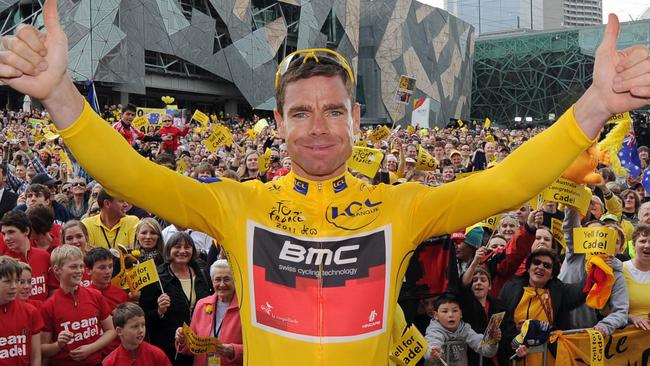

A decade after his Tour de France win cyclist Cadel Evans is loving family life

A decade after becoming the first Aussie to win the Tour de France, cycling great Cadel Evans is embracing a “more balanced life” in a lower gear.

Patrick Carlyon

Don't miss out on the headlines from Patrick Carlyon. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Cadel Evans has just changed another nappy. His eight-month-old son Blake is playing on the floor, while Aidan, two, will soon wake in his upstairs bedroom.

Pandemics and lockdowns have been kind to Evans. They coincided with a conscious choice to slow life, to find time to tinker with one of his special cars, or trim a hedge, or pick vegetables from the garden for dinner.

Evans has belatedly pursued the everyday pleasures that were denied him as a professional cyclist. He has embraced the pressures (and pleasures) of parenthood.

Nestled in the postcard hamlet of Stabio, Switzerland, Evans pounds the streets with a baby jogger, hoping that Blake will drop off to sleep. Sometimes, he can be seen, helmet in hand, as Aidan tries to escape on his balance bike.

Evans wakes at 1am to check the children. He looks after them during daylight hours so that wife Stefania gets rest from the eternal grind.

They have no babysitter, no family to take over for a few hours. They avoid screens. Evans calls their lot “old-fashioned”.

Speaking on the phone to a backdrop of shrieks and gurgles, Evans speaks of the simplicity of forest walks and (relatively) leisurely bike rides.

He extols a private fulfilment that compares favourably with the public adulation of being the first Australian to win the world’s biggest bike race, the Tour de France, 10 years ago next month.

An interloper from the wrong side of the world, Evans overcame the cultural barriers of European sporting prestige, as well as plenty of bad luck. He was the oldest winner, at 34, since World War II. Evans did it clean, too, in an era when most winners were later found to be doping.

He now evokes a contentedness that the stony intensity of professional bike racing would not allow. Evans, the cyclist, projected a self-made loner quality. Preoccupied and distracted, Evans was a media manager’s nightmare. He once threw a journalist his cracked helmet after a race accident and said: “There’s your interview.”

Evans, the father, is more mellow. He no longer talks about this as he inwardly thinks about that. Right now, sleep is the only thing (in the universal lament of parents) that Evans wishes he had more of.

“If you’ve been there you understand, but until you’ve been there people don’t really seem to understand,” he says.

Evans has helped raise Robel, who was abandoned in the streets of Ethiopia as a 15-month-old, since 2012. He and his first wife, Chiara Passerini adopted the boy a couple of years before they split up.

Robel and Evans would catch trout and go sailing. Robel taught Evans to glimpse life outside the professional bubble, to grasp that the once trivial things mattered, and that the once seemingly vital things, like split seconds and heart rates, did not.

Evans met Stefania, an Italian ski instructor, after his marriage broke down. The couple share a passion for fitness; as Evans speaks on the phone, his wife is completing a regular workout in the home gym.

“I don’t know any other job that takes time like being a dad or mum,” he says. “Even air traffic controllers get a break. Raising children doesn’t give you a break. The not having any respite is my observation of the hardest part of being a dad. Seven days a week, 24 hours a day.”

He delights in the small things, like baby steps. Blake’s ability to play on the floor, for up to an hour, offers a temporary freedom not possible two months ago.

