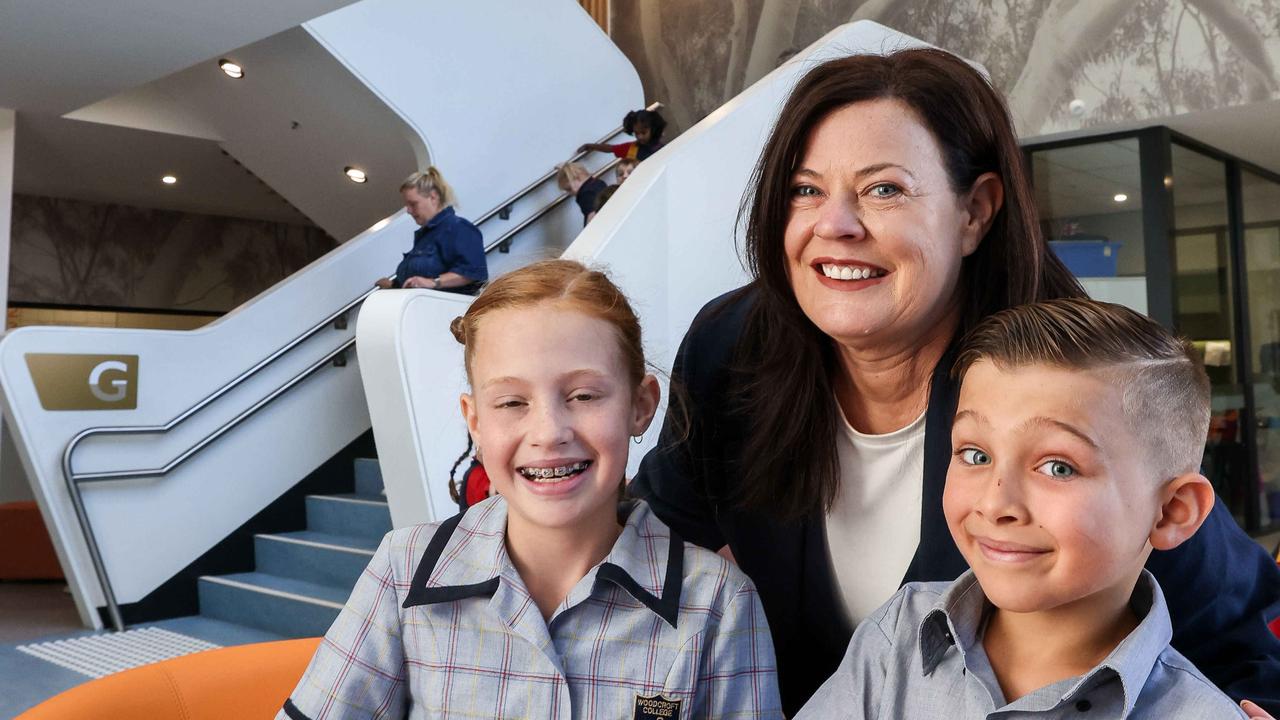

Adelaide Fringe director Heather Croall credits Whyalla upbringing after 10 years in festival’s top job

The boss of the Adelaide Fringe says if it wasn’t for her upbringing in Whyalla, the event wouldn’t be as big as it is today.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For a young Heather Croall, growing up in Whyalla in the early 1970s offered not only economic opportunity and career potential, but a thriving world of arts and culture.

It set her on a path of creativity and innovation which, five decades later, finds Croall about to deliver her 10th annual program as director of the southern hemisphere’s largest arts festival, the Adelaide Fringe, which runs until March 23.

During her tenure, the event has grown, survived a pandemic which limited overseas and interstate acts, and refocused its agenda to support artists through funding programs to develop new works and ticketing systems which return more money to acts.

“Whyalla was on the circuit for the arts – we used to have (French puppet company) Philippe Genty, bands would tour … (comedian) Billy Connolly as well,” Croall, now 58, recalls fondly.

“We had a lot of access to arts, there was a lot of regional touring. And we definitely had a mum who encouraged us to be part of the arts.”

When Croall was about three years old her family moved from the UK, where she had been born in the seaside resort town of Blackpool to Scottish parents.

Her late father was a gynaecologist/obstetrician and Australia at the time needed specialists, who had their pick of where to settle.

“He was brought up in Glasgow, in the rain,” Croall says.

“They said you can live wherever you want – they offered him Byron Bay and Hobart and places in Queensland. Every time they took him somewhere, he said: ‘How often does the sun shine here?’ When he got to Whyalla, they were like: ‘Every day – it never rains.’

“So we could have gone anywhere, but we went to Whyalla. It was a good town to grow up in, with freedom. It was a great, thriving town, there was no unemployment – everyone had a job at the shipyard or the steelworks – and there was a very young population. There were like 12 primary schools.

“So I had a great childhood in Whyalla and my parents loved it – my dad stayed there until the day he died.”

