Australia faces tough choice in its fight against coronavirus

Do we keep slowing the coronavirus and become more vulnerable when lockdowns are lifted, or should we let the virus spread enough so that some immunity is developed? This is the “wicked choice” Australia faces, writes Tom Minear.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There hasn’t been a lot of good news so far this year.

But Prime Minister Scott Morrison had some to report this week.

The growth rate of new coronavirus cases in Australia had fallen rapidly, he said, and it had slowed “well beyond our expectations” so that tens of thousands of people had managed to avoid the deadly disease.

And yet, just when things seemed to be looking up, there was an unspoken asterisk on Morrison’s positive remarks.

The perverse truth of this pandemic is that it is possible for Australia to be too successful in our response.

We are obviously lucky not to be in the position of places like Italy, where doctors have to consider rationing ventilators for people below a certain age, or New York, where makeshift morgues are overflowing.

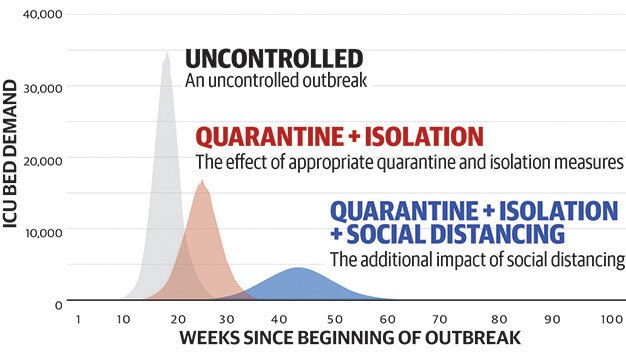

Modelling from Melbourne’s Doherty Institute this week showed the bullet we have so far dodged — 23 million Australians infected by an uncontrolled outbreak, 35,000 needing intensive care at the peak, and hospitals only having room for 15 per cent of those patients.

It predicted quarantine, isolation and social distancing measures could reduce community transmission by a third, meaning everyone who needed an intensive care bed would get one.

Those unprecedented guidelines mean we have so far managed to “flatten the curve” and slow the spread of the virus, but how we defeat it rests on what University of Melbourne epidemiologist Tony Blakely calls a “wicked choice”.

If we keep slowing the virus, we become more vulnerable when lockdowns are lifted. But if we allow it to spread more quickly, it can get out of control and more people will die.

This dilemma is best explained by considering the normal flu season.

When winter rolls around, we don’t shut pubs, close classrooms or stop playing football. Instead, we protect those in aged care, we get vaccinated and we let the virus run its course.

A lot of people do get sick — there were 65,000 confirmed cases here in 2019 — and the flu does claim lives, with 150 Victorians dying last year.

The truth is that this is the price we have been willing to pay to achieve herd immunity, where enough people become resistant to the virus that it cannot keep spreading.

The coronavirus is different. It is about twice as contagious as the flu, meaning it spreads much faster and puts far greater pressure on the hospital system.

On the evidence so far, it is more deadly. And it does not have a vaccination, and likely won’t for a year or more, which means creating that artificial level of herd immunity is impossible.

Well, almost impossible. A critical question now facing Morrison and the national cabinet is whether they are willing to let the virus spread enough that some immunity is developed.

Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy hinted at this quandary this week, when he described Australia’s current strategy “to identify, completely control and isolate every case”.

“That may be the long-term strategy. But we have to look at all of those potential options. There is no clear path,” he said.

Continuing to copy Wuhan — the epicentre of the virus — by trying to completely eradicate the virus would leave Australia without “any immunity in the population”, Murphy pointed out, and would mean keeping the borders closed for a very long time.

As an island, that is Australia’s natural advantage. But as Morrison chimed in, the nation’s leaders also need to keep the country running.

The $130 billion wage subsidy package, doubled welfare payments, loan holidays, rental relief and business cash injections are finite measures which are not sustainable if lockdowns are extended and tightened to eradicate the virus.

And even if we could afford it, how could Morrison in good conscience open the borders again, knowing how the virus is ripping through most other continents?

The alternative, which will be considered over the coming weeks and months, is to start relaxing some of the restrictions on our day-to-day lives to see how the virus reacts.

New South Wales is already talking about cafes and restaurants letting diners back in next month. But it’s easier said than done.

Even if the number of new cases dries up first, it would only take one infected person wandering back into their reopened local pub to spark another outbreak.

Morrison said this week that some states could trial tapering off restrictions, but that could — and likely would — be a decision that costs people their lives.

Our current contain-and-control strategy leaves little room for risk. Will Australians be willing to start gambling with the health of their loved ones?

And if we place that bet and lose, will we cop giving up our freedoms all over again?

Perfect is the enemy of good. But if we avoid complacency, and we keep social distancing and staying home, then our response might be perfect. And that won’t be as good as we would like to think.

READ MORE:

VIRUS HOT SPOTS INTENSIFYING IN MELBOURNE’S NORTH

HOW WILL HOUSING MARKET EMERGE FROM VIRUS?

WHAT TO DO IF YOU CAN’T PAY THE BILLS

TOM MINEAR IS NATIONAL POLITICS EDITOR