How Squizzy Taylor and a cast of misfits ran riot in Fitzroy’s wildest street

Its name is barely known today, but a century ago Fleet St was a magnet for Melbourne’s most notorious criminals and the frequent scene of shootings, beatings and wild assaults, so how did it meet its demise? LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

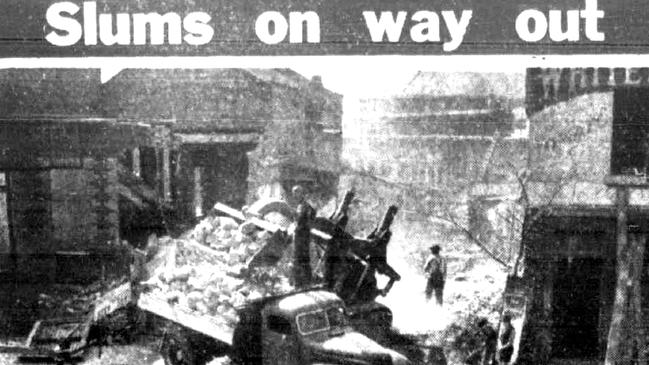

Fitzroy’s Fleet Street had a reputation for being wild and lawless from the 1870s to 1930s, but it was during the 1950s, as a result of the deplorable condition of its housing, that it went through its greatest shake-up.

Unless you’ve spent time exploring the backstreets of southern Fitzroy, you’d be forgiven for not even knowing that Fleet Street exists.

It’s hidden away behind the Convent of Mercy, which sits on Nicholson Street, opposite Melbourne Museum.

It bisects the site of Fitzroy’s first major Housing Commission project, built in the 1950s. Unlike the towers of the nearby 1970s Atherton Gardens Estate, the flats in Fleet Street are low-rise.

At their centre is a quiet park setting which belies the old street’s turbulent past.

In late 1918, the second-in-charge of Victoria Police, Superintendent Davidson, was quoted in the newspapers as saying Fitzroy was “the home of Melbourne criminals”.

The assessment wasn’t particularly well received by the Fitzroy Council, and a public war of words ensued.

The Chief Commissioner of Police subsequently requested that reports be made by Fitzroy’s longest serving police officers to prove that there was substance to the superintendent’s claim.

One of those who filed a report was plainclothes Constable Bartolo Mafferzoni.

He agreed that Fitzroy was the home of Melbourne criminals and outlined the reasons for it being that way.

He blamed the short distance from the city of Melbourne, the large number of boarding houses, and the substandard condition of the buildings that people were forced to live in.

His report also listed the worst streets of the suburb, and Fleet Street was included.

“These houses are not fit for any person to live in,” he wrote, “very few of them have a bath in them, they are not ventilated enough.

“The better class of people will not live in these wretched houses, yet the unfortunate class are glad to get them at any cost.”

Just eight months after Mafferzoni’s report, the rear of a sly grog shop at 31 Fleet Street was sprayed with bullets by a group of gunmen.

Though the shooting seemed to be more about intimidation than assassination, three people were admitted to hospital with bullet wounds.

The most seriously injured was Minnie Dean. She was perhaps the toughest person in Melbourne.

She stopped a bullet with her forehead.

The missile flattened against her skull and sent a fine fragment of bone into her brain.

After the fragment was surgically removed, she went on a short holiday to the country before returning to Fitzroy to resume her usual occupation of brothel-keeper and sly grog proprietor.

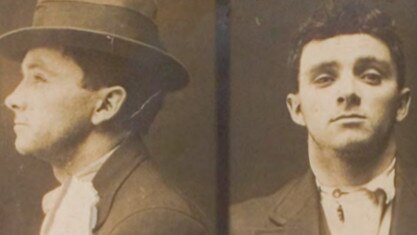

Squizzy Taylor, already a gangster of some notoriety, had been seen in the vicinity by police at the time of the shooting, and though the actual crime could not be pinned on him, he was convicted of loitering with intent.