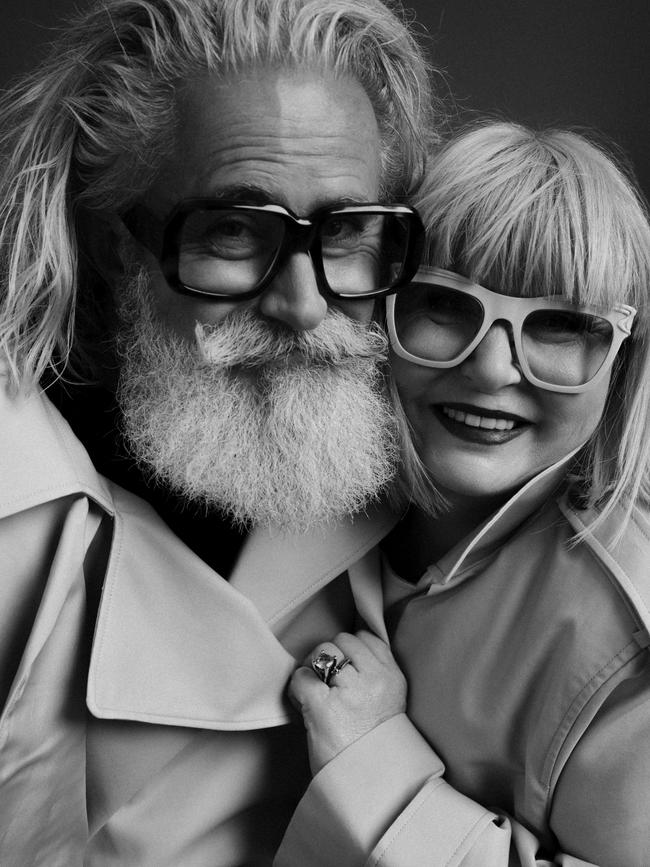

Over the course of eight years, Croall made the documentary Yer Old Faither – a Scottish term for father – exploring his relationship with the city, which Heather says is also a “character” in the film. It won the audience award at the 2020 Adelaide Film Festival.

“My dad set about planting trees in Whyalla in his spare time. As a child, I used to have to travel in the back of the car with him, with buckets of water and stuff, every day. It seemed ridiculous at the time, but now when I go back to Whyalla, there’s 10,000 or more trees – fully grown – that were planted by him. It really changed the whole landscape of Whyalla.

“He was a pretty eccentric, Scottish man in the desert.”

Last year, Croall had to undergo surgery to remove a melanoma on her shin, which required a skin graft. It was discovered during an annual check, which she does because of her “Scottish skin” and childhood exposure to the sun.

“I didn’t even see it – it was just a little freckle. But everyone should go and get their skin checked,” she says.

While studying communications at the Magill campus of what is now Uni SA, Croall’s lecturers included Shane McNeil, who also taught film students at Flinders University.

“He did a documentary production strand, so I signed up for that – and that was it. I just absolutely loved documentaries,” she says.

Funded by the former Film South organisation, Croall made a film about surfers at Cactus Beach, which was bought by SBS and set her career in motion.

With producer Alison Elder, she also accidentally raised the ire of car company Volvo after making a funny short film about its drivers and entering it in a national competition.

“It was a love letter to Volvo drivers, but it was a comedy,” Croall recalls. Funnily enough, enthusiasm from the judges, it didn’t win.

Later, while making documentaries for UNICEF in the South Pacific, Croall was introduced to the Fa’afafine – men who are raised and identify as female, and are traditionally recognised as a third gender – in Samoa, which led to her 1999 film Paradise Bent.

Throughout her career, Croall has also kept a foot in the Fringe. In the early 1990s, she managed the Star Club adjacent to the Lion Arts Centre for comedy promoter John Pinder, while making TV documentaries for his wife.

Croall continued to make documentaries for TV both here and in the UK, but says it “wasn’t really a way to making a living when you’ve got two kids, and so on”.

In 1994, Croall was also involved with Shoot the Fringe, a project where participants were given rolls of Super-8 film to record their experiences at the event, which were subsequently projected on walls at the Lion Arts Centre courtyard. By 2000, Croall became the director of the Australian International Documentary Conference in Adelaide.

Then in 2002, Croall ran the Fringe’s film and digital component. She was instrumental in bringing British new media group Blast Theory to the 2004 event, for which it created I Like Frank, the world’s first 3G mixed reality game, where phone users in the real city of Adelaide chatted with players in a virtual city as they searched for the elusive title character.

“It was all about how we could bring interactive technology all through the city as a gamification experience.”

Around the same time, Croall had been the industry programs manager for the SA Film Corporation, which included development of its new digital fund.

“I was very into that cutting-edge intersection of film and technology, and early days of interactivity. We set up a whole program around games and film.”

Working simultaneously with the SA Film Corporation, the Documentary Conference and the Fringe, Croall helped build connections between the screen, technology and gaming industries which are now seen as crucial.

“A lot of what drove me in that era was that I wanted to make the documentary festival that I wished had existed for me as a producer, the great marketplace where you could meet all the funders and have the distributors and the commissioning editors and investors.”

Croall took her “Meet Market” concept with her to the Sheffield DocFest in the UK when she was appointed as its director from 2006-14 – initially unaware that she was returning to the city where she had lived as a toddler until her family moved to Australia.

