Radical surgeon exhibited dead man’s bladder stone in Collins St

James Beaney prescribed booze to patients, operated wearing diamond rings, served champagne in surgery and infuriated other doctors.

In Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from In Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

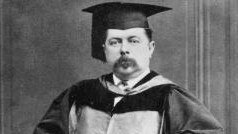

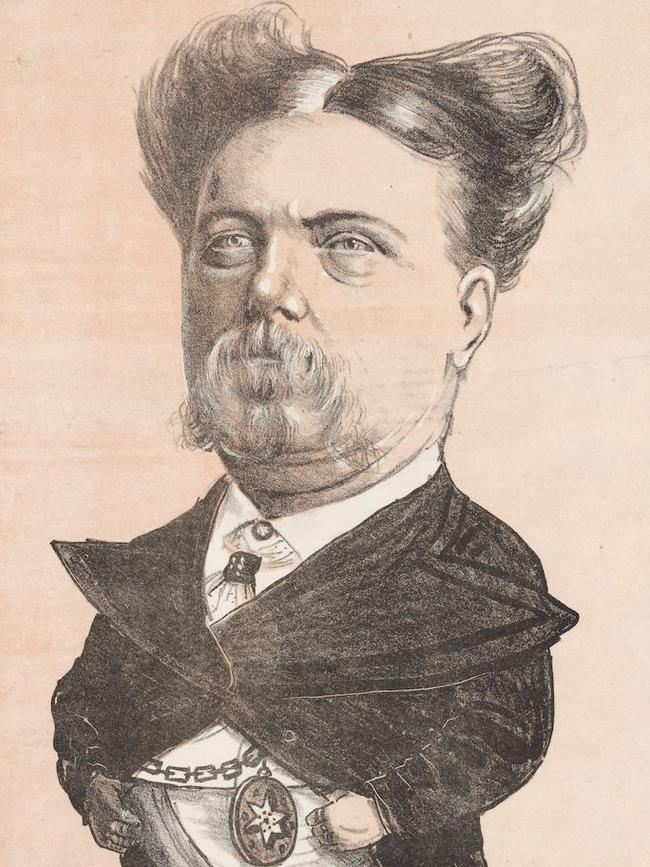

James Beaney – aka Diamond Jim – was one of the most notorious and colourful surgeons in 19th-century Melbourne.

A shameless self-promoter, he earned a fortune thanks to his reputation as a risk-taker who would operate when no other surgeon would dare.

But the risks didn’t always pay off, and eventually Beaney found himself facing trials for the murder of a 21-year-old barmaid and the death of a patient whose bladder stone he removed.

Diamond Jim is the subject of a new episode of the In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters:

Ben Oliver, the founder of Drinking History Tours in Melbourne, says the English-born surgeon earned the nickname Diamond Jim because of his ostentatious frock coats and jewellery.

“He had these amazing coats that were embellished with velvet collars and most famously he had diamond rings on most of his fingers,” Oliver says.

“He had a bejewelled gold fob watch with a chain that had a diamond pendant, so just completely blinged out in jewellery.

“And that was when he was both entertaining friends at his opulent home on Collins Street or in fact if he was in surgery.

“He was famous for wearing his diamond rings while he was actually performing surgery.”

Beaney’s other nickname was Champagne Jimmy, and he was renowned for his love of alcohol and his lavish entertainment of both friends and surgical students.

“People could go and watch him perform surgery. Typically, this was students who would want to see the master at work,” Oliver says.

“He would often serve champagne during and after his surgery.

“It didn’t really matter whether the patient survived or not – champagne was being served regardless.”

Oliver says Diamond Jim regularly consumed a bottle of claret for breakfast, a small bottle for champagne for lunch, and more champagne at dinner.

He was also fond of prescribing alcohol as a treatment for his patients.

Oliver says the records show that in one month in 1883, Beaney saw 63 patients and prescribed 122 ounces of brandy, 101 bottles of ale or porter, and two bottles of champagne.

In 1866, Beaney faced trial for the murder of Mary Lewis, a barmaid and mother of two who it appears may have consulted him for an illegal abortion.

On his third visit to her lodgings, he administered chloroform to help her sleep, but she died the next day.

The jury narrowly failed to reach a verdict and Beaney was lucky to survive, allowing him to continue his scandal-plagued medical career.

“He really was only one vote away from the jury convicting him of murdering a patient and him going to the gallows,” Oliver says.

“So he really skirted the edges of ethical surgical conduct even for that time.”

Beaney, who performed surgery in an old bloodstained coat, was also “the king of self-promotion”.

“He would advertise successful surgeries. He would advertise unsuccessful surgeries,” Oliver says. “He would simply omit the fact the patient died during surgery.”

In 1875, when Beaney performed surgery to remove a bladder stone from patient Robert Berth, it was discovered during the operation the mass was much bigger than expected.

“Beaney hadn’t made an incision big enough to actually remove the stone, so the only way they could get the stone out was basically forcing it out of this incision,” Oliver says.

“It ended up causing the surgical instruments to buckle and bend, and then of course that led to more rupturing, and then there was an inflammation of the bladder that followed from that.

“All of this took place while Robert was not under any anaesthetic.”

Unsurprisingly, the patient died during surgery.

But that didn’t stop Beaney promoting himself as the surgeon who had removed the 180g bladder stone.

“You would think that most doctors wouldn’t take this as an opportunity for self-promotion,” Oliver says.

“Of course, Dr Beaney is not like most doctors of the 19th century.

“He decided that because this was such a remarkable bladder stone he would promote the fact that he performed surgery on this patient – and simply omit the fact that he died while it was being removed.”

So Beaney arranged for the huge bladder stone to be put on public display in the front window of a bookseller’s shop in Collins St.

Next to the specimen was a printed card that read: “This stone was removed from a patient’s bladder at the Melbourne Hospital by Dr James G Beaney.”

“No mention of the death of the patient,” Oliver says.

“This just inflamed an already poor relationship that he had with the medical fraternity.”

Concerns were raised about Beaney’s conduct, a police investigation was opened, and the patient’s body was exhumed to conduct a post-mortem examination.

Beaney faced charges of culpable negligence, but after the wealthy doctor hired a clever lawyer, he was acquitted and again walked free.

Beaney later became a state MP, and died in Melbourne in 1891, aged 63.

Listen to the interview about James “Diamond Jim” Beaney with Ben Oliver in the In Black and White podcast on iTunes, Spotify or web.

See In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper Monday to Friday for more stories and photos from Victoria’s past.