How Melbourne fought 1919 Spanish flu with fresh air, formalin and crazy contraptions

While tens of millions of people died worldwide in the 1919 Spanish flu pandemic, Australia recorded one of the world’s lowest death rates. Here’s how we did it.

Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When Australia fought the Spanish flu in 1919, the public health advice looked a little different from today’s COVID-19 rules.

But some of it must have worked.

Australia fought off the pandemic 101 years ago better than almost any other country, including New Zealand.

Australia’s fight against the Spanish flu is the subject of a special edition of the In Black and White podcast, available today.

The estimated global death toll from Spanish flu varies from 30 to 100 million.

Australia’s toll of up to 15,000 people was high, but less than a quarter of the country’s 62,000 death toll from World War I.

Our death rate of 2.7 per 1000 of population from Spanish flu was one of the lowest recorded of any country.

An article headed “Women to Women” in Melbourne’s respected Argus newspaper from February 12, 1919, gives an intriguing insight into the fight against the pandemic.

Families were urged to keep away from crowds and avoid trams and trains.

But they were also advised to live as much as possible in the open air, and keep the house doors and windows open night and day if possible.

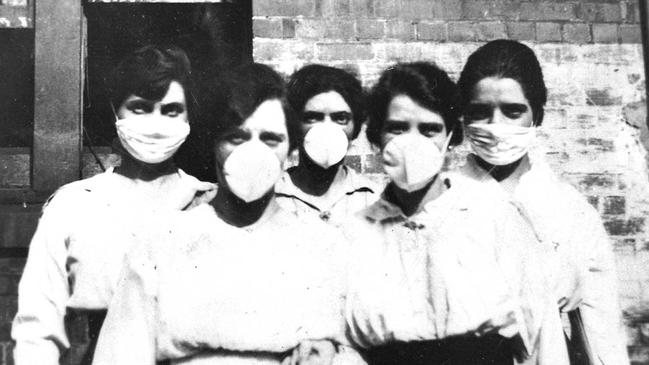

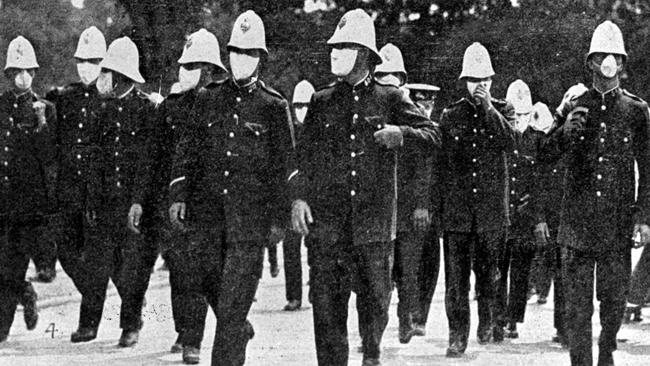

Wearing face masks was common in public to beat the spread, and The Argus advised women to keep a supply of butter muslin and a few made-up masks on hand.

And if a household member fell sick, women were advised to put the patient in a separate room and hang a sheet saturated with a disinfectant solution over the door.

Women were told to keep handy a supply of a disinfectant such as formalin – now known to be highly toxic – to use if a family member fell ill with Spanish flu.

“The person who is likely to have to do the nursing should have a couple of plain cotton dresses in readiness, and a print or muslin cap to cover the hair completely,” The Argus added.

Women were advised to bathe daily, wash hair frequently, keep the house clean, and cover food to deter flies.

“Keep calm and unafraid. Fear lessens the power of resistance. Remember that most of the patients recover,” the article urged.

“Take all precautions, but think as little as possible about the epidemic, and try to keep the home cheerful and the children happy and occupied.”

As Australia fought the Spanish flu, state borders were closed, travel was restricted, quarantine camps were set up, and public events were cancelled.

The tyranny of distance worked in our favour, and Australia was able to learn lessons from overseas and prepare for the arrival of the Spanish flu.

The Exhibition Building in Melbourne was transformed into a hospital for 1500 Spanish flu patients at a time to take the overflow from Melbourne’s overcrowded hospitals.

The newly created Commonwealth Serum Laboratories produced millions of free doses of a new flu vaccine for Australian troops and civilians.

And photographic firm Kodak introduced an “inhalatorium” at its Abbotsford factory to protect employees.

Twice a day for four minutes, staff lined up along either side of the 5m-long structure and pressed their faces into the oval-shaped openings.

Staff breathed in steam containing sulphate of zinc solution, designed to disinfect their throats and air passages.

Elsewhere, inhalation chambers were set up where the public could inhale formalin fumes, despite medical advice this was dangerous.

Other people tried to protect themselves by hanging garlic around their neck, or wearing masks soaked in eucalyptus oil and creosote.

Play the free In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters on iTunes here or Spotify here or on your favourite platform.

Listen to previous episodes including the tale of why the Freddo Frog almost didn’t exist, the Essendon Football Club trainer who was a quack doctor and drug fiend, and the tale of bushranger Dan Kelly’s apparent return from the dead.

And check out In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper Monday to Friday to see more stories from Victoria’s past.