“I have zero memory of living in England when I was little, because I left when I was like, three. When I got the job to be the director of the documentary conference in Sheffield, my dad said: ‘Oh, you’re going back to the beginning.’ I was like, ‘What do you mean? I’ve never been to Sheffield.’ But of course, you don’t remember much when you’re two or three.”

During her tenure in Sheffield, Croall continued to produce about 10 documentaries for the BBC.

“It’s more of a passion/love kind of project for me. The parallel lines of what I always did were making films, working in the Fringe, but also being very interested in working with people that are bringing games design and things like that into traditional screen storytelling.”

Croall says there have been two sides to her “digital transformation” of the Fringe over the past decade.

The first was about rebuilding its systems for how customers and artists engaged with the event, in terms of ticketing and registration.

“Separate to that was the idea that we would bring interactive programming in as a genre. Linked to that was a lot about trying to get new audiences in … people that might not want to see a traditional performance but they do want to do an immersive, promenade-style game on the street.”

Croall had adopted a similar approach at the Sheffield DocFest, where people also initially questioned the presence of gaming developers.

“Now it’s almost impossible to find a film festival in the world that wouldn’t have interactive as part of their programming.”

Adopting the Red61 ticketing system used by the Edinburgh Fringe in Scotland, the Adelaide Fringe worked with local web solutions company Catalyst to build its new customer interface, and develop its own registration system to match up artists and venues.

Elements of those online platforms have since been used by other events, including South Australia’s History Festival and Perth’s Fringe World.

The Fringe began as a way to present SA artists and companies which weren’t included in the first international Adelaide Festival of Arts program in 1960. While it has since grown to more than 1300 acts annually, the large number of professional interstate and international performers and promoters has increased competition for SA acts to find an audience.

Croall says international acts have been a strong component of the Fringe for more than 30 years, but that local acts have held their own.

“South Australia dominates in the top 50 selling shows. In the 1200 or 1300 shows that happen at Fringe every year, around about 750 are South Australian – 55 or 60 per cent. About 30 per cent might be from interstate, and about 15 to 20 per cent are international.

“Ticket sales for South Australian shows do really well. The whole thing of word-of-mouth is a big part of the ticket sales in Fringe.

“It doesn’t mean everyone sells well. There are hot spots and cold spots, and that happens even in a small festival of 20 shows. Sometimes a show just doesn’t take off.”

For the past seven years, the Fringe has operated a philanthropic arm where the public can donate, and received funding from the state government to give grants to SA artists.

“We use the donations and funds from the state government to make sure that emerging artists can still be part of Fringe. The grants that we give out help keep the Fringe diverse … and inclusive and accessible. The first year, I think we gave out $30,000 … we’re giving over $1m in grants out now, to 230 shows.”

Around 400 “buyers” from 36 countries also attend Fringe’s marketplace, shopping for acts to program at other festivals, theatres and arts centres, and even cruise ships.

“Artists are doing the Fringe for a lot of different reasons,” Croall says.

“Some of them are doing it for box office, some are doing it for fun, some are doing it to get discovered and booked on a tour from the marketplace.”

By refocusing on building audiences for shows, instead of free public events like the former parades and parties – which have largely been replaced by the opening of parkland hubs like the Garden of Unearthly Delights and Gluttony – the Fringe has been able to lower its ticketing fees for artists from around 14 per cent to five per cent.

The Fringe is an open access event, which means that anyone can register to take part, but they do so at their own financial risk – unlike the main Festival, which selects and pays its artists directly to perform.

“We have to focus on selling tickets for the artists and maximising their payout from the box office,” Croall says.

“Adelaide Fringe doesn’t keep the box office. A lot of people don’t understand the mechanics of how we work. We don’t keep the ticket money – we pay it to the artists and the venues. It’s what we exist for.”

Last year, the Fringe paid $26m to its artists and venues.

“Then they come back,” Croall says. “If we hadn’t made those changes … we would have lost a lot of artists. We’re constantly listening and trying to improve.”

To build ticket sales, the Fringe must also build its audience numbers, something that cannot rely solely on Adelaide’s limited population. Croall says it has particularly focused on attracting visitors from the eastern states.

“We know that tourists, when they come here, are going to spend more time seeing more shows. They don’t have to go to work nine-to-five, so they are devoted to being out and about.

“When I started, we had about 10,000 tourists and on average they were staying one-and-a-half nights. Now we’ve had 58,000 tourists, staying on average five or six nights.

“That is massive. It’s massive for the hotels and the restaurants, but it’s (also) huge for the shows – they are going to see five or six shows.”

Of the million Fringe tickets sold last year – double the number of a decade ago – about 300,000 were bought by visitors from interstate and overseas.

“Ten years – it’s pretty wild,” says Croall.

“I’ve got lots more energy in the tank to do a lot more growth at Fringe, particularly around getting more audiences in, getting more tourists in.

“I want many more interstate people to discover that Adelaide Fringe is the best event in Australia.”

Program and bookings: adelaidefringe.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as Adelaide Fringe director Heather Croall credits Whyalla upbringing after 10 years in festival’s top job