PLANTS on Prozac? $50 bargain-bin bottles of wine? Weekly ravioli rations? The heat is on to feed a world of 11 billion people. So far research breakthroughs are keeping pace — but only just.

Agricultural science has been in a sprint since the 1960s: Better harvesters, fertilisers, pest control, crop rotation … all are ongoing developments which have kept food in the mouths of a world which has bloated from 3 billion to 7 billion in just 50 years.

But there’s a new threat to our food security: frequent weather extremes.

Our food crops are already showing signs of stress. And it’s only going to get worse.

And then there’s the price of protein. Do you buy as much fish as you used to?

What can be done about it?

SPECIAL FEATURE: Can you stomach bugs? It may soon be the only cheap meat

As politicians and business bicker about budgets and hockey stick charts, Australia’s research scientists are working urgently on problems they know are already affecting us all: It’s just most of us don’t yet realise it.

Largely, that’s thanks to the success of their efforts.

Enjoying cheaper, higher-quality wines? This is because we now understand how higher-than-average temperatures are forcing our grapes to be picked three weeks earlier than usual.

Like the price and availability of all those different pastas? This is thanks to the crossbreeding of key genes into wheat to reduce its sensitivity to increasingly salty soils.

But much more needs to be done.

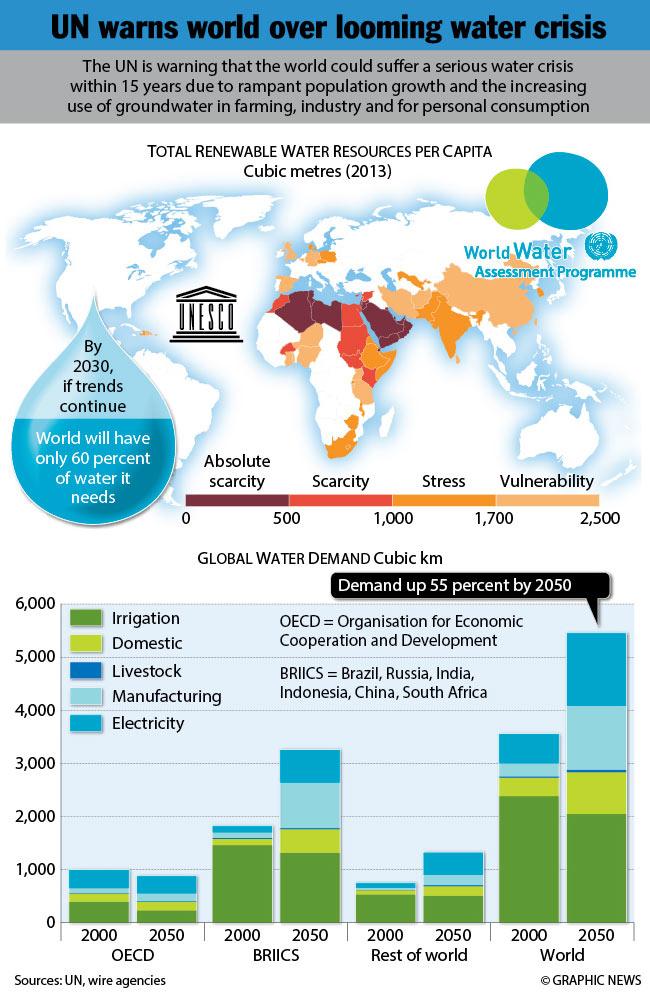

There’s a perfect storm looming as increased demand, hard-worked soils and climate-stressed plants combine to challenge our farmers.

Fortunately, a slew of advances are already in the pipeline. Some sound like science fiction:

Plants on Prozac? Yes, there may be ways to soothe the way plants react to extreme events such as frosts.

Surgical-strike pesticides? Yes, the heavy collateral damage done to innocent bystanders — such as monarch butterflies when a field is ‘nuked’ by even natural pesticides — may soon not be necessary. Instead, specific pests could be targeted with laser-like accuracy.

Talking to plants? Yes, there may be ways to warn our crops to brace for an impending heatwave.

In every case, it comes down to a significantly improved understanding of the natural processes involved.

How do our vines work? What keeps grain healthy? How can we trigger their natural mechanisms to respond to our increasingly unnatural conditions?

That’s what scientists such as those at the University of Adelaide’s School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, as well as the school of Global Food Studies, are working on now.