The conviction was later quashed under appeal.

Fleet Street hadn’t suddenly become lawless in 1919.

It had been that way for some time.

The story of the Leyden family of 10 Fleet Street could alone fill a book.

During the 1870s to 1880s the Leydens kept newspaper scribes busy with tales of violence, brothel-keeping, and larrikin gangs.

There were other houses in the street that contributed to Fleet Street’s reputation too.

In 1882, Mary Flintoff, a brothel keeper at 23 Fleet Street, smashed the nose of a cab driver.

In 1888, Margaret Caulcutt, of 14 Fleet Street, was convicted of baby farming.

One child had died in her house and another was found by police to be severely malnourished.

During 1904, Joe Basford hired out one of his widowed mother’s rooms at 31 Fleet Street to street prostitutes, actively recruiting their custom from busy Victoria Parade.

Living at the Basfords at the time was American gunman “Long” Cyril Loader.

Known as “the gentleman burglar”, Loader was sentenced to two years for breaking into seven Melbourne dentists in 1904 to steal the gold used for fillings.

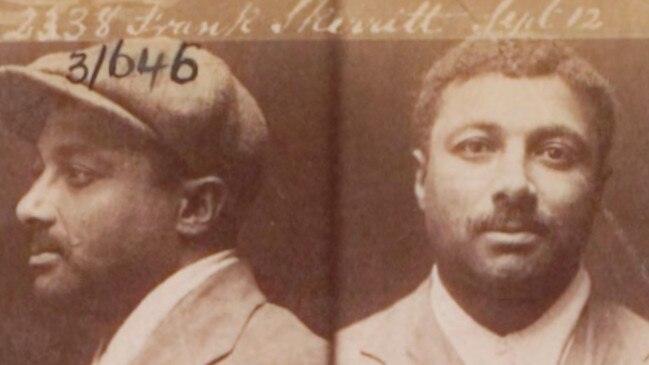

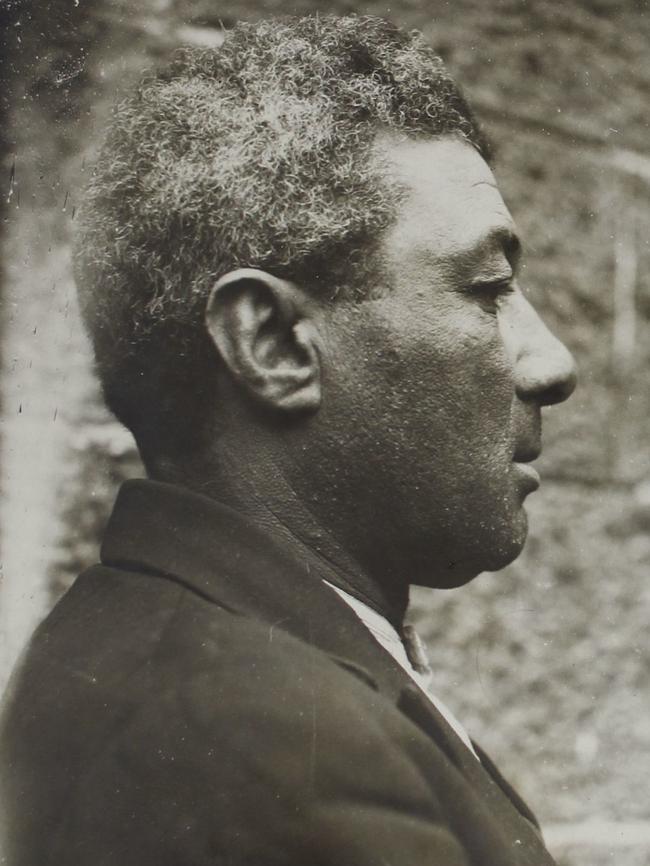

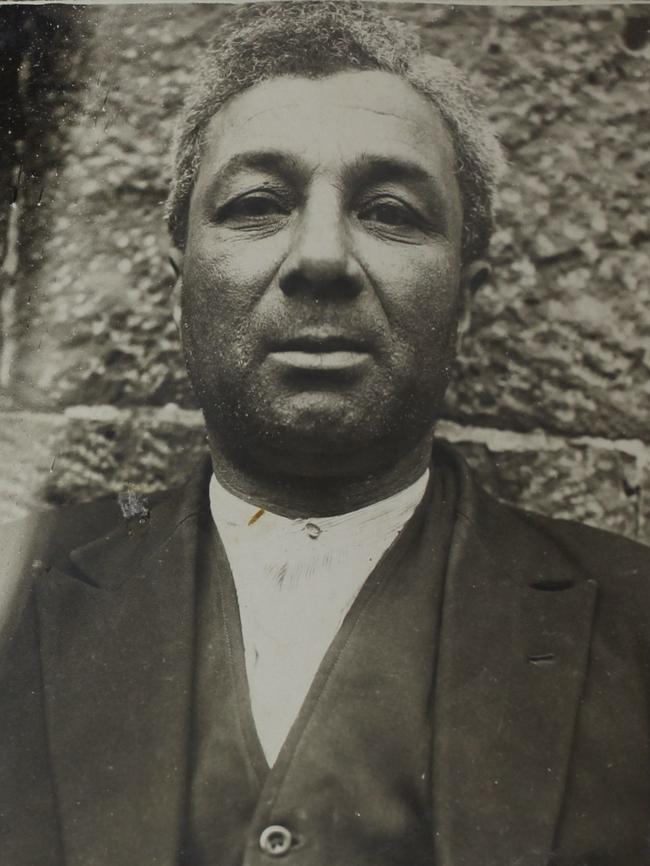

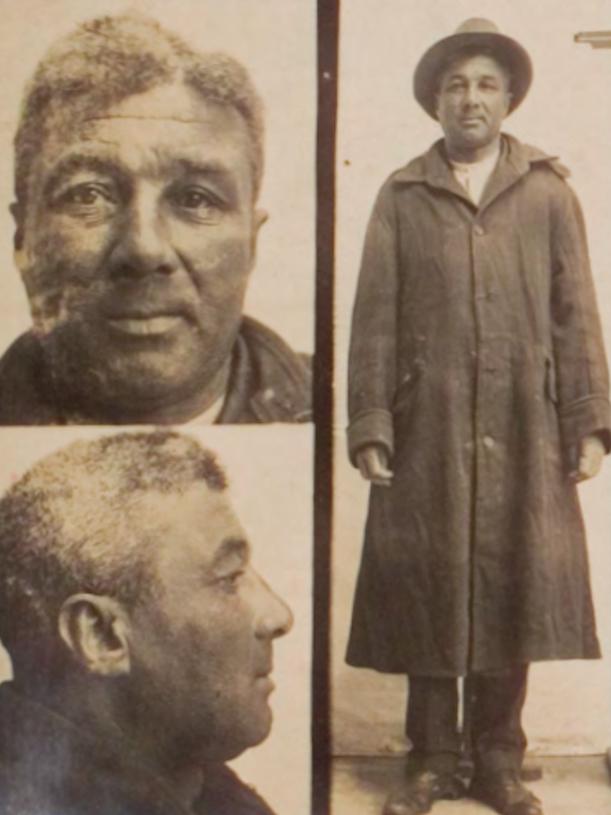

In 1917, Arthur Skerritt, of 23 Fleet Street, got in a drunken scrap with police outside his house.

He was a WWI vet and told the arresting officers they hadn’t the courage to fight at the front like he had done.

Two years later Skerritt fired shots through the front door of 27 Fleet Street, a brothel owned by Charlie Foo and managed by sisters Minnie and Myrtle Anderson.

None of the bullets found their mark.

The explanation later given for the shooting was that one of Skerritt’s fellow gang members was upset with Myrtle after contracting a disease.

