How bikie’s sniper death changed underworld scene

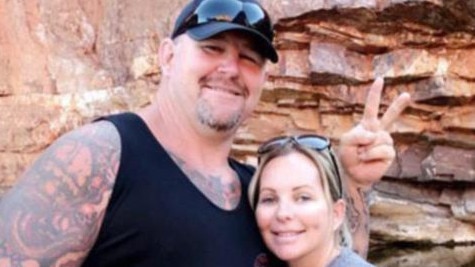

The execution of bikie boss Nick Martin in a very public place signalled a major shift in how organised crime operates.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A murder at a public venue in Western Australia last month should echo all over the country.

This is because it was a monumental shift in organised crime contract killing; the unknown hit man is clearly a professional sniper.

This is what we know. A Rebel motorcycle gang member, a marked man, went to the drag races on December 12 at Perth Motorplex, about 40km south of the city, with friends and relatives. A heavily tattooed man doesn’t stand out at the drag races; he stood there among the crowd.

Earlier that day, another man set himself up for a day at the drag races; he too had the perfect spot, in long grass 350m away from the action, waiting patiently, camouflaged and with a view of the track. It too was perfect for a sniper.

When the target showed up, it was daylight, noisy and busy with people. The Rebel relaxed among his friends and members of the crowd.

That’s when the other man got to work and set up his hi-tech, high-powered rifle and stand, made scope adjustments in fractions of a millimetre based on wind speed and direction, and then waited for two things to coincide: first, the target presenting clearly in the scope and second, a drag car to cause enough roaring engine noise to cover the “bang”.

Before squeezing the trigger, your breathing has to be just right too; this man needed just one shot to kill from more than 300m away.

The accuracy was incredible; Nick Martin, the outlaw motorcycle gang member of the Rebels, took a high-velocity bullet to the chest and died instantly. It went through him.

The murder was committed in broad daylight among hundreds of people. No one heard the shot over the drag car. They thought Nick had a heart attack.

So what does this have to do with Victoria? The border to WA had been reopened to eastern Australia three days before the shooting, which hints of a connection. Nonetheless, with all international flights cancelled, the killer is certainly Australian.

This modus operandi is in stark contrast to every other Australian organised crime hit that I have studied in recent times. It was methodically planned, using cover and camouflage, a long-range, highly sophisticated weapon only matched by the skill of its handler.

For decades Melbourne’s underworld killings have been ambushes, with victims often trapped, sitting in the driver’s seat of a car. The hit man — most likely armed with a handgun or shotgun — let fly from close range.

My statistical study of the 27 gangland executions known as the gangland war revealed a killing pattern with a distinct Melbourne flavour — hit men unintentionally leaving behind some telltale signs of where, when and how they are likely to strike.

But really, it’s the victim who unwittingly decides when and where they will be assassinated by their movements. The killer simply chooses the preferred option for them.

At least 90 per cent of the Melbourne killings were selective murders. It goes without saying that most, if not all, of these people knew their lives were in danger. Despite that, the victims failed to recognise the pattern that could have helped them avoid death or, at the very least, delay it.

But it doesn’t matter now, because one murder, 3500km away, has changed everything.

This killing has the hallmarks of someone with thousands of hours of practice or with professional or military training. I hope it isn’t the latter.

Internationally, political assassinations are often committed in a public place (42 per cent) mostly at long-range simply because of a lack of viable alternatives. But the circumstances of this bikie’s death seems more compatible to a killer who chose long-distance.

The statistics in Melbourne’s gangland war showed a remarkable 92.6 per cent were killed with a handgun or shotgun.

In the criminal world this means hit men are likely to come from short range or “up close and personal”. An astonishing 41 per cent of the killings involved victims ambushed while seated in cars — a sitting duck.

These statistics told potential victims in Melbourne’s underworld war they should avoid areas that provide cover for a close-range ambush. This is easier said than done living in urban areas, but some of the more obvious things to avoid would be dead-end alleys, corridors and small underground car parks.

Any would-be target must now avoid open areas or parklands near high-rise buildings or other long-range cover as well. And while it is always clever to avoid any routine of coming and going, I wouldn’t recommend being the person who puts out rubbish bins or walks the dog when a sniper is in the mix.

It goes without explanation the traditional Aussie hit man prefers the cover of darkness, empty streets void of potential witnesses and minimal traffic for a clean, uninterrupted escape.

Not so when you have camouflage, patience and the capacity to sit calmly in long grass waiting to take aim from 300m away. In fact, traffic noise, daylight and crowds are a bonus for a sniper.

Every resource must be thrown at finding this killer, lest our politicians and public officials get used to wearing flak jackets.

Simon Illingworth published an article in 2008 that correctly predicted the time, day of week and method of Melbourne’s gangland murders. He specialised in homicide and anti-corruption work as a Victorian detective.