They say we won’t be going hungry — or without our favourite drop of red — any time soon. But only if they can keep finding new ways to stay ahead of the heat.

There are many hurdles in feeding 11 billion people. That’s the world’s projected population by the end of this century.

Then there’s the urge to keep our fridges and cupboards stocked with our favourite foods and drinks.

“Heat, cold and flood: That’s what we’ve got to expect more of,” says Professor Stephen Tyerman of the University of Adelaide’s School of Agriculture, Food and Wine. “So we’ve got to make our agriculture more resilient if we want to keep eating.”

None of this is new. It’s just the frequency and intensity that is ramping up — fast.

We’ve already had a taste of what is to come.

Remember when the Murray River almost dried up? When our citrus orchards were being ripped out of the ground? As soon as the drought broke, food security went off the agenda.

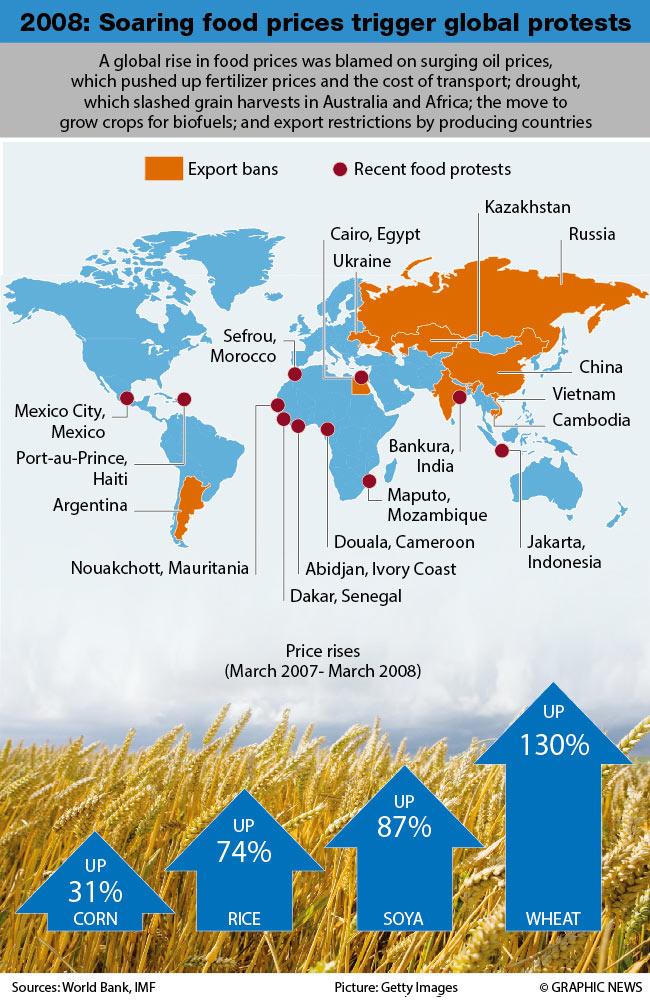

But there was a real global food crisis back in 2005-2008. It brought empty supermarket shelves and across-the-board leaps in prices.

Fresh fruit and vegetables were the worst hit with price spikes of between 30 to 40 per cent. Eggs and bread rose 17 per cent, beef went up 31 per cent and lamb leapt 59 per cent. Honey prices doubled.

We know this will happen again. It may be sooner than we think.

