Patrick Carlyon: Cardinal George Pell faces biggest fight of his life

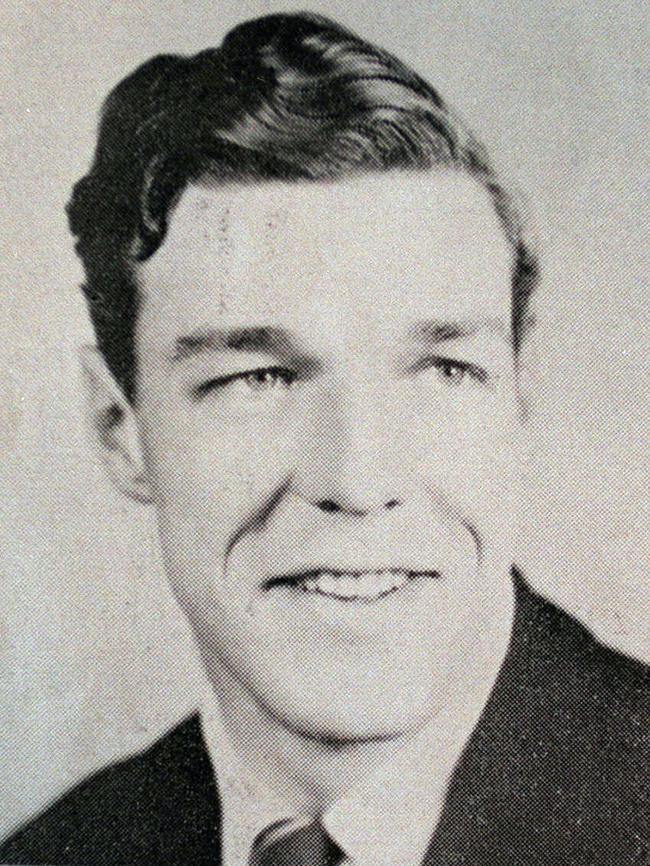

CARDINAL Pell is in uncharted territory. He now faces a criminal court — not a church or parliamentary inquiry — where he will be George Pell, 76, of Rome, writes Patrick Carlyon.

Patrick Carlyon

Don't miss out on the headlines from Patrick Carlyon. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Cardinal George Pell charged with sex offences

- Cardinal George Pell unlikely to return to Vatican City

- Pell accusers are ‘over the moon’

- Andrew Bolt: What hope does Pell have of fair trial?

- Susie O’Brien: Senior Catholics are not above the law

- George Pell scandal timeline: How the extraordinary events unfolded

IF Cardinal George Pell once got to pick his fights — from the scandal of abortion to the sins of homosexuality — he has since learned to open new battlefronts in response to hostilities aimed at him. Pell may be an Oxford scholar, but he is also a student of Sun Tzu.

His response when the Herald Sun first revealed the details of a police investigation in early 2016 was a tone of outraged denial of “baseless” allegations.

Yet Pell’s office went further — Pell demanded an investigation into the leak of the police investigation.

Pell adopted a similar approach when a book was released last month.

Pell’s office responded in the long established tone — imperious, outraged and unambiguous.

“Each and every allegation of abuse and cover-up against him is false,” it said. “The book is an exercise in character assassination.” Pell would launch defamation action.

First, he would await “the outcome of due process”.

On Thursday — after a protracted game of back and forth between police and the Office of Public Prosecutions — the police laid criminal charges. Due process is now about to begin in Melbourne Magistrates’ Court.

WHAT PELL CHARGES MEAN FOR THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

It’s another involuntary leap for a powerful figure whose clamp on his public agenda first loosened in 2002.

At the time, when allegations of abuse against him were aired — and subsequently dismissed by a retired Supreme Court judge in a church-constituted inquiry — Pell spoke of being “exonerated”.

Pell has since appeared at a parliamentary inquiry, and repeatedly at a royal commission, before an audience of abuse survivors who reflexively hiss, howl and heckle.

