THE fear. The shame. The desperation.

The hunger…

There are few stories of early Australia more chilling, more viscerally gripping, than that of the Cannibal Convict.

A bunch of escaped prisoners struggling through the near-impenetrable Tasmanian forest, rations gone, reduced to picking each other off for food; the fear and mistrust around the campfire each night as nobody dares to fall asleep, convinced they will be murdered and consumed if they let their guard down; and the terrifying pursuit as two make a break for it and the others give chase.

It all happened. Yet the sole survivor, when finally caught, was not believed; the authorities thought it was all too far fetched.

Until he did it again.

That survivor was Alexander Pearce, branded by history as the Cannibal Convict, although he was one of eight.

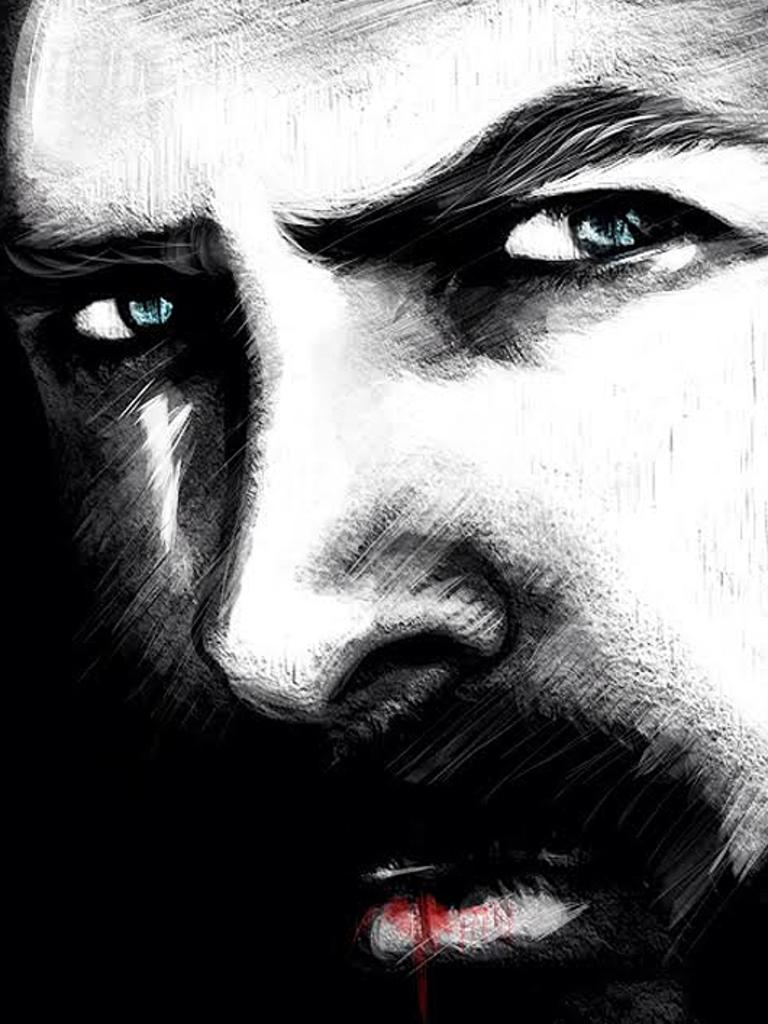

Pearce is a short, blue-eyed Irishman in his early 30s. He is to become a true criminal monster, but his initial misdemeanour is pedestrian: stealing six pairs of shoes, for which he is sent Down Under for seven years.

THE LASH HAS NO EFFECT

Shipped to Van Diemen’s Land (Tassie) in 1820, he is assigned as a servant — but stuffs up this relatively cushy assignment by boozing, thieving and absconding for months at a time. The lash has no effect, so a tougher punishment awaits: Macquarie Harbour, one of the harshest penal settlements in Australia.

This place, on an island in a bay surrounded by a mountain wilderness and hundreds of miles from other settlements, is a dumping ground for the worst of the worst. Little wonder so many long to escape, however impossible.

Pearce doesn’t just wish; he does. Spotting opportunity in the form of an open boat while working on a labour gang, he and seven others leap in, power to the mainland and dash off into the trees, seeking freedom.