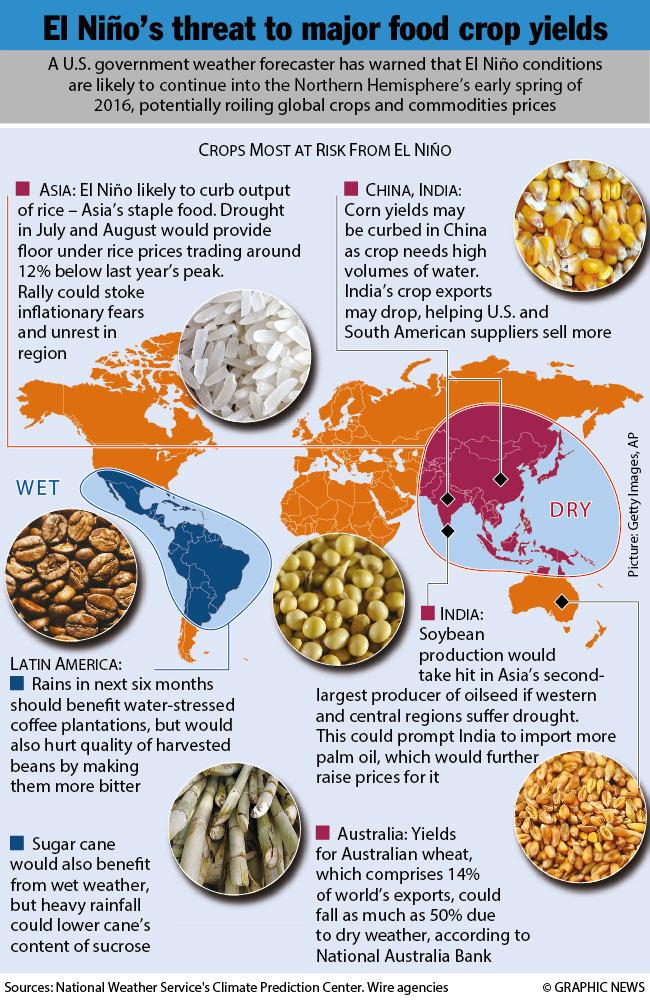

This year we’re staring down the barrel of another significant El Niño weather anomaly. The last one triggered the long and debilitating drought which contributed to those price rises.

Grain crops are especially vulnerable to dry weather. If existing trends continue, by 2070 we’ll be wrestling with 40 per cent more months of drought than now.

If grain prices go up, so does meat. Beef, lamb and poultry all require ‘finishing’ on grain-based feed.

But the canary in the coalmine may well be wine grapes. They’re among the most sensitive to climate.

What can we do about it?

Plants have nervous systems. No — not the triffid-like brains of John Wyndham’s famous book. But they do have processes which sense the environment and instruct internal systems how to react.

One such neurotransmitter is the same as found in humans: it’s called gaba.

“Basically the gaba concentrations build up massively when the plant is stressed,” says Associate Professor Matthew Gilliham of the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine. “If an insect crawls on a leaf, gaba concentrations will increase within seconds.

“That’s the thing about plants, they can’t run away and hide from a bug — they can’t seek shelter from the heat or cold. They have to sit there and tolerate whatever is thrown at them as best they can.”

The solution? Well it’s not breeding walking triffids that can fight back or move to a more convenient place.

“If we can manipulate gaba levels, we can change how the plant reacts,” Dr Gilliham says.

It’s not a matter of doping up a plant on vegetative stimulants or depressants.

It’s about talking to them in their own language.

“For example, they’ve modified a fungicide which is sprayed on to plants,” he says. “In trials it actually tells the plant to close up the stomata — the breathing pores — on its leaves to stop it losing too much water through perspiration.”

Then there’s killing damaging bugs and fungus, with sniper-rifle accuracy.

It’s not about DNA. It’s about using the tools DNA naturally produce. Collectively, they’re called RNA.

“Our bodies are made up of DNA, it’s our library, it’s our code,” Dr Gilliham says. “A rough analogy is that DNA is the computer and RNA is the 3D printer which produces specific proteins for specific purposes.”

These RNA ‘printers’ fragment — or wear out — at a predictable rate to ensure the right dose of proteins is delivered. Introducing fragments of specific RNA can influence the amount of proteins produced. This can be a matter of life or death.

The application? Extremely safe pesticides tailored to a specific beetle or fungus.

“It’s a non GM technology, it’s not introducing anything novel to the food chain — it’s using what’s already in everything,” Dr Gilliham says. “So this spray may target a beetle which feeds on rape seed, but it won’t kill off the monarch butterfly at the same time.”

Australia’s vine growers are having to find new ways to cope with huge changes from year to year.

“We’re already getting seasons that will be the average in 30 years’ time,” says Professor Tyerman. “We’ve been able to adapt to those differences. The problem is the extremes: That’s what is going to get us.”

What used to be a one-in-50 year weather event is now a one-in-10 year event.

“It only takes one heatwave and that just topples vines over the edge,” he says.

So, can we expect $50 bottles in the wine bargain bins in coming decades?

“I don’t think that will happen,” Professor Tyerman says. “What will happen is that the quality of wines will improve so what was $50 today will be $15.”

The challenge, however, is evident to all involved. Since 2001, the University of Adelaide has had to move its courses for viticulture students back by three weeks.

Vines now ripen much earlier than they did 14 years ago. More than three weeks earlier, in fact.

