Early Melbourne Pseudoscience: Phrenology skull reading ahead of its time

Of all the pseudosciences to grip early Melbourne, phrenology was one of the most bizarre – and macabre.

In Black and White

Don't miss out on the headlines from In Black and White. Followed categories will be added to My News.

While phrenology is now held in the same regard as reading palms or tea leaves, the belief that experts could “read” bumps on the skull to detect character traits was once widespread.

Early Melburnians flocked to lectures explaining how a protruding forehead indicated a great intellect, or a bump on the crown was a sign of morality.

The role of phrenologists is explored in the latest episode of the In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters, with historian Margaret Anderson, the director of the Old Treasury Building Museum:

It’s one of the occupations featured in the museum’s exhibition, Lost Jobs: The Changing World of Work.

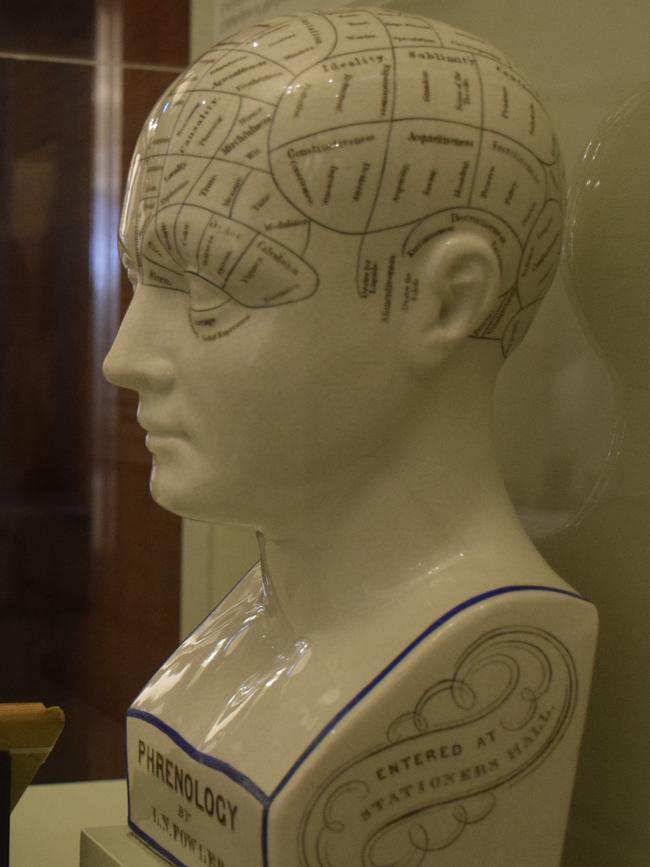

Every region of the skull was believed by self-proclaimed professors of phrenology to correspond with different character traits.

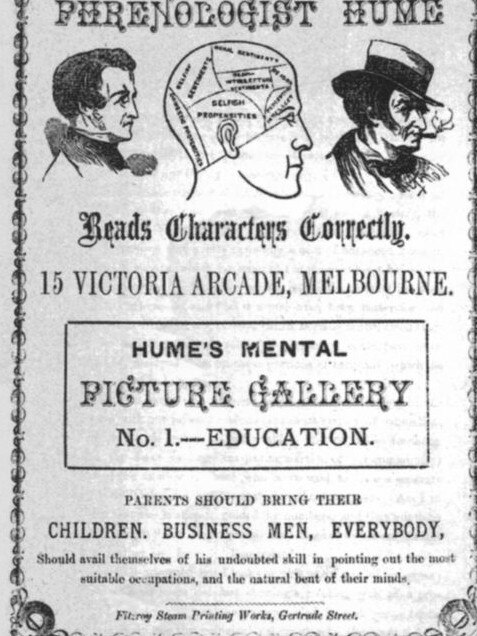

People would pay phrenologists to assess what career they were suited to, or whether a woman would make a good wife.

“My assumption would be that they’d be looking for someone who was amenable, you know, good-tempered, hardworking, all those sorts of things,” Ms Anderson says.

“They divided the skull up into something like 30 faculties and there were busts that were sold which phrenologists could use to map out the skull.”

Ms Anderson says phrenologists had a particularly strong interest in studying the skulls of criminals.

And while their methods have long since been discredited, their beliefs that criminals could be redeemed were well ahead of their time.

“The interesting thing about the phrenologists was that in some ways they were more progressive than the early criminologists who followed them, because the phrenologists actually believed that criminals could be treated,” Ms Anderson says.

“The early criminologists who followed them from the late 19th century … actually believed that criminality came from birth; you were born that way.

“And so there was no prospect then of redeeming, say, a murderer.”

One prominent phrenologist was Madame Sibly, also a mesmerist, who billed herself as the “Wonderful Woman” and dazzled audiences around Australia and New Zealand in the late 1800s.

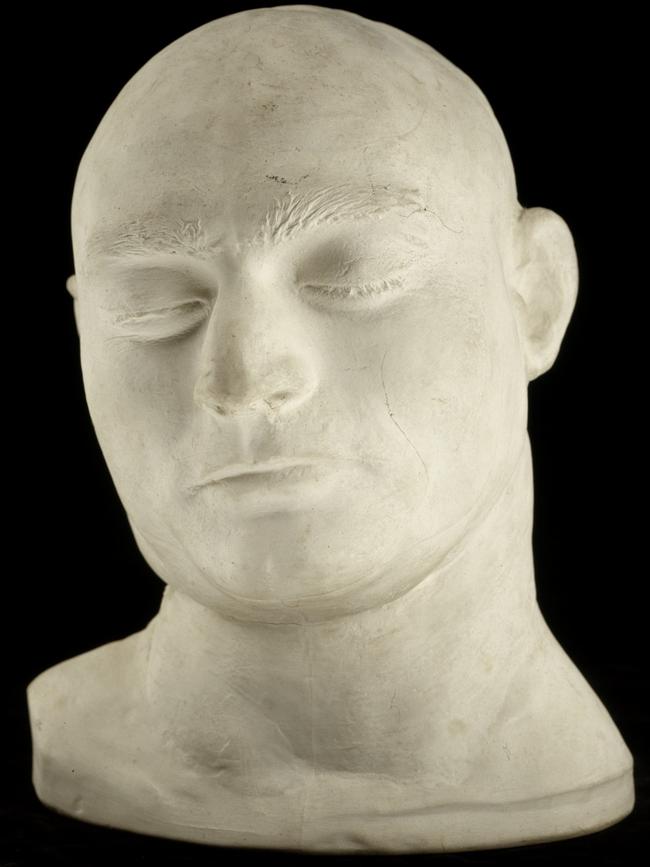

Phrenologists’ interest in studying criminals’ skulls led to the macabre practice of producing death masks immediately after an execution, often while the body was still warm.

“As soon as the body was cut down, the criminal was taken to the morgue and all of the hair was shaved from the head and the face, and a plaster cast was made of the head and the skull,” Ms Anderson says.

After bushranger Ned Kelly was executed in 1880, within hours waxworks entrepreneur Maximilian Kreitmayer was at the morgue taking a plaster cast of his face.

Astonishingly, Kelly’s wax head was on exhibit within a day of his execution, drawing huge crowds to Kreitmayer’s celebrated waxworks museum in Bourke St.

To find out more, listen to the interview in the free In Black and White podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or web.

See In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper every Friday for more stories and photos from Victoria’s past.