South Australian Alex Mericka tells father Jan Vladimir Mericka’s remarkable story on International Holocaust Remembrance Day

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Alex Mericka wants the world to know the truth about his father – a truth he didn’t know until his late 30s.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

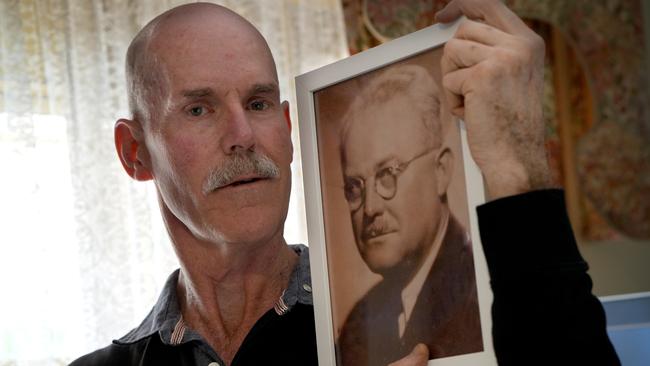

Alex Mericka spent half his life believing his late father Jan Vladimir Mericka was a Nazi, and today, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the 68-year-old is keen to set the record straight. Alex wants to tell his father he understands why they only ever saw each other a few times – and despite that, why he is still a hero in his son’s eyes.

The truth is that Mr Mericka’s father and grandfather, Jan Aldricht Mericka, helped dozens of Jews escape Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, nearly paying for it in blood.

Estranged from his mother, Sheidow Park retiree Alex only discovered this in 1991 when his stepbrother posted him a recording of Vladimir’s final testimony, before his death a few years earlier.

It arrived with a black-and-white portrait of his father, a distinguished Prague accountant, and grandfather Aldricht, a lawyer dressed in his Sunday best.

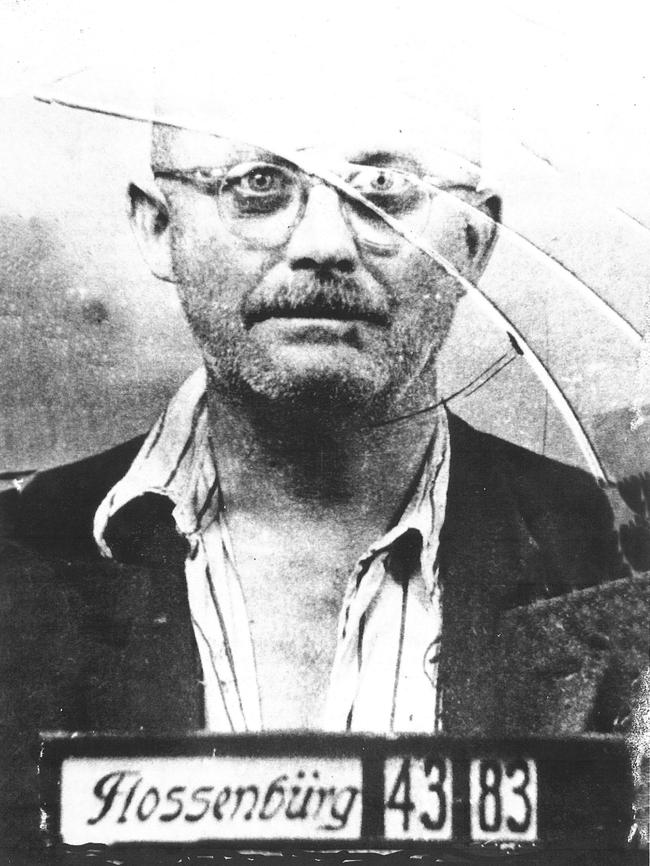

There was another photo of his grandfather from 1943, sans necktie, eyes bulging, standing behind a placard labelled “Flossenburg” – the concentration camp where approximately 30,000 people died.

How did Mr Mericka – an ex-Army reservist, heavy machinery driver, and now neighbourhood clean-up volunteer – react to this?

“I never thought too much about it at first … there was a lot going on in my life,” he told The Advertiser.

“Since my parents divorced in the fifties, my mother did everything she could to stop my brother, sister and I from knowing our dad.

“She said he used to beat her and that when I was two, he shot our pet dog … apparently, to teach us that we can’t always keep what is dear to us.”

Decades later, Mr Mericka is unsure what to believe, but it does not square with Mr Vladimir’s life in his own words.

Thanks to Aldricht’s law practice, the Merickas owned “quite an estate”, with livestock, cherry trees, and a vineyard that produced “the preferred wine of the Austrian officers’ mess”, according to Vladimir’s recording.

“They would frequently send out a truck to collect an order … certainly at the time, it was something my father was very proud of,” Vladimir said.

“Many times my father succeeded against great odds to bring about a just verdict … nevertheless, farming was in his blood and he yearned for the environment of a farm.”

The Gestapo took everything when they arrested Aldricht, who was using contacts in the Ecuadorean embassy to secure visas for Jewish clients unable to flee Europe.

“To my father this situation was twisted and wrong … (he) knew what he was doing was against the interests of the Nazis,” Vladimir had said.

For helping the plot, he himself was sent to Dachau extermination camp in 1944, being forced to move executed prisoners’ bodies.

Vladimir claimed he and others foiled Nazi executions with a scheme that involved swapping murdered prisoners’ dog tags with those still living.

He remembered trying to convince three captured US spies to go along with the ruse: “Two of the Americans accepted … the other fellow persistently argued with me, telling me he would go to the camp commandant and tell (him) about the fact his father was ‘a rich Boston newspaper owner known worldwide’ … He insisted that the commandant ‘would not dare have me shot’.”

According to the recording, the spy was killed the next morning, while the other two survived, and the Allies liberated both camps in 1945. Aldricht “mysteriously died” shortly before the Communists took power, and fearing his fate, Vladimir fled to Australia with an aristocrat countess’s help.

Alex transcribed all of this, knowing the day would come when someone would care.

But life got in the way, including a debilitating spinal injury at work, and an ensuing compensation dispute forced him to spend thousands of dollars and countless hours trying to win a fair claim.

Now battling prostate cancer Alex in late 2024, approached the Adelaide Holocaust Museum to admit his father’s testimony into their records.

He is now working with researchers to see what other footprints the pair could have left behind.

“Throughout my life, I’ve always had this desire to help people, and I never really understood where it came from,” Alex said.

“It’s important we remember what happened to the Jews, but that there were people out there who wanted to help and were punished because they saw what was wrong … I want to make sure that everybody knows that.”

“I wish I could take back those years because I felt like I should have known him better,” he said.

“If he did all those things, why couldn’t I do something for him?”.

More Coverage

Originally published as South Australian Alex Mericka tells father Jan Vladimir Mericka’s remarkable story on International Holocaust Remembrance Day