept on guard for abnormally long periods, I saw the same terrible atrophy.

You can understand how it arises.

It is like the look of a tortured dumb animal.

Men living in trenches with no movement except when they are digging, and with nothing to look at except a narrow strip of sky and the blank walls of their prisons, cannot remain cheerful or even thoughtful.

Perhaps some efforts could have been made by the War Office to provide them with cinemas, or entertainments, but of course Gallipoli is at the end of a long and costly, not to say dangerous, line of communications. This fact is the only excuse for the excess of bully-beef feeding.

The physique of those at Suvla is not to be compared with that of the Australians. Nor is their intelligence. I fear also that the British physique is very much below that of the Turks. Indeed, it is quite obviously so. Our men have found it impossible to form a high opinion of the British K. men and territorials. They are merely a lot of childlike youths without strength to endure or brains to improve their conditions.

I do not like to dictate this sentence, even for your eyes, but the fact is that after the first day at Suvla an order had to be issued to officers to shoot without mercy any soldiers who lagged behind or loitered in an advance.

The Kitchener army showed perfection in manoeuvre training — they kept a good line on the Suvla plain — but that is not the kind of training required at the Dardanelles, and it is a question really whether the training has been of the right kind. All this is very dismal, and they are of course only impressions. But every Australian officer and man agrees with what I say.

At Anzac the morale is good. The men are thoroughly dispirited, except the new arrivals. They are weakened sadly by dysentery and illness. They have been overworked, through lack of reinforcements. And as an army of offence they are done.

Not one step can be made with the first Australian division until it has been completely rested and refitted. But it is having only one month’s rest at Mudros. The New Zealand and Australian Division (Godley’s) also is reduced to only a few thousand men and has shot its bolt. But the men of Anzac would never retreat. And the one way to cheer them up is to pass the world that the Turks are going to attack, or that an assault by our forces is being planned.

I could pour into your ears so much truth about the grandeur of our Australian army, and the wonderful affection of these fine young soldiers for each other and their homeland

The great fighting spirit of the race is still burning in these men; but it does not burn amongst the toy soldiers of Suvla. You could imagine nothing finer than the spirit of some Australian boys — all of good parentage — who were stowed away on a troopship I was on in the Aegean, having deserved their posts in Alexandria out of mere shame of the thought of returning to Australia without having taken part in the fighting on Anzac’s sacred soil.These fine country lads, magnificent men, knew that the desertion would cost them their stripes, but that and the loss of pay did not worry them.

How wonderfully generous is the Australian soldier’s view of life! These lads discussed quite fearlessly the prospects of their deaths, and their view was, “It is no disgrace for an Australian to die beside good pals in Anzac, where his best pals are under the dust.”

But I could pour into your ears so much truth about the grandeur of our Australian army, and the wonderful affection of these fine young soldiers for each other and their homeland, that your Australianism would become a more powerful sentiment than before. It is stirring to see them, magnificent manhood, swinging their fine limbs as they walk about Anzac.They have the noble faces of men who have endured.

Oh, if you could picture Anzac as I have seen it, you would find that to be an Australian is the greatest privilege the world has to offer.

It is only these fighting qualities, and the special capacity of the Australian physique to endure hardship, that keep the morale at Anzac good.

The men have great faith in Birdwood, Walker and Legge — not much in Godley. Birdwood struck me as a good army corps commander, but nothing more. He has not the fighting quality, nor the big brain, of a great general. Walker is a plain hard-hitting soldier. We are lucky in these men.

But for the general staff, and I fear for Hamilton, officers and men have nothing but contempt. They express it fearlessly. That however is not peculiar to Anzac. Sedition is talked round every tin of bully beef on the peninsula, and it is only loyalty that holds the forces together. Every returning troopship, every section of the line of communications, is full of the same talk.

I like General Hamilton, and found him exceedingly kindly. I admire him as a journalist. But as a strategist he has completely failed.

Undoubtedly, the essential and first step to restore the morale of the shaken forces is to recall him and his Chief of Staff, a man more cordially detested in our forces than Enver Pasha.

What the army there wants is a young leader, a man who has had no past, and around whom the officers can rally. I am hoping strongly that Smith Dorrien will not be sent out, because whether he failed or not in France, he will be said to have failed; and the troops on the peninsula must not be allowed to harbour the suspicion that second rate goods are any longer considered good enough for them.

