James Campbell: Palace letters won’t reignite push for a republic

For anyone hoping the big Palace letters reveal would turbocharge a fresh push for an Australian republic, the correspondence between Sir John Kerr and the Queen’s private secretary proved to be a big disappointment, writes James Campbell.

James Campbell

Don't miss out on the headlines from James Campbell. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is a sign of how much the dismissal has receded into history that when the Labor Senator Jenny McAllister decided this week to post something on Facebook in the wake of the release by the National Archives of the so-called Palace letters, she felt the need to caption photographs of Gough Whitlam and Sir John Kerr, explaining that one had been the prime minister and the other governor-general.

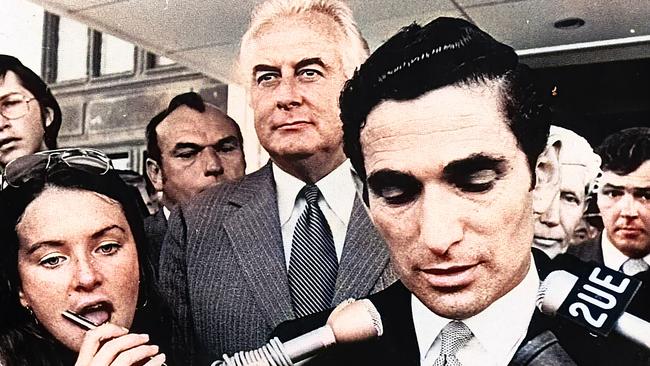

Not very long ago, the photo she used to illustrate her post — of Whitlam addressing the crowd from the front steps of the Old Parliament House on the afternoon of his removal from office — would have been instantly recognisable to every Australian.

Clearly, almost 45 years on, the Senator, who was two at the time, couldn’t be sure this was the case. Which is fair enough, I suppose. Everyone involved is either dead or in their dotage.

The Australian Labor Party, and Australian Left more generally, love an historical villain and for them Kerr fits the bill, but clearly the passions the dismissal once aroused have ebbed if there is a need to draw an arrow explaining who he is.

Sadly for anyone hoping Tuesday’s big reveal would rekindle the passions of 1975, turbocharging a fresh push for an Australian republic, it took about 40 minutes for news to filter out — via Twitter — that the correspondence between Kerr and the Queen’s private secretary Sir Martin Charteris in the lead-up to and wake of November 11, 1975, was going to be a big disappointment.

The critical document was Charteris’s letter of November 4 in which he expressed the opinion the reserve powers — which Kerr was to use to sack Whitlam a week

later — undoubtedly did exist but “to use them is a heavy responsibility”.

On Charteris’s side, the correspondence could be summed up as “Goodness, you have a difficult job and we don’t envy you but we’re sure you’ll do the right thing.” In other words, they were humouring him, saying as little as possible, hoping the situation would resolve itself.

It would seem the only person who expected the correspondence would show anything else was Jenny Hocking, the historian who went all the way to the High Court to obtain its release.

On Tuesday she wrote in The Conversation — in a sentence that would have been more at home in the Daily Mail — that the “impact of this extraordinary decision is being keenly felt in Buckingham Palace and with some trepidation, since the letters will be released against the wishes of the Queen”.

Exactly how much trepidation is debatable.

Speaking from his home in Perth, the Queen’s former private secretary Sir William Heseltine said he was happy the letters had finally been released as he knew they would dispel “disinformation that was going about”.

More interestingly, Heseltine made it clear the view in the Queen’s private office in 1975 was that Kerr had acted before he needed to.

“All of us in the office in London thought that if Kerr had been able to hold his nerve for just a day or two more, there probably would have been a political solution to the problem, which would have avoided a lot of fuss,” he told The Australian.

“I think various possibilities would have eventuated. Somebody in the Senate would have given way … and the vote (on supply) could have been passed in the Senate. That’s one thing I think might have happened.”

That may or may not be so and Kerr was not to know how likely one of the Coalition senators was to crack.

But it raises the fascinating possibility that if Kerr had actually sought the advice of the Queen, rather than keeping up a commentary on his situation, there might not have been a dismissal.

Moreover, if Charteris, Heseltine, and by extension the Queen, had been prepared to tell Kerr their thinking off their own initiative — in other words, to really properly interfere in how he did his job — Whitlam might have been denied the political martyrdom that has done so much to obscure the incompetence of his government.

On Tuesday morning, as reality dawned on the readers that there was no smoking gun of royal involvement, it was tempting not to feel a little sorry for Hocking: the Palace letters had promised so much and delivered so little for all the time and expense involved in getting the chance to read them.

To her, they have “proved to be every bit the bombshell they promised to be, and neither the Queen nor Sir John Kerr emerge unscathed” … “the damage done to the Queen, to Kerr, and the monarchy is incalculable”.

This claim was undermined more than somewhat by her assertion in the same piece that as “we delve deeper into them, just as important as what is in the letters will be what isn’t there — the gaps, the events and people who should be but aren’t”.

James Campbell is a Herald Sun columnist