“When I first became a dad, suddenly everything I did meant more to me because it was also for someone else. Obviously my priorities have changed. I’m not doing tens-of-thousands of kilometres a year on the bike. It’s all about the kids.”

Evans remembers crossing the finish line on the Champs Elysees in 2011, then hugging mates. He had photos with a requisite toy kangaroo perched behind the handlebars, then headed to a hotel for a party of pizza and beers.

Soon enough, perhaps the next morning, he turned his thinking to the next race, in Colorado. A requested trip of appreciation to Australia seemed, to his professional mindset, unworkable. It conflicted with his racing schedule.

He spoke to his mum.

“Will anyone come?” he asked her.

“You’ve got no idea,” she replied.

“I came out of the airport and there was like a three-storey high billboard with a picture of me on it, saying congratulations,” he says. “I thought, ‘oh, hang on a second’. That was when I started to realise how many Australians had been along, not just the ride being the Tour de France, but my whole journey.”

Evans built his career on suffering. If he hurt more, and tried harder, he believed he might just succeed. The motivation came from within.

Evans moved as a child, from an indigenous community in the Northern Territory, to northern NSW, then Arthurs Creek, north of Melbourne, where school was a 10km bike ride away.

Being kicked in the head by a horse was perpetuated as a foundation story. His mother Helen was told Evans might die or be paralysed as he lay in a coma. The headaches that plagued his cycling career, likely from the childhood accident, goes to the bigger tale of grim determination.

There’s more now. Life is bigger than the next race. Evans doesn’t miss the unrealistic expectations of others, the weight of unfair judgment. Or the intensity of the daily demand to get on the bike, through rain, ice and snow, and push his body as far as it would stretch.

For decades, he missed countless weddings and social events. He would come home for a day after competing, go for a ride, maybe see a few friends. “You take your clothes out of the suitcase, put your clothes back in your suitcase then go to the airport to go somewhere else,” he says. “That’s the life of a cyclist.”

But he does miss the ruminating that the solitude of full-time training afforded.

“That mental space, there’s a lot of time to think and reflect on life which I became very used to and a little bit dependent on, to be honest,” he says.

“I still ride and exercise. It’s not just the physical side but also that mental space to unwind. The whole idea of riding is now exactly the same thing as when I was four or five years old, the freedom and the liberty.”

Hunger unites those who achieve at the highest levels. In cycling, it applied to all those lonely days away from races, where unobserved discipline is critical. Once “the hunger goes, and you see it in riders, that’s when it is time to stop”.

Evans, an SBS TV commentator for the upcoming Tour de France, marvels at the increasing depth of competition at the elite level. He will have to research the back stories of up and coming riders: while passionate about the biggest races, his cycling gaze now extends to the “look in the eye of a young child riding a bike down the street”.

He firmly believes that the sport is cleaner than it once was. Catching out cheats – only four from 16 Tour de France winners between 1998 and 2013 remain untainted by drug scandal – is poor publicity in the short-term, but the only answer for long-term success.

Evans is chuffed that the 10th anniversary of his win is a big deal. He tended to think that people forgot sportspeople once they stopped competing, despite the fact a major Victorian cycling event - the Cadel Evans Great Ocean Road Race has been named in his honour.

On the anniversary, he will gather with those who celebrated with him on the day. Beers will flow as he seeks to rekindle the special unity of that moment. In Tuscany, after friends fly in from Europe and America, he plans a wine tour by bike.

The ordinariness of the plans go to his gentler approach.

He has re-released his book, The Art of Cycling, which includes an updated preface paying homage to the song which he thinks best describes his career, Holy Grail, by the Hunters and Collectors.

But no longer must he be better than he was yesterday; instead, he reflects on “problem solving, disconnecting, insulating myself from unwanted distractions, and being open to natural surrounds”.

“Ten years ago my life was so intense and my focus was on the one thing, my performance on the bike,” he tells Weekend. “I certainly say I was really happy 10 years ago. Now I’d say I’m really happy - and balanced.”

Supplied photos via memories.com.au