The French call him the General who lives on an Island

I cannot see any solution which does not begin with the recall of Hamilton. Perhaps before this reaches you this recall will have occurred. Do not believe anything you may see about a large reinforcement and a new offensive before the winter. That I fear is impossible. If after the Suvla Bay disaster we had had another hundred thousand men to pour into the peninsula, we might well have got through. But as it is, we hold positions that are nothing more than costly embarrassments. It is not for me to judge Hamilton, but it is plain that when an army has completely lost faith in its general, and he has on numerous occasions proved his weaknesses, only one thing can be done. He has very seldom been at Anzac. He lives at Imbros. The French call him the General who lives on an Island.

The story may not be true, but the army believes that Hamilton left Suvla on August 21 remarking “Everything hangs in the balance, the Yeomanry are about to charge.” Of course the army laughs at a general who leaves the battlefield when everything hands in the balance.

I could make this letter interminable, and I fear that I have only touched very incompletely on a few phases. What I want to say to you now very seriously is that the continuous and ghastly bungling over the Dardanelles enterprise was to b e expected from such a General Staff as the British Army possesses, so far as I have seen it.

The conceit and self-complacency of the red feather men are equalled only by their incapacity. Along the line of communications, and especially at Mudros, are countless high officers and conceited young cubs who are plainly only playing at war. What can you expect of men who have never worked seriously, who have lived for their appearance and for social distinction and self satisfaction, and who are not called on to conduct a gigantic war?

Kitchener has a terrible task in getting pure work out of these men, whose motives can never be pure, for they are unchangeably selfish. I want to say frankly that it is my opinion, and that without exception of Australian officers, that appointments to the General Staff are made from motives of friendship and social influence.

Australians now loathe any Englishmen wearing red ... I could tell you of many scandals

Australians now loathe and detest any Englishmen wearing red. Without such a purification of motive as will bring youth and ability to the top, we cannot win.

I could tell you of many scandals, but the instance that will best appeal to you is that of the staff ship Aragon. She is a magnificent and luxurious South American liner, anchored in Mudros harbour as a base for the Staff of the Inspector-General of Communications. I can give you no idea of how the Australians — and the new British Officers too — loathe the Aragon. Heaven knows what she is costing, but certainly the staff lives in luxury. And nothing can exceed the rudeness of these chocolate general staff soldiers to those returning from the front. The Ship’s adjutant is the worst instance of rude and disgusting snobbishness and incapacity I have come across.

With others, plain downright incapacity is the main characteristic. I must say this of them also, that whereas at our 3rd Australian General Hospital on shore we had 134 fever cases, including typhus, with only a few mosquito nets, and no ice, and few medical comforts, the Aragon staff was wallowing in ice. Colonel Stawell — you know him as Melbourne’s leading consultant — and Sir Alex M’Cormick are not sentimentalists.

But they really wept over the terrible hardships of the wounded, due to the incapacity of the Aragon. One concrete case is that of 150 wounded men landed in dead of night, with no provision and no instructions, at the hospital beach, to make their way as best they would to the hospital, which had no notice of their arrival.

Fiaschi, de Crespigny, Stawell and Kent Hughes will be able to tell you of the absolutely shocking difficulties of this hospital in the face of perpetual snubbing and bungling of the Aragon staff.

While I was at the hospital a beautiful general and his staff rode in to make an inspection. Despite their appearance as perfect specimens of the general staff, I thought, we shall now get the ice from the Aragon on to the brows of our unfortunate men.

But no ice appeared next day.

The navy is very good, and sent some comforts and ice across, but for the three days before my visit this ice had gone astray before it reached the hospital.

I told you in my last letter of the necessity for canteen ships, and need not go into that now, but on the point of the general staff I must say that the work at the bases in Egypt struck me as on a par with that of the Aragon.

Some day you will have to take up the case of Sir John Maxwell. He has a poor brain for his big position, and I assure you that our officers at Anzac have a poor opinion of the work of his lieutenant, General Spens — a man broken on the continent, and therefore thought good enough to supervise the training of Australians — who is controlling our bases.

The question you will have to fight out about Maxwell is this.

After the last disturbance in the Whasa, when a very few of our men burnt some houses in which they had been drugged and diseased, he issued one of his famous lecturing orders, in which he referred to his regret that “even wilful murder” had been mentioned as one of the Australian crimes in Cairo.

