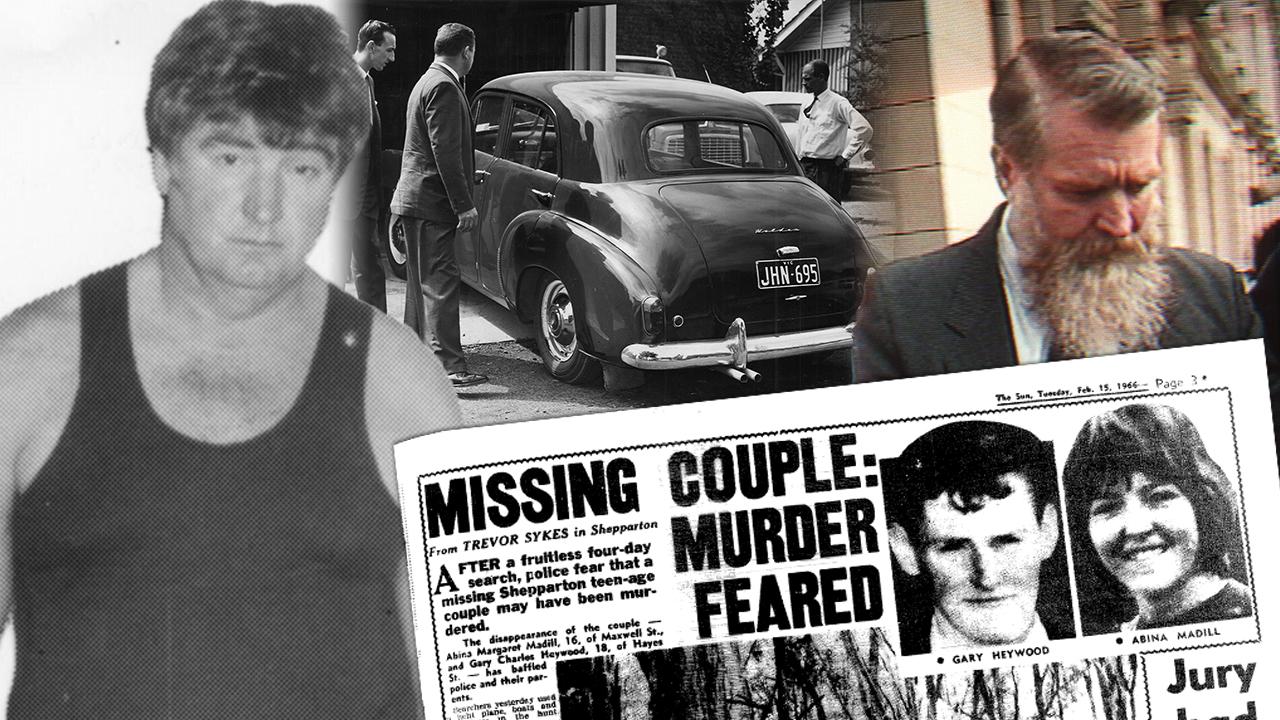

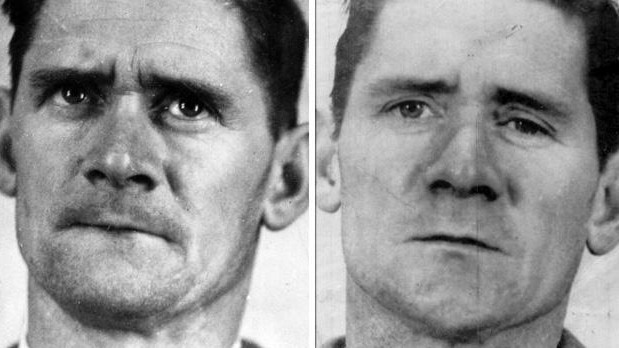

Peter Walker and Ronald Ryan most-wanted fugitives since the Kelly Gang

In 1965 hardened criminal Ronald Ryan plotted an escape from Pentridge Prison — Peter Walker made the greatest mistake of his life by joining him.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ronald Ryan would become the last man hanged in Australia — and Peter Walker was lucky not to be.

