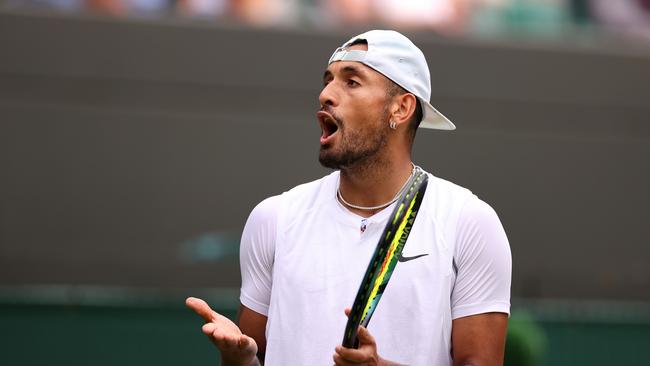

Can you barrack for Kyrgios, he of the backward cap and gratuitous refusal to bow to rules?

The outbursts and explosions of petulance force fans to choose – you’re either with Nick Kyrgios or against him.

Patrick Carlyon

Don't miss out on the headlines from Patrick Carlyon. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The mumbling. That’s what you notice first.

Nick Kyrgios runs a one-sided conversation throughout his Wimbledon quarter-final match. He sounds like a homeless man at the end of a bender.

The chatter starts when he loses the first nine points of the match. To whom he is speaking – his family, the fans, or his imaginary friend Milo – remains unclear.

There’s a brooding chaos to Kyrgios’ demeanour. He seems troubled from within, as if he is not in charge in this straight sets victory, but instead captive to forces unseen.

Confected trouble beckons. It always does. If the enemy does not menace from the other side of the court, he will conjure one.

Can you barrack for Kyrgios, he of the backward baseball cap and a gratuitous refusal to bow to rules?

Do you want this volcanic mix of vulnerability and snarl to win or to lose?

After all, he seeks the tension of his poor behaviour, feeds off it, and for that he will never apologise. Kyrgios forces fans to choose. You’re with him or against him.

He is the first Australian man to reach a Wimbledon semi-final since 2005. Back then, it was Lleyton Hewitt, who also attracted critics for his petulance.

Kyrgios is harder to like, especially since Hewitt (the patriot warrior) has grown up to be an insightful voice for the game.

Kyrgios is also harder to defend. Who warms to a bully who plays the victim?

Yet here’s the thing. It is the lure of Kyrgios’ unresolved defiance which keeps you up until two in the morning. You’re waiting for something to happen, and it has little to do with the score.

His quarter-final outbursts, delivered as promised, are rather subdued. Kyrgios holds his opponent Cristian Garin to account for a supposedly late challenge. “He returns better than he serves,” Kyrgios announces at another point, to no one in particular.

Oddly, the unhinged theatre of Kyrgios’ performance does not flow into his game. He has trick shots, certainly, in a beguiling blend of casualness and calculation.

But against Garin he doesn’t much lunge for the ball or rush to the net. There is none of the scrambling urgency of his next opponent, Rafael Nadal.

He never seems puffed, except in his chats with himself. He whacks the ball from the baseline, in looping drives, in a style which he cannot claim as his alone.

Yet few Australians judge Kyrgios by his game or its brand of power. It’s not really about victory or defeat. He doesn’t invite nationalistic chest thumping as the Hewitts or the Pat Rafters once did.

They instead watch for the Kyrgios moments, those explosions of petulance, which make him more compelling than almost any other higher ranked player.

His antics define him. He yells and cusses. You wonder if he will bark or meow as part of the show.

He demands expressions of adoration from his entourage in the stands.

He spits in the direction of a fan he has labelled the enemy.

He called a linesperson a “snitch”.

He embodies entitlement as it is applied to the worst excesses of his generation. He thinks he is different, even though the rankings, and his lack of grand slam success, say that until now he is just another player who almost made it.

We like to like our sporting stars. When Hewitt whinged, say, or cricketer Dave Warner tweeted, or a footballer unfairly knocks an opponent into next week, we hope regret is expressed so that the poor choices will dim.

Kyrgios isn’t like that, and untested allegations that he assaulted his ex-girlfriend only further confounds those observers who want to make sense of him, or at least put him in a category.

Pat Cash describes Kyrgios’ on-court behaviour as “gamesmanship, cheating, manipulation (and) abuse”. Mark Philippoussis, meanwhile, says Kyrgios is bad for children.

Kyrgios wins plaudits for his candour about depression and mental health.

Yet he is also a man-child perceived to need a smack. He has paid more in fines than most 27-year-olds have earned in income.

He is the iconoclast who finds authorities to disrespect, and the talent who both seeks, and stands to fall to, trouble.

When (record?) numbers of Australians stay up to watch Wimbledon on Friday night, some of them will be barracking for the Australian.

Some of them, understandably, will be cheering for the other bloke.

What unites them is the knowledge that all the accepted versions of the tennis script will be tossed out by a strange gentleman with verbal diarrhoea.