That’s a direct result of climate change.

“The harvest date for grapes in Australia has been advancing at a rate of about 1.5 days per year,” Professor Tyerman says. “The growers see that. You talk to any viticulturist; they will not deny climate change.

“But we’ve found out from our studies that we’re not powerless,” he says. “By doing the research and finding out what affects this trend we’ve seen over time, we’ve found out that it’s not all bad, that there are things in our control that we can change and adapt.”

Temperature isn’t the only ingredient influencing ripening vines. There is also soil moisture level and how many grapes burden each vine.

The implications are extraordinary.

Irrigation can now be much more accurately targeted. Research in the Riverland shows no noticeable impact on vines irrigated with half the traditional load of water. It’s just that they now know when the plants actually need it.

During extended drought, vineyards will no longer have to be ripped up. Studies show they can be ‘mothballed’ for at least four years with just 10 per cent of the water they usually need.

“As soon you go back to a normal irrigation rate, the vines are fine,” Professor Tyreman says. “We didn’t know that 10 years ago.”

“I think we can be optimistic, as long as we keep moving ahead with using our nous, using technology and actually doing all the measurements. We’ve got some successes there. And these will be needed.”

A combination of irrigation and land clearing, among other things, can make soils vulnerable to rising salt levels. And we’re going to have to crop even harder to feed 11 billion mouths.

Ten thousand years of farming has produced grain crops carefully crafted to suit our needs, he says. But, like pets, there can be problems from too much inbreeding.

So the search is on to identify fresh gene stocks to give our food varieties a boost.

“If we can increase average yield in Australia just a little, then we can make quite a big dent in food security issues around the world,” Dr Gilliham says.

Opportunities to do this are rare, and novel.

But one such opportunity came from an unusual source: an archaeological dig in an ancient cave.

“A cave in Armenia has preserved ancient grains,” Mr Gilliham says. “So this is early domesticated grain, thousands of years old. The idea is we can get into the DNA of that grain and start to look at the diversity that’s in it to find what may improve stress resilience now.”

And it doesn’t necessarily require genetic modification to inject that lost DNA back into modern plants.

All it takes is a little breeding.

“It came down to one single gene in duram wheat,” says Professor Tyerman “It was not put in by genetic modification. It was done just by crossing and breeding it in to the wheat line. It produced a 25 per cent increase in yield on salty soil, without any penalty when grown under normal conditions.”

It’s a significant victory. Many more like it are needed, and soon.

How? The recent win with durum wheat opened up a realm of possibilities.

“We’ve also put that gene back into bread wheat and we’re starting to see some interesting results there, too,” Dr Gilliham says. “The theme of our research now is trying to reclaim lost diversity.”

“We’re definitely getting the runs on the board in terms of breeding for wheat varieties that are more water efficient and salt tolerant, ,” agrees Professor Tyerman.

With such dramatic climate change, the old ways may no longer be the best ways. The goalposts are shifting, fast.

“To a plant such as barley or grape vines, C02 is their oxygen,” says Professor Tyerman. “It does all sorts of things to plants. Just in the last 50 years plants have behaved completely differently to how they have previously. They’ve changed the number of specific cells on their leaves even in that time, because of the C02.”

If we could smell what was happening with C02 concentrations, there’d be no argument

“That’s the part of the problem — we don’t notice it,” Professor Tyerman says.

It all comes down to accounting. Efficiency. Overcoming ignorance and finding new understanding.

It’s a matter of keeping ahead of the weather.

“Yeah, OK, we’re going to reach 2C if we do what we say we’re going to do,” says Professor Tyerman. “But it could go to 3C. It could be a tipping point. But we can get through it if we exploit this third wave of technologies.”

That involves government. That involves business. That involves the public.

“We can basically end up replacing Holden with assembly lines to manufacture our survival in the next century,” he says. “As explained by Professor Tim Flannery, the technology is exploding. Wind farms, for example: Did you know they have 3D printers on the actual blades fixing them as they’re being used? Gearless turbines to reduce the maintenance load? The cost of production and maintenance has been absolutely diving.”

Just as scientists strive to understand the impact of climate change on our plants, so too do politicians and the public.

Dr Gilliham is adamant.

“It’s an obligation really; it would be immoral not to try. If there’s a way to feed 11 billion people, we have to try to find it.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with today’s Parramatta weather

As winter sets in what can locals expect today? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As winter sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.