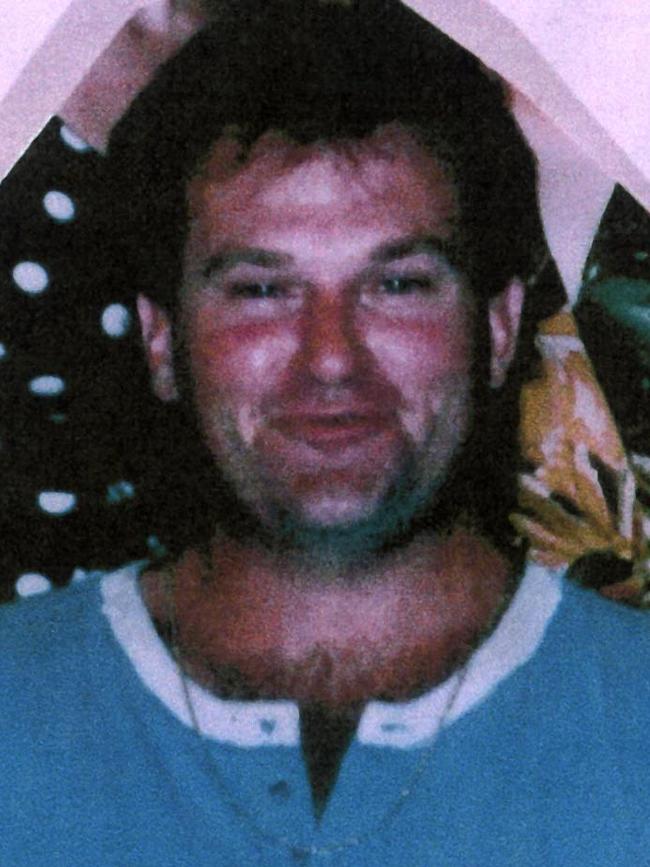

Lifelong criminal James Weston confirmed what his mafia paymasters must have suspected

A career crook caught up in a massive drug bust implicating the Calabrian mafia ’Ndrangheta has walked free after a suspiciously short stint in jail.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

James Weston, as Rodney James Stanley called himself last time he was arrested, got out of jail just in time for Christmas.

That was intriguing, as it meant the career crook served just over three years for his part in a massive drug bust implicating the Calabrian mafia, ’Ndrangheta.

For a lifelong criminal like Weston, the sentence was so light it no doubt confirmed what his mafia paymasters must have suspected when the handcuffs clicked in 2018: that he’d sell them out in a heartbeat.

All of which supports the proposition that there’s precious little honour among thieves. When the questioning gets tough, most crooks are pigeons in search of a stool.

Police believe that most crooks stand over or even kill older or weaker people they fear might inform on them, but will themselves instantly “roll over” at the clang of a cell door.

Weston could have faced up to 14 years in jail for his part in trafficking more than 400kg of cannabis from Adelaide to Darwin for syndicate boss Giuseppe Romeo, but served barely three. Go figure.

There’s not much to like about Weston or his father, Geoffrey Stanley. No wonder Finks bikies bashed Weston half to death, leaving him permanently affected. That he was involved in the Territory’s biggest cannabis haul proves even the mafia can’t get good help.

The Mr Big in the cannabis case, Giuseppe “Joe” Romeo is the son of a notorious mafia boss, Bruno “The Fox” Romeo, who dodged arrest for most of a long career heading the South Australian cell of the ruthless “Honoured Society” based in Griffith.

The old godfather must be rolling in his grave.

When a former Darwin crime reporter heard that Weston had slipped out of jail, he quipped “he might have gotten away with doing bad things to little people” but not with running errands for the mob.

That thought must irk Joe Romeo, who’s still paying for using Weston’s ragtag crew as hired help.

Romeo won’t be released until at least 2027.

By then, if there’s any justice, Weston’s sins might have caught up with him.

By mafia standards, he’s a bumbling bogan buffoon but police believe he and his father left a trail of suffering behind them.