What they find is hell.

The motley crew — highwayman, ex-soldier, forger, sailor, two Irishmen, a repeat absconder and a little-known eighth — have little food and less equipment.

Their ambitious plan is to head east cross-country, steal a ship and head home. But, in the words of Fatal Shore author Robert Hughes: “Before them although they did not know it, lay some of the worst country in Australia.” Mountains clad in dank, impenetrable forests that are a no-go zone even to today’s well-equipped bushwalkers.

The rations soon go; the men battle on for a week; but with no sign of breaking through to the clearer country, things quickly become bleak. The are weak, starving; team spirit vanishes, replaced by petty alliances and the instinct for individual survival. They cannot even agree to build a campfire together, instead scraping up pathetic individual blazes.

THE ONLY QUESTION IS WHO?

It is in these depths of despair that the taboo begins to crack. Here we turn to Pearce himself.

“We were very cold and hungry, Kennelly said he was so hungry he could eat a piece of a man,” he recounts later. “Greenhill … said that he had seen the like done before, and that it tasted very like pork.”

That was it. As four of them debate, then decide upon, their hideous course — agreeing they must all play a role to be “equally guilty of the crime” — the only question is … who?

The first victim is former soldier and perjuror William Dalton, allegedly because he had colluded with authorities back at prison.

“About 3 o’clock in the morning Dalton was asleep,” says Pearce. “Greenhill got up, took an axe and struck him on the head with it, which killed him as he never spoke afterwards. Travers took a knife, cut his throat with it, and bled him, we then dragged the body to a distance, cut off his clothes, tore his inside out, and cut off his head, then Mather, Travers and Greenhill put his heart and liver on the fire to broil, but took them off and eat them before they were right hot, they asked the rest would the have any, but we would not eat any that night. Next morning the body was cut up and divided into equal parts.”

THE LAST BONDS OF HUMANITY ARE SHED

The trek into horror continues.

Next day, two of the group — aghast at the cannibalistic murder — make a break for it, lagging behind then vanishing into the trees. Pearce acknowledges that if the men, James Brown and William Kennelly, make it back to Macquarie Harbour, their story will “hang us all”. But nature does its job. When found by search parties, the two are dying of exposure and starvation — pieces of meat still in their pockets.

A human body doesn’t last forever. And back in the interior, the five escapees soon need to eat again. The next to die is Thomas Bodenham, axed as he rests by the fire. Then, some days later, Scottish baker and forger John Mather — chillingly aware of his fate after the bloodthirsty sailor Robert Greenhill fails in a sneak attack.

Over to Pearce:

“I went to a little distance after we stopped and on looking round saw Travers and Greenhill collaring Mather, who cried out ‘Murder!’ When he found they were determined to have his life, he begged they would give him half an hour to pray for himself which was granted, and a prayer book given to him, which we happened to have with us. When the time was expired he returned the prayer book to me, and laid down his head. Greenhill immediately took up an axe and killed him.”

You can almost feel the hideousness as the last bonds of humanity are shed. In a sickening irony the men have finally smashed through to magnificent open grassland, teeming with kangaroos and emus — but weak, and with just one axe, they are unable to catch any game.

Travers dies next. His foot becomes infected and he bravely tells the others to leave him behind as he is a hindrance. They agree, but take him with them nevertheless — in ration-sized portions.

DANCE OF DEATH

Then there are two; and as the remains of Travers diminish, so begins the final, macabre dance of death. Neither accomplished axeman Greenhill (who has the only weapon) nor “blood-boltered goblin” Pearce (to borrow Hughes’ description) trusts the other; they walk apart and spend their nights in frantic, delirious unrest — unable to fall asleep, for fear they will wake up as breakfast.

It’s a waiting game. Who will falter first?

Greenhill. One night he falls asleep near dawn. It’s over within seconds as Pearce grabs the axe, strikes and prepares his next meal.

And finally the Cannibal Convict’s “luck” changes. Some days later, his food gone, he is close to suicide, when he comes across an abandoned aboriginal camp, with game still on the fire; he then catches wild ducklings; and finds a flock of sheep, where he grabs a lamb and eats it raw. He is apprehended by the shepherd — who, incredibly, turns out to be a convict who knows Pearce. He takes in the runaway and feeds him.