Walker was the tough youngster who went over the Pentridge wall with Ryan to become one half of Australia’s most wanted in the seconds it took for the older man to shoot warder George Hodson.

Once that happened, on December 19, 1965, the escapees were doomed, mainly because of their own rashness.

The defiant Ryan, a hardened crim at 40, insisted on having a beer at the Greyhound Hotel in St Kilda on the way to hide in an Elwood flat. No one in the bar called the police but that sort of solidarity couldn’t last, especially after the pair robbed a bank in Ormond days later.

Ryan and Walker were so “tropical” they didn’t need a price on their heads: any crook who needed favours from police, as most did, could bank on huge credit with one sly word.

A week in, the fugitives recklessly held a Christmas Eve party with a group of new-found friends, including knockabout tow-truck driver, Arthur Henderson.

Walker heard Henderson say that meeting the fugitives was worth something to him.

Suspecting the “towie” would betray them, Walker shot him dead in a public toilet after they went to buy beer.

Walker later claimed that Henderson attacked him viciously so he was forced to shoot him in the head in self-defence. But it reeked of an execution, more cold-blooded than the snap shot that killed the unlucky Hodson days earlier.

After two murders and a robbery in a week, the most wanted fugitives since the Kelly Gang scrambled to get to Sydney with an audacious plan to flee the country the way Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs had fled Britain just months before.

Walker would later say he believed police would kill them on sight unless they were arrested in a public place — which is what happened. After 18 days on the run, the pair were grabbed outside Concord Hospital.

The official line was they were to meet a woman whose daughter tipped off police. An alternative story, impossible to prove, suggests Sydney gangster Lennie “Mr Big” McPherson sold them out after Ryan asked him to organise false passports and a secret passage to Brazil.

That story (pushed by veteran crime writer Tony Reeves) goes that McPherson, in cahoots with corrupt Sydney police, thought it too risky to let the fugitives pull bank robberies to finance their exit plan. On form, they would shoot citizens or police, which would be bad for business.

And so, that story goes, McPherson cut a deal with corrupt cop Ray “Gunner” Kelly to set up the escapees for an easy arrest.

But if McPherson didn’t sell them out, it’s possible Walker himself tipped off police to ensure a public arrest that guaranteed handcuffs instead of hearses.

If that was the case, the secret died with Walker last weekend. Along with answers to other aspects of a violent and tragic life.

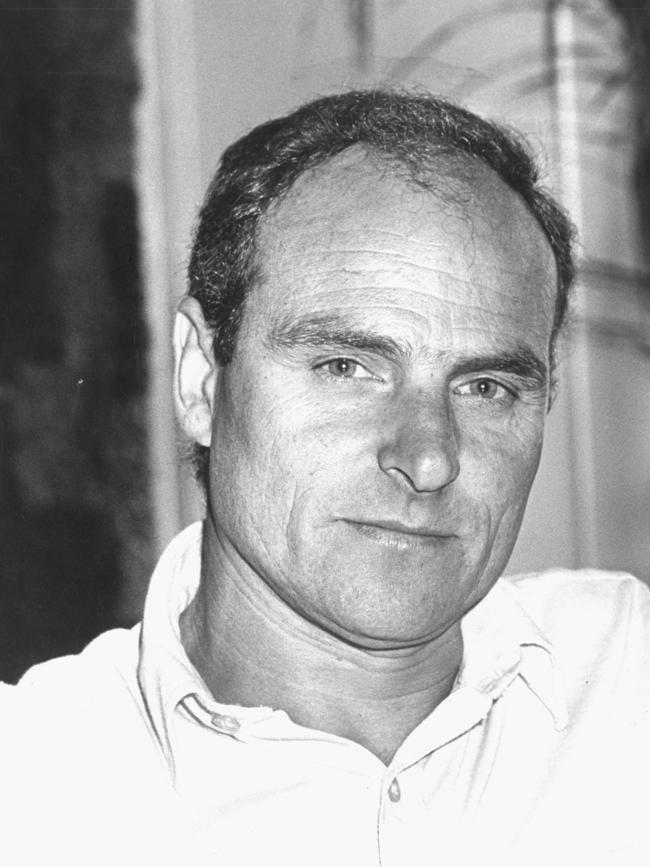

Peter John Walker was one of the lost children of the British Empire. When he died in hospital, aged 80, he was technically in custody of Australian Border Force — which was trying to have him deported to England, his birthplace.