Surviving relatives and friends of the old-time armed robber Aubrey Broughill agree. And they’re not the only ones grieving over the sinister fate of those who fell in with Weston and his father.

As armed robbers go, Broughill was a gentle soul.

To the detectives who arrested him, he seemed a likeable old rogue, which was why this reporter visited him in Pentridge Prison in 1988 to ask if it were true he’d pulled a string of bank robberies in his 60s to provide for his very young daughter.

He conceded that it was.

Broughill was, even then, possibly the oldest active stick-up man in the land.

He had started young, arrested for housebreaking at 12 years old in 1938 before moving through petty crime to the big time.

In 1961, he used a gun to rob a £4000 payroll from the Camberwell Town Hall.

That earned him eight years’ hard labour, which seemed to confirm his low opinion of hard work: as soon as he was released in the 1970s he went back to armed robbery.

The robber known to police and reporters as “the beanie bandit” pulled seven bank jobs (wearing his trademark green beanie) before an off-duty policeman saw him drive off from robbing a bank in North Blackburn in March, 1979, and took down the car number.

The armed robbery squad was waiting for Broughill when he got home. This time he got 15 years with 12 “on the bottom” but was paroled after seven years as a model prisoner.

By then aged 60, Broughill bought a .44 magnum handgun of the type made famous by Clint Eastwood’s fictitious cop “Dirty Harry” Callahan.

Again, he robbed seven banks (and a couple of building societies), supposedly escaping with $70,000 to put towards his little girl’s future. Even if that figure was not exaggerated by light-fingered bank staff and police, much of the cash was spoiled by a dye bomb, making it either unusable or dangerously traceable.

Inevitably, he was caught, by which time he had a new nickname, “Grandpa Harry”, in honour of the Eastwood character. He got 16 years with a minimum of 12 but was again released early for good behaviour.

Broughill led an unusual life outside prison. He told me he’d once been a boundary rider on an outback station and also a cook in a girl’s boarding school. But he always drifted back to crime.

When he was released in late 1995, he moved in with his younger sister in outer Melbourne. Almost 70 by then, he worked two nights a week at Victoria Market unloading trucks.

He could have made a living between odd jobs and the age pension but the call of “easy money” was too strong. This time he made the fatal error of teaming up with a crew of South Australian criminals.

That gang, of course, was led by Geoffrey Stanley and his son, alias James Weston. They pulled a string of thefts around rural Victoria and South Australia.

On Broughill’s 73rd birthday, January 12, 1999, Victorian detectives arrested him, Weston and Stanley and two others.

He was charged with 19 offences and released from St Kilda Rd police station the following day at 4am. No friends or family saw him again.

The strange case of the missing testicles

Quarry manager Reg Golding was looking at the flooded quarry behind a concrete making plant near Wodonga just after lunch on February 17 when he saw the body floating about 30m from shore.

The first detective at the scene noticed small turtles bobbing in the water near the body. When the corpse was landed, it was clear this was no swimming accident. The dead man was wearing a striped shirt and his jeans were caught on his left foot, despite the belt still being fastened.

In the jeans were a spectacles case and a wallet containing $208.90 and a driver’s licence and other cards in Aubrey Broughill’s name. Whoever or whatever killed him, robbery was not the motive.

Everything said foul play. There was no sign that Broughill had taken public transport to Wodonga and he hadn’t stayed in any local hotel, motel or refuge. He had almost certainly arrived in the area by car, but where was it?

Whoever had the car keys probably also held the key to a bizarre aspect of Broughill’s death: his body had no testicles, as if they had been cut off.

There was later some guarded speculation that the small turtles seen in the water might have nipped off the testicles.

The eastern snake-necked turtle has very strong jaws but no teeth and uses its claws to tear up carrion — but there were no claw marks on Broughill’s private parts.

The strange case of the missing testicles looked like the work of two-legged reptiles, torturing someone they were going to murder.

Five days after the body was found, Victorian detectives went to Geoffrey Stanley’s fruit block near