In this casual way did he blast the good name of our clean and vigorous army. I inquired as far as was possible, and could hear nothing of even a charge of wilful murder mentioned against any Australian.

This order rouses intense anger amongst our men.

Perhaps we are too sensitive.

Our men were certainly too sensitive in their anger in the trenches when a notice was posted, I think in orders, describing how an unfortunate British Tommy had been shot at Helles at dawn for cowardice.

It was almost amusing to hear our men resent this even remote connection with the Australian forces and a veiled threat of such shooting. “Such things have nothing to do with us,” they said.

Our men feel that their reputation is too sacred to leave in the hands of Maxwell, and they much resent the sudden change in the attitude of the general staff, which regarded them as criminals in Cairo, and now lavishly calls them heroes in Gallipoli.

You will think that all this is a sorry picture, but do not forget that the enemy has his troubles

You will think that all this is a sorry picture, but do not forget that the enemy has his troubles, and that we have certain signs that his morale is deteriorating.

From what I saw of the Turk I am convinced that he is a brave and generous foe, and he is fighting now for dear home, with a feeling that he is winning, and that he is a better man than those opposed to him.

The Turks by the way are as generous in their praise of our men as the British and French are.

Certainly the Turks are positively afraid of our men, and one of their trenches — that opposite Quinn’s Post — is such a place of fear, owing to the indomitable way in which our snipers and bomb-throwers have got their men down, that Turks will not go into it unless they are made corporals. So say our Intelligence Officers.

I saw many strange and remarkable instances of the humanity and courage of the Turks. Certainly his trenches are better than anything we can do, and he makes them remarkably quickly.

One word more to-day. Do for Heaven’s sake make every effort to secure the recall of Sir James Porter, the Englishman in charge of the medical services. Our doctors are without exception furious with him. He made a shocking muddle of the first arrangements for transport of wounded, as I wrote you. The case against him there was unanswerable.

But he has been left in charge, and his muddling continues.

He lives on a luxurious yacht in Mudros. Oh, no Australian has the heart to tell of the fearful wreckage of life due to this man’s incompetency. That is not a wild statement. It is truth. Even now, the great bulk of the wounded are sent to Imbros before being passed on to hospitals elsewhere.

This handling aggravates sickness and wounds, yet the Generals wonder why men sent away from the peninsula with slight sickness become worse and do not (always?) expected, return in a few weeks — do not return at all.

Our Australian doctors have bearded Porter in his den, and talked open defiance to him, in the vain hope that he would insist on an inquiry, or lay a charge against them. We must make the best of the R.A.M.C., but we surely need not be burdened with Porter’s sins. After having heard and seen something of the awful bungling of the wounded transport arrangements, one wonders how it is possible that the War Office should regard with complacency the prospect of leaving this man the very difficult work of getting sick and wounded from the peninsulas during the winter. The only reason I can think of is that professional soldiers stick to each other through thick and thin.

This unfortunate expedition has never been given a chance

I hope I have not made the picture too gloomy. I have great faith still in the Englishman. And, as I have said, the enemy is having his own troubles too.

But this unfortunate expedition has never been given a chance. It required large bodies of seasoned troops. It required a great leader. It required self-sacrifice on the part of the staff as well as that sacrifice so wonderfully and liberally made on the part of the soldiers. It has had none of these things. Its troops have been second class, because untried before their awful battles and privations of the peninsula. And behind it all is a gross selfishness and complacency on the part of the staff.

Much more I could tell you, but my task is done, though I shall write again next mail — I hope with better news.

This of course is a private letter, but you will show it to George Pearce and Hughes, so I shall say nothing more than the plain goodbye of a friend.

Sincerely yours.

K.M.

* After the Murdoch Gallipoli Letter was published, opinion turned strongly against the campaign and the troops were evacuated in December and January. Keith Murdoch later reported from the Western Front before continuing a post-war career in newspapers. His son, Rupert Murdoch, is the executive chairman of News Corporation.

‘Prisoners in their own homes’: Grim price of drive-by shootings

A victim’s advocate has called for harsher sentencing for contract shootings as the fear invoked by random attacks has gripped some Sydney suburbs. See the hot spots on our interactive map.

Who Owns Tassie’s farms: Biggest investors, landholders named

An annual investigation can reveal Tasmania has been a key destination for capital in the race to invest in Aussie agriculture. See the full list.