Walker was shipped to Australia in 1949, aged eight, with his brothers, Derek and Brian. Even before that, he’d spent time in orphanages.

The boys’ father Robert Walker, a Queen’s Regiment soldier, abandoned them after their mother Alma gassed herself in their flat early that year, depressed because her drunken husband abused her.

Derek was 12, Brian barely 4, when the boys were put in Anglican boys’ homes. In St John’s, in Canterbury, and its sister institutions they risked the systemic abuse that would result in the home ultimately being named along with others where children were physically, emotionally and sexually traumatised.

Derek would marry young and join the police. But Peter, like so many other boys’ home kids, drifted into crime after being exposed so long to older offenders and harsh treatment.

He went to Balwyn State School and Richmond Tech before going to a training farm at Tatura at 14, then working on a dairy farm.

Like many of his peers, he started by stealing cars and burgling. He was sentenced to a month’s jail and fined at Cobram for “illegal use” of a car in 1958. At Kilmore in 1960, he got a three-year suspended sentence for stealing a car and an unlicensed rifle. He moved to NSW and more crime, doing two years in Long Bay before being released in 1962, aged 21.

For a while, he lived with big brother Derek and had a series of jobs in Melbourne’s western suburbs. But when Derek and his young family moved to Doncaster, Peter lost his way and started punting madly, running up debts.

He sealed his fate when caught robbing a Brooklyn bank.

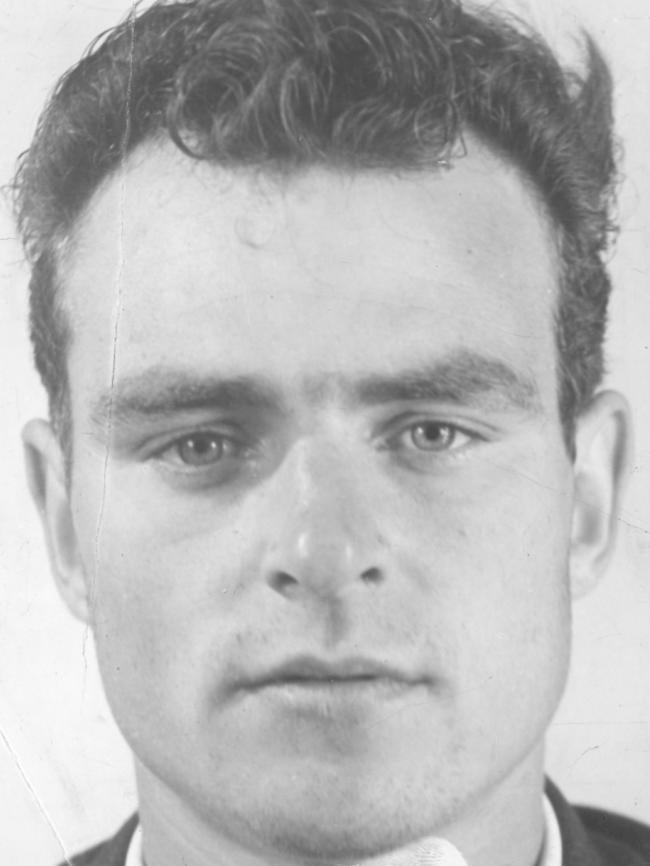

At 23, he was good looking, lean and fresh faced. A former prison officer recalls he looked like a young Clint Eastwood with a dash of James Dean, sporting a rocker quiff above a square jaw, long nose and sharp blue eyes.

But, under the handsome veneer, by the time Walker was sentenced to 12 years for robbery he was a damaged veteran of institutions.

