From Aboriginal “protector” to callous skull collector

When George Augustus Robinson was employed as the official protector of Tasmania’s Aboriginal people, he vowed to “do good”. Instead, Robinson committed a macabre act of betrayal.

In Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from In Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When George Augustus Robinson was employed as the official protector of Tasmania’s Aboriginal people, he vowed to “do good” for those in his care.

Instead, Robinson committed a macabre act of betrayal – decapitating their bodies, stripping their flesh, and distributing their skulls to collectors in Europe.

The disturbing tale is told in the latest episode of the free In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters:

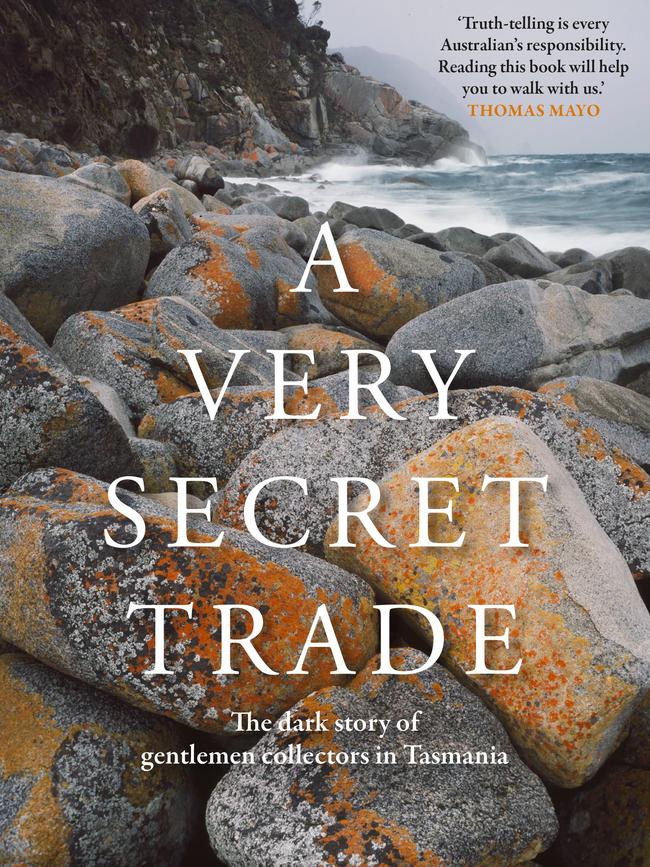

Tasmanian historian Cassandra Pybus shares the story in her latest book, A Very Secret Trade: The Dark Story of Gentlemen Collectors in Tasmania.

Pybus uncovered a thriving 19th century trade where European collectors sought out scores of skulls and skeletons of Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

“It becomes a big issue in England that the Tasmanians are about to become extinct,” Ms Pybus says.

“And so there’s this big scramble to get hold of Aboriginal remains, and so the only way you’re going to get them and be sure they’re Aboriginal is to go into the grave sites.”

Many eminent colonial figures were involved in the secret trade.

Robinson was a poorly educated London tradie when he emigrated to Tasmania in 1824 in search of a better life for his large family.

Robinson’s job was to persuade Aboriginal people to leave the land and place themselves under the governor’s protection.

“He seems to have a genuine deep religious conviction about saving the Indigenous people of Tasmania from destruction that he could see was inevitable and bringing them into the light of God,” Ms Pybus says.

Robinson became the commandant of an Aboriginal settlement on Flinders Island, and later the chief protector of Aboriginal people in the new colony of Port Phillip across Bass Strait.

When new governor John Franklin and his wife Lady Jane visited Flinders Island, they were entertained by Aboriginal dancers before she made a startling request.

“As they were leaving, Lady Jane Franklin asked him if he could get her some Aboriginal skulls,” Ms Pybus says.

“And he notes that in his diary.

“(Later) he talks about this man called Christopher and how he ordered the body decapitated and sent it off to someone else to have the flesh taken off the skull and then buried the rest of the mangled body.”

In Ms Pybus’s mind, Robinson is the most abhorrent of the skull collectors she investigated because he understood at a profound level what a terrible betrayal it was.

“He absolutely knew these people very, very well,” she says.

“He knew they had a complete abhorrence, a horror, of anybody interfering with their bodies after death.

“He knew that, but he did it anyway.”

To learn more, listen to the interview in the free In Black and White podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or web.

See In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper every Friday for more stories and photos from the past.