It’s 25 years since the Port Arthur massacre, and we owe it to the victims to keep gun laws tight

Politicians must show the same courage they did after the Port Arthur massacre, and defend Australia’s world-leading gun control laws.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

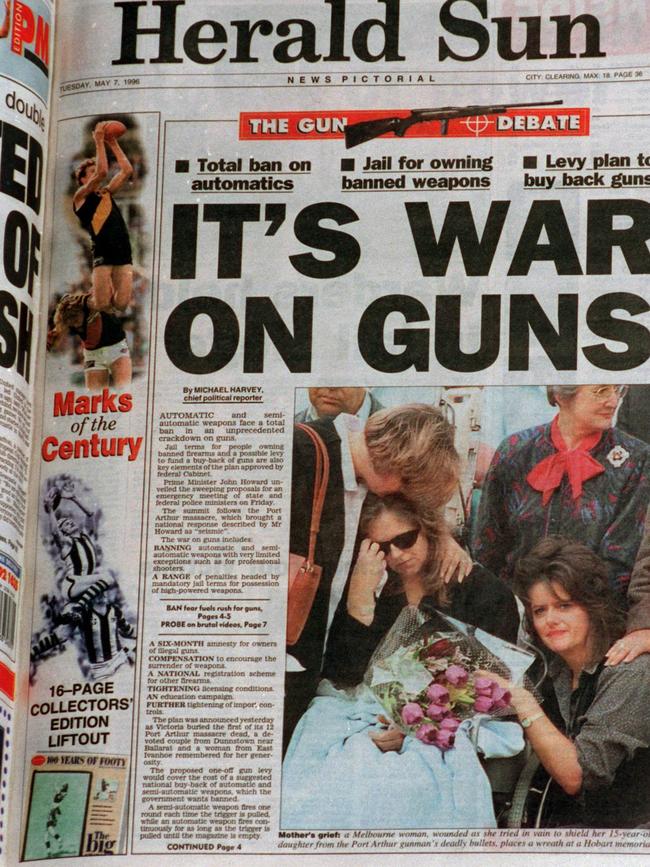

Opinion: In 1996, politicians from across Australia showed real leadership, and committed to the National Firearms Agreement, a 10-point plan to strip semiautomatic and self-loading firearms out of the community.

Tragically, the leadership came too late to save the 35 people killed by a lone gunman armed with a military rifle who shot them at close range at the Port Arthur penal colony in Tasmania on Sunday, April 28 that year.

Nonetheless, state and territory leaders displayed courage by doing the right thing, even though they knew it would infuriate the powerful shooters lobby, and alienate ordinary citizens who had never done anything wrong, and were upset at losing their legitimately-held weapons.

The greatest political courage of all was shown by then-prime minister, Liberal John Howard and his then-deputy, Nationals Tim Fischer, who drove the states to adopt the firearms agreement despite it disproportionately affecting conservative Coalition voters.

A quarter of a century later, the agreement, signed with such hope and good faith in those dark days after Port Arthur, has done its job in stopping mass shootings. It has taken large-calibre, rapid-fire guns out of the community.

But the agreement has never been fully implemented. Either in legislation, or in the way the laws are interpreted, rules vary between states. The legislation remains under constant attack from the shooters lobby.

It seems some are treating Port Arthur as a distant event which we’ve moved on from, and the decisions taken then by politicians acting in the national interest should be disregarded.

This is wrong.

As a young journalist working in Tasmania on that autumn Sunday in 1996, I was one of the first reporters at the scene. It remains a very real, traumatic event for the people of Tasmania, and for the families of the 35 people killed, and 20 more who were shot but survived. Economically, the Tasman Peninsula took years to get back on its feet. Emotionally, it’s still recovering.

Every adult in Tasmania remembers where they were when they heard about Port Arthur. I was working in Northern Tasmania covering a fatal car crash when I got a call from a senior police officer, shortly after 1.30pm on that day. With a photographer, we got to Port Arthur as fast as a light plane and hire car would take us.

I remember the convoy of ambulances, winding its way slowly along the road out of the tourist site as we drove towards the scene. No cars coming the other way, just a line of ambulances, carrying the dead and injured to Hobart.

I remember the profound shock the survivors were suffering as they drove out through the roadblocks in the early hours of the next morning. Some slugged wine, struggling to hold the bottles with shaking hands. A pregnant woman vomiting. Tears, and disbelief.

The years of pain afterwards, as the community struggled to decide how to respond to the massacre, whether the Broad Arrow Café should be torn down or kept as a memorial, and how best to allow emotional wounds to heal. I remember how you could see the reflection of Port Arthur gunman Martin Bryant’s house in the glass doors of the gun shop down the road in New Town where he bought his deadly weapons.

Unlike the US, Australians have no right enshrined in our constitution to own a gun. Almost no-one in this country has the need to own and operate a rapid-fire weapon, designed as a killing machine.

And there is no doubt Australia’s gun culture, or at least the public face of it, has changed in 25 years.

I grew up in regional Tasmania. People had guns. Every farmer had at least one rifle laying around somewhere. Some of my friends enjoyed shooting as a hobby, spending the weekend with mates in the bush, having a few beers and hoping to bag a deer to be butchered for meat. Kangaroos and rabbits were fair game. As kids, we occasionally mucked around with air rifles and spud guns, shooting cans off tree stumps.

When my country high school decided our drama class would perform the World War II-era play Tokyo Rose at the local memorial hall back in the ‘80s, some kids brought in real rifles to be used in our marching scenes.

This would be unthinkable now.

But the gun laws remain under attack. One of the most blatant and disgraceful efforts to undermine them was proposed, of all places, in Tasmania prior to the 2018 election.

Then-police minister Rene Hidding wrote to a firearms consultation group weeks before the election – a letter not revealed publicly until the day before the polls – promising to soften the laws by, among other things, extending gun licenses from five years to 10 years, allowing some farmers to use silencers, and getting rid of the provision which saw firearms automatically removed from people who failed to properly secure them.

Hidding, who said he was seeking to assist farmers with pest control – also promised to ask the national police ministers to allow more sporting shooters access to pump-action and rapid-fire guns.

The then-Liberal premier Will Hodgman crab-walked away from the offer, and the changes were thankfully never implemented.

On March 15, 2019, I was a long way away from Tasmania, in the Turkish city of Gaziantep, near the Syrian border, to cover the latest court appearance of terrorist Neil Prakash, when I woke to the awful news that a lone gunman had murdered 51 worshippers at two mosques in Christchurch.

I ran downstairs and joined a group of people watching the live-stream filmed by the gunman of the attack, which Turkish TV broadcast as people ate their breakfast. It soon became obvious that an Australian was responsible, and that he had amassed an arsenal.

The gunman would never have been able to obtain those guns in Australia under our laws, but tragically was able to do so, legally, in New Zealand. But he was one of ours, born and raised here. Without our laws, it could have happened here.

Every politician in Australia coming under pressure from the shooters’ lobby to water down our world-leading firearms laws needs only to look at our close neighbours and friends across the ditch to see the tragic result of loose gun laws. Or they can look in their hearts and find some of the courage showed by their political predecessors 25 years ago, and work to make our laws better.