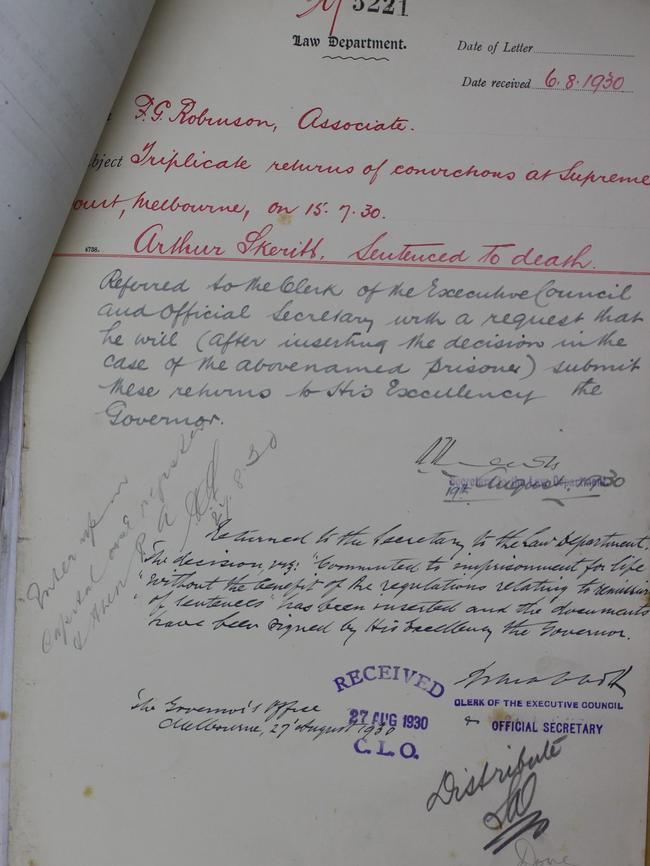

In 1930, Skerritt murdered an elderly Fitzroy Street shopkeeper.

The motive was robbery.

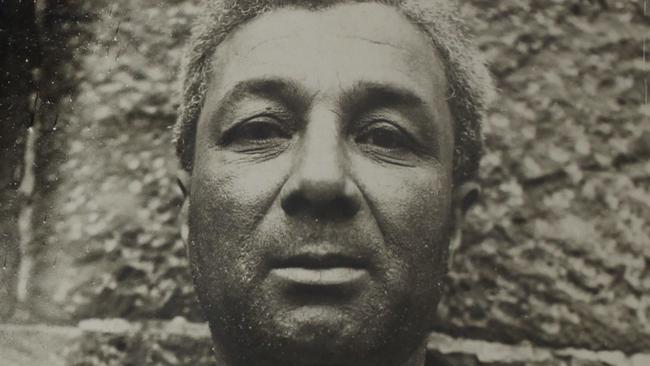

He was convicted and given a death sentence, which was later commuted to life in prison. Though he was 45 years of age, specialists analysed Skerritt as having a mental age under 15.

Over the next few decades, Fleet Street and its surrounds became less known for crime and more known for substandard housing.

The buildings had deteriorated even further since Constable Mafferzoni’s 1919 report.

In the early 1950s, after decades of lobbying, most of the block on which Fleet Street stands was compulsorily purchased by the State Housing Commission and the old houses demolished. In their place were built the flats that are still there today.

Michael Shelford is a Melbourne writer, researcher, and creator and guide for Melbourne Historical Crime Tours.

Listen now to an interview with Michael Shelford about Arthur Skerritt and Fleet Street in today’s new free episode of the In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters on Apple/iTunes, Spotify, web or your favourite platform.

Listen to the previous two episodes in the Larrikins & Laneways series on how Collingwood’s baddest crime family ruled the streets and Melbourne’s feared slumlord queen.

See In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper Monday to Friday for more stories and photos from Victoria’s past.