In the grubby, wilderness community Pearce falls in with two bushrangers; but with bounties on their heads (ten whole pounds) it is not long before they are betrayed and caught.

Pearce is sent to Hobart, where he confesses all — but with no surviving witnesses or bodies found, the authorities believe it is a fantastic, gory fable to cover up the successful escapes of Pearce’s fellows. He is sent back to Macquarie Harbour.

And it’s there that grotesque history repeats itself — the final chapter in Pearce’s horror tale.

Now aged 34, in November 1823 he makes second escape bid, taking along a younger convict called Cox. Within three days his taste for human flesh has resurfaced: killing Cox (apparently in a fit of rage for slowing him down), Pearce spends the next 48 hours feasting upon the body until the smoke from his campfire is spotted and he is caught once more. Sickened searchers find Cox’s mangled body, which according to one official the Irishman describes as “the most delicious food.”

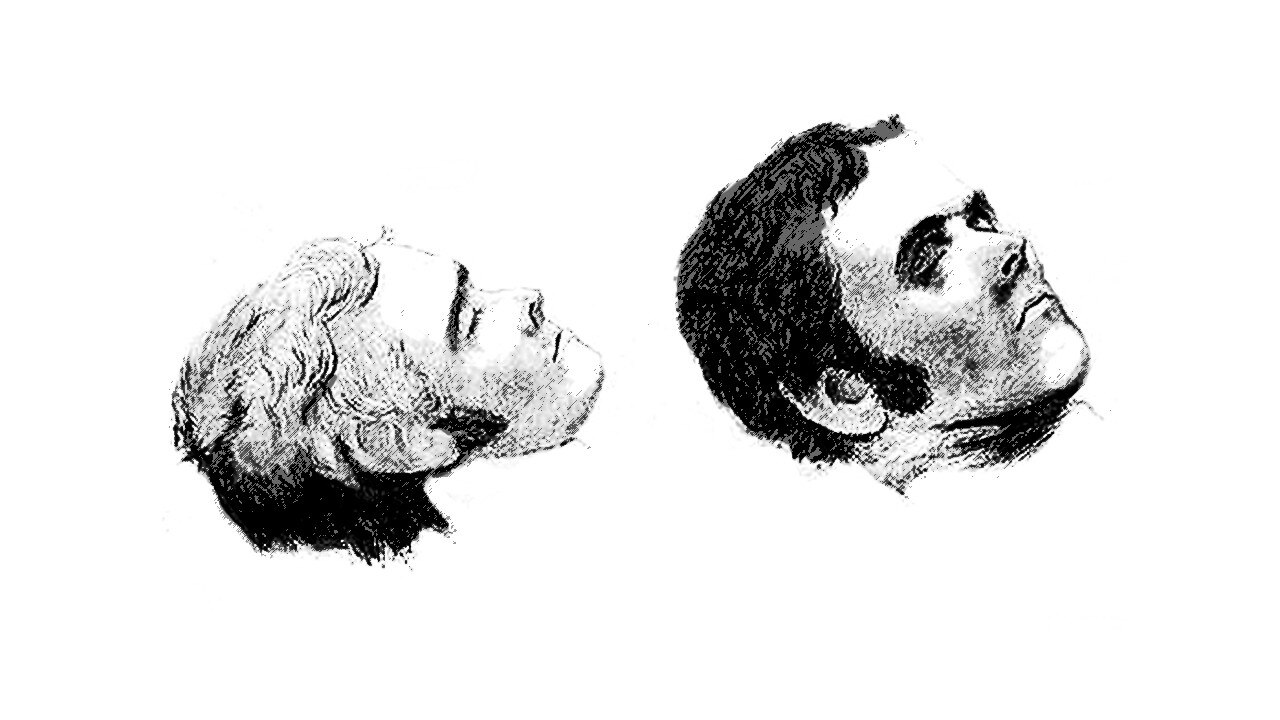

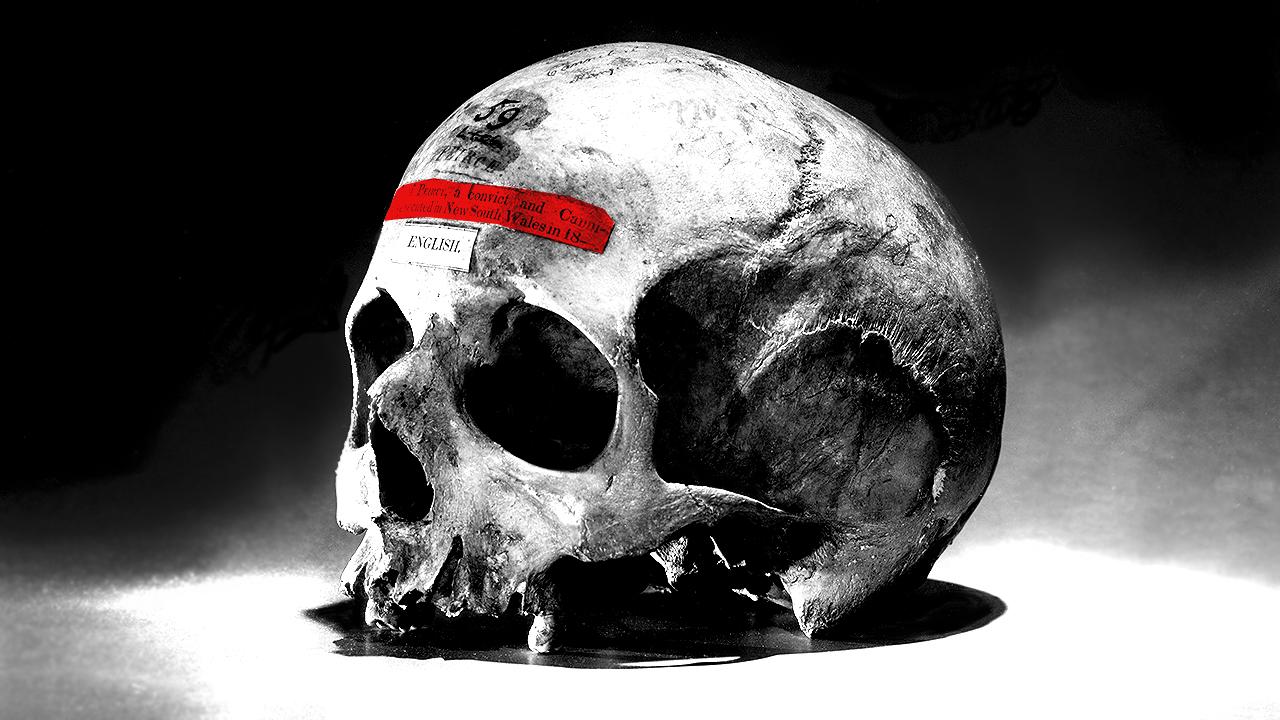

No third chances. Pearce is shipped to Hobart, tried and hanged; his body dismembered for anatomical science. His skull is boiled, defleshed and some years later given to an American quack scientist. It now resides, a neat label stuck to the forehead, in a collection at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences — a grotesque reminder of convict Australia’s most blood-curdling episode.

‘THE MOST HARDENED OF THE MOST HARDENED’

And what can we make of Alexander Pearce today? What sort of a man — or monster — was he?

“He was the ultimate survivor,” says Elise Edmonds, senior curator at the State Library of New South Wales — where Pearce featured in an exhibition recently.

“He was the most hardened of the most hardened, determined to survive at any cost.”

It is apparent from his early days Down Under that rehabilitation was never part of Pearce’s gameplan — “the lash had no effect” — and he was set on doing things his own way.

“Not that it’s something to look up to,” adds Edmonds.

Was he evil? That’s a hard one to judge from almost two centuries away.

One might argue that in his first escape he was just surviving in any way possible. Does the end justify the means? Come the second escape, however, he appears to have become unhinged.

Edmonds points out that one of the most interesting — if less sensational — aspects of the story is that “ordinary” Australians of the time simply did not believe it. Men eating each other? Surely not.

“It was beyond comprehension,” she says.

In many ways, it still is.

• This story was first published in November 2015.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer moves towards autumn what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer moves towards autumn what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.