Deepfakes explained: How Australian students are using AI to target classmates, teachers

Experts and educators have lifted the lid on the reality of AI through our children’s eyes – and their take is frightening. See how they say you can protect your kids.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Teenagers are using AI to “nudify” photos of their classmates and concoct compromising “deepfakes” of teachers, while children as young as 12 are sending each other pornographic videos.

Educators and experts have lifted the lid on the shocking impact of artificial intelligence and social media, warning parents need to “have eyes in the back of your head”.

Latest figures from the eSafety Commissioner reveal hundreds of children aged 12 or younger have reported being the victim of image-based abuse, involving real or fake pictures, in recent years.

Thousands more aged between 13 and 17 have been victimised by sextortion, scams, threats and AI manipulation.

Those on the frontline warn these reports represent a fraction of the problem, which is being turbocharged by the pace of technological change and sexist influencers like the notorious Andrew Tate.

But there are signs of a fightback.

This week, UK authorities confirmed charges against Tate and his brother Tristan, including rape and human trafficking.

A ban on teens using social media will take effect in Australia at the end of the year, and new laws and industry standards are closing the net on dodgy platforms and their users.

SO HOW BAD IS AI IN AUSTRALIAN SCHOOLS?

There has been a spate of high-profile cases of students caught using AI to create, and even sell, fake images involving classmates or teachers.

In June last year, the arrest of a Bacchus Marsh Grammar schoolboy in regional Victoria made international headlines after 50 female students were allegedly targeted in fake explicit AI photos.

In January this year a senior student at a Southwest Sydney public high school was accused of creating deepfake pornographic images of female students.

Sydney private school students have also been caught selling deepfake nude images of female classmates on social media.

In May a boy at Adelaide’s St Ignatius’ College was suspended after the discovery of a deepfake image involving a teacher.

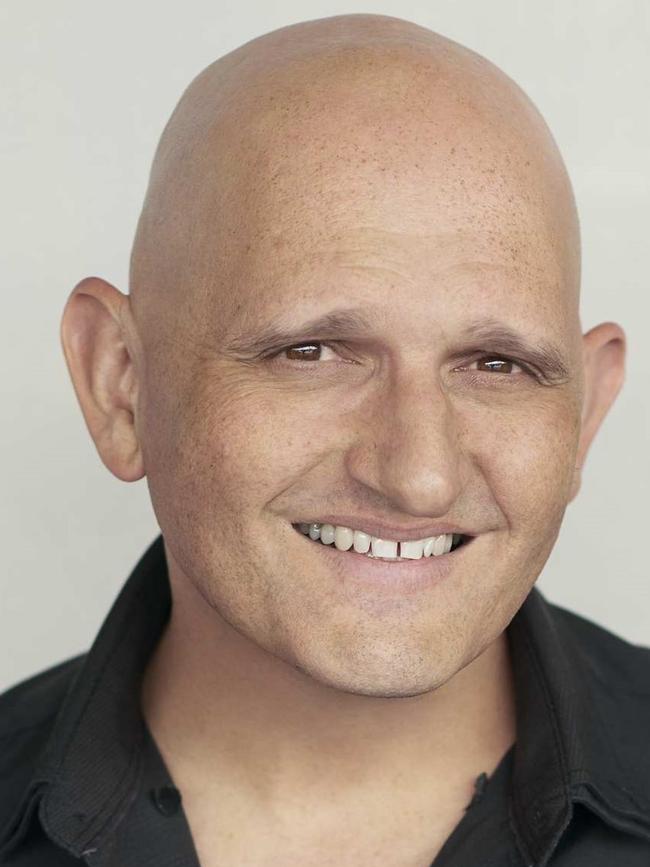

These cases are just the tip of the iceberg, says Dom Phelan who works with hundreds of students across Melbourne each week as part of the Optus Digital Thumbprint program.

This year he has been to at least six schools which have called in police to investigate deepfake images created by students.

In one case, a group of boys had made fake images of one another, Mr Phelan said.

“It started out as a bit of a joke and then went over the line. One student has since left that school because he was completely humiliated and couldn’t face his friends anymore.”

At a different school there was a trend among year 7 boys “to send pornographic videos to one another”.

Elsewhere students had used AI for “making fun (of classmates), body shaming or pointing out kids’ insecurities”.

“Kids don’t see the consequences of these things straight away,” Mr Phelan said.

“They’re not thinking of what’s going to happen down the track.”

IS THIS A NEW PROBLEM?

In short, no, but new technologies are making it easier to cause more harm.

Research by Monash University conducted six years ago found 14 per cent of 16 to 64-year-olds in Australia, New Zealand and the UK had been the victim of a “sexualised, digitally-altered image” created without their consent.

Lead author Professor Asher Flynn said the tools to create that harm had only “become more readily available and easy-to-use” since then.

“A big concern is that the rapid spread of these tools is already normalising the practice of sexualising images, particularly of women and girls, without their consent,” she said.

Recent surveys by the eSafety Commission found one in 10 kids have been asked to send someone sexual images and almost half have received one.

Australian Centre for Child Protection director Professor Leah Bromfield said greater exposure to online pornography was distorting normal sexual development.

She recently told a hearing for SA’s royal commission into domestic and sexual violence that historically young people might have snuck a peek at something like “the Bras N Things catalogue”.

“What kids are seeing (now) is really explicit sexual content. When 12-year-olds are asking ‘Is it normal for my boyfriend to try and choke me when we’re kissing?’ that’s a real problem.”

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Federal laws passed last year made creating and distributing sexualised AI-generated images an offence.

In South Australia, MPs are updating legislation to ensure humiliating or indecent content which is completely AI-generated is covered.

From June, new national standards will crackdown on tech platforms which enable users to generate explicit or illegal content, with potential fines of almost $50m.

Schools are updating lesson plans to address the risks of AI, including deepfakes.

Dr Tessa Opie, founder of inyourskin, has worked with education departments in SA, WA and the NT and told the SA royal commission students were “sick to death of the fear tactics”.

Instead they wanted practical advice, real-life examples and interactive discussions.

“They don’t want to talk about it in ways where they glaze over before the lessons even begin,” she said.

In December Australia will enact a world-leading ban on under-16s using social media.

University of Melbourne’s Dr Gemma McKibbin said it was “really important that parents actually support that”.

She acknowledged it was “tricky to know what is really going on” with young people but urged parents “to have very brave and open conversations with your children”.

More Coverage

Originally published as Deepfakes explained: How Australian students are using AI to target classmates, teachers