He has always fronted these forums as a church leader.

The questions and criticisms pertained to his responses to sexual abuse.

Thursday’s developments are uncharted territory, as the cardinal now faces a criminal court, not a church inquiry.

The allegations demand public scrutiny of Pell’s own history.

The Vatican’s Prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy, and a Companion of the Order of Australia, will be obliged to leave these and his other titles alongside the metal detectors at the door of the William St complex.

Here, he will be George Pell, 76, of Rome, versus the Crown.

Armed with one of the best QCs in the country, he will engage in the biggest fight of his professional and private life.

In the 1990s, Pell — then archbishop of Melbourne — instituted his Melbourne Response, a capped compensation scheme for church abuse victims.

In 2002, Pell commanded the blind support of public figures from then prime minister John Howard down. They did not need to test the evidence when a middle-aged man floated long-ago allegations of sexual offending.

Back then, Pell felt free to catalogue society’s sins, from same-sex unions to contraception, untethered from the paedophilia rot within his church.

At the time, he said that abortion was a “worse moral scandal than priests sexually abusing young people”.

Attitudes have changed — Pell himself has admitted as much.

On Thursday, public leaders mumbled pronouncements about presumptions of innocence and the course of justice. They played safe — Pell, after all, is the biggest Catholic figure in Australian life since Melbourne archbishop Daniel Mannix, whose statue stands outside St Patrick’s Cathedral.

Pell has been a moral talisman for conservative leaders and an emblem for a besieged church — as such, he has doubled as a bullseye.

He was long detested by elements within the church, including his predecessor as Melbourne archbishop, Frank Little, in death labelled (by Pell, among others) as a protector of paedophile priests.

Pell’s career, at home at least, has been rocked by allegations of systemic church cover-ups.

His foundation story speaks of a pub upbringing and footballing prowess, and a cheery way with kids.

From Ballarat, this point of fact unpicks any easy telling of Pell’s life. Ballarat was the cesspit of priestly paedophilia. Pell lived for a time with Gerald Ridsdale, the former priest who exploited his trusted position to become one of the most shameless abusers of children in modern history.

Pell has always maintained that he did not know. What he did or did not know, and what he ought to have done, are the kind of provocative questions that offer Lindy Chamberlain-like barbecue appeal.

Under questioning, he has blamed errant individuals, such as Little and Ballarat bishop Ronald Mulkearns, for the perpetuation of paedophile scandals. Bad people, it was, not bad systems.

Pell himself was guilty of nothing, he seemed to say, except hopeless incuriosity born of vaulting ambition.

Until Thursday, Pell was ostensibly an observer and facilitator in the process of knowledge and reform.

He framed his role as protector and saviour.

“Cardinal Pell has always helped victims, listened to them and considered himself their ally,” his office said early last year. Pell had “led from the front to put an end to cover-ups, to protect vulnerable people and to try and bring justice to victims”.

Survivors of sex abuse have nominated Pell as an obstacle to progress. They have queried his priorities.

In the court of public opinion, Chrissie Foster and her late husband Anthony, whose daughters were abused by the same priest, skewered him with their quiet dignity.

Other victims, especially from Ballarat, invariably pause on hearing Pell’s name, before scowling. Perhaps a single image is more damning than any tale — it shows Pell accompanying Ridsdale to court in 1993. Pell later called this decision a “mistake”.

Pell is clerical of tone. Survivors say he reduces lifelong emotional scars to legal abstractions, and oozes loftiness when they seek warmth. In Rome, when the royal commission roadshow came to him, complete with travelling survivors, a new word was coined — “apellogy”.

Pell on Thursday said that he wanted to “clear his name” as soon as possible. Until due process is completed, he might fall back on the “Catholic convictions” he said sustained him during the “dark weeks” of abuse allegations in 2002.

Or seek guidance in the forbidding stare of Daniel Mannix.