Dodgy ‘Thai massage’ parlours plaguing shopping strips across Melbourne

We’ve all seen them - the Thai massage parlours that have peculiar characters lingering around them and an air of lewd secrecy. So how are they left to spread across our suburbs like the plague?

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

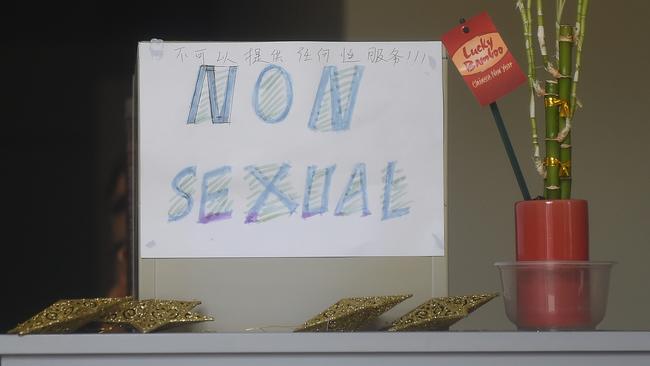

Scandals like the St Kevin’s saga get our attention. Meanwhile, rackets like the dodgy “Thai massage” parlours in every shopping strip are just part of the scenery.

We all see them. Until recently, three of these shady establishments were within 400m of our house. The closest one moved out the other day, probably chasing cheaper rent.

In the early evening, passers-by would see bored young Asian women studying their nails or their smartphones as they lounged around in the reception area.

Sometimes a hard-looking older man, not Asian, seemed to be checking the day’s takings. It’s possible, of course, that he is a respected member of the Society of Chartered Accountants and passes the plate at church on Sunday. But don’t bet on it.

When the place shuts for the night, well after shopping hours, a twitchy young guy in a tracksuit and baseball cap would arrive in a resprayed Nissan Skyline to pick up the “masseurs”. It’s possible he takes them to night school or netball practice. Don’t bet on that, either.

Across the railway line above a shop is another premises with the same cheap red electronic “Massage Open” sign they all seem to have. The folks downstairs complain that the upstairs tenants keep blocking the plumbing with wet-wipes. You can bet on that.

These dodgy parlours are as common as abandoned shopping trolleys in the Boroondara municipality, which has a town hall as big as the Taj Mahal and one of the biggest police stations in Melbourne.

But it seems policing massage parlours isn’t easy. Given the tricky legalities of proving what goes on behind closed doors, it’s easier to let sleeping dogs lie their heads off.

It’s the same all over. Police and council by-laws officers would rather turn a blind eye to the bleeding obvious than risk an unhappy ending in court. When it comes to policing a grey area, it’s easier for the thin blue line to give red lights a green light.

This is good news for the reptiles who have always been attracted to creaming easy money from the oldest profession.

In the bad old days of the 1970 and 80s, Lamborghini-driving pimps bribed bent cops to “protect” brothel rackets featuring bombings, shootings and heroin “hot shots”.

Sex workers would vanish down mine shafts or into the bay and no one knew anything, except those who weren’t telling.

The sex-for-sale business is more discreet now, maybe, but thriving in places it never used to exist. A former detective who lives in a bayside suburb and works in the southeast reckons he spots at least dozen massage parlours as he drives down the Nepean Highway.

He counts three in Chelsea shopping centre, two in Edithvale,

at least one each at Aspendale and Bonbeach. And that’s before you get to the rats’ nest at Frankston.

In Cranbourne, he says, there are four massage joints within 500m — two of them literally in sight of the police station.

No offence detected, apparently.

Before lawyers get agitated, let’s state that some establishments exist that provide only legitimate massage to citizens with aching muscles and sore bones. It’s possible a couple of such legitimate places are along the Nepean Highway.

Still, it’s clear that the same elastic law enforcement that tolerates flagrant drug-dealing around the “safe injecting room” in North Richmond is hardly bothered with mere massage parlours.

The injecting room debacle comes from a sincere attempt to tackle the realities of drug addiction. But it shows how hard it is to deal with the fallout from any sort of prohibition.

Banning anything creates an instant black market and undermines the law.

Exhibit A: “chop chop” tobacco and the branded contraband cigarettes that faceless people are importing with impunity and retailing around Australia.

Tobacco companies, which pay huge excise, are resigned to the fact that vans full of illegal tobacco do regular runs through country Victoria to replenish supplies at outlets in each town, from Mildura to Morwell.

For more sophisticated addicts who do not want to roll their own, there are contraband “tailor-mades” that look like the real thing but cost $12 a packet instead of $40.

There are pubs where hardly any patron who smokes has bought their tobacco across the counter. Why would they, when the illegal product is for sale everywhere at quarter the cost and no risk?

Through criminal stealth and official apathy, we’re falling into a new Prohibition era in which organised crime grows fat by breaking unenforced laws. “Victimless” crimes make perfect rackets because they combine low risk with high reward.

There’s a saying that those who don’t learn from the past are condemned to repeat it. Take the example of New York City, one of the world’s most dangerous cities in the 1970s. The zero-tolerance “broken windows” policy enforced there turned it into the safe city it is today.

But zero tolerance is out of fashion, possibly because it isn’t easy. It demands constant street-level policing to stop troublemakers getting away with minor anti-social offences that encourage more serious crime.

The bumper-sticker logic now quoted by critics of zero tolerance in government circles is that “you can’t arrest your way” out of a crime wave. Yet it seems that the cops who cleaned up New York did exactly that, concentrating on fare evasion, vandalism and petty theft along the way towards discouraging muggers, rapists and killers.

Leave windows broken and more windows get broken. Fix them and it cleans up the neighbourhood.

Police presence and prompt action made mean streets safe again. They still are. Citizens who had been frightened to use subway trains for a generation flocked back. They still do.

Some theorise that “victimless crime” doesn’t really matter and that policing it vigorously just victimises the already disadvantaged.

Here’s the opposing theory: organised crime exploits any soft spots to make a foothold for rackets.

Massage and tattoo parlours, strip joints, car yards and “security” firms can be used to launder drug money – or to subsidise drug manufacture or importation. They give gangsters a network and a shopfront in suburbs and country towns to mask more sinister operations.

Anywhere in Victoria big enough to have traffic lights, there are now so many drugs for sale that delivery is only a phone call away. Serious road crashes and violent incidents are now as likely to involve drugs as alcohol. Drugs sold by a network of predatory crooks operating under their own rules and with a war chest of dirty money to buy favours.

UNSUNG HEROES OF THE EAST GIPPSLAND FIRES

MOST MYSTIFYING COLD CASES OF THE DECADE

HOW BOB AND BILL’S STORY DESCENDED INTO HATRED

The former detective who counts massage parlours on the way to work also watches Comanchero outlaw bikies thunder past on semi-regular runs down the Westernport Highway to the Mornington Peninsula.

The gang’s sergeant-at-arms rides ahead to big intersections and brazenly blocks the cross traffic so the massed motorbikes pass through without stopping. And so on all the way down the highway.

Harmless? Or another example of the law being eroded bit by bit? Either way, a spooky reminder of the memorable line from Mad Max: “When the gangs take over the highways …”

That was a film. In real life, the story might not have a happy ending.