He made a willing apprentice impressed by Ronald Ryan the hard man, a former kangaroo shooter and sleeper cutter with a long criminal record.

Ryan, too, had come from an institution with a sinister reputation: the Salesian Brothers school at Sunbury. In 1965, he was plotting an escape and Walker made the greatest mistake of his life by joining him.

By the time Ryan was hanged — despite a tidal wave of protests — on February 3, 1967, Walker was paying his debt the slow way in H Division, alias “Hell Division”.

A prison officer who knew him then, and later at Bendigo Prison, says Walker endured punishment so harsh it compares with the brutal 1800s convict era.

“No one did harder jail time than Pete Walker,” he said this week, an opinion echoed by a fellow inmate of the detention centre where Walker was held after being released from his last jail term.

As an old man, the close-lipped Walker revealed some of his ordeal: solitary confinement, regular beatings, one shower a week, drinking and washing in water from his toilet cistern.

“Hard labour” meant breaking rocks with a hammer, wearing as much or as little clothing as H-Division guards ordered.

Because Walker had been involved in a warder’s death, he copped beatings most days. He endured his ordeal stoically, never laying a complaint over often sadistic treatment.

After nearly a decade in “Hell”, he went to another division then to Bendigo to serve the rest of his long sentence for manslaughter, robbery and escape.

The officer who’d known him at Pentridge, Des Sinfield, was at Bendigo already. As the transferred prisoners stepped from the van, Walker greeted him warmly.

It was the beginning of an odd friendship between the tough ex-soldier and the tough crim.

In front of others, Sinfield was “Boss” or “Sir” and the prisoner was “Walker”. Chatting privately, Walker did Maxwell Smart impersonations and cracked jokes. He called Sinfield “Max” and Sinfield called him “Siegfried” or “The Nose”. Walker was a good tradesman and Sinfield assigned him “trusty” jobs.

If they went outside to do community service jobs, Sinfield would take him to his family home for morning tea.

“He was always clean and respectful and very polite to my wife. She would bake cakes, stuff he never saw in jail,” Sinfield recalls.

“He was highly intelligent and well read. I would have given him a job doing anything.”

After Walker was released around 1984, he visited Sinfield’s house with the woman who would become his lifelong partner, keen to show he was making a fresh start. Sinfield wasn’t home and it was a long time before he saw Walker again.

Once, Sinfield was unloading rubbish from a trailer at Eaglehawk tip when a car parked nearby and a familiar figure appeared, carrying a shovel. He shook hands and jumped on the trailer to help finish the job.

Walker was reputedly a model stepfather to his partner Fay’s children and, unlike most crims, not afraid of work. He stayed out of prison until 2002 when he went inside for theft and cultivating cannabis at Kyneton, where he ran a fruit shop.

In 2014 he was arrested on deception, drugs and firearms offences and sentenced two years later, aged 74, to seven years with a non-parole period of four years, four months. He could have got less time by informing but would never break the code.

By the time he was due for release, the Government wanted to deport all overseas-born offenders who didn’t have citizenship. In Walker’s case, this was bureaucratic bastardry.

He was old and very ill. His only home and only family were in Australia. He knew no one in Britain.

He and his brothers had been sent to “the colonies” to get them out of the way.

The sad truth, in their case and too many others, was that there was no better alternative.

One story the dying Walker told a fellow detention inmate about his younger self was that in the 1980s he and another “good crook” burgled a big-time bookie’s home.

They knew the bookie was out of the house and that his wife was at work. But apart from finding $55,000 cash, they were shocked to see a crying baby girl in a cot upstairs.

The baby’s nappy was soiled and wet. Walker’s story was that he changed her nappy and took one of six bottles of milk formula in the fridge and fed her.

Then, he said, he took lipstick and wrote on a mirror above the mantelpiece words to this effect: “If you ever neglect or leave that baby again, we’ll come back and kill you.”

It sums up, says the friend, both sides of Peter Walker, the abandoned child scarred by life but never scared of it.

“Sadly, he treated the system with the same callous disregard that he had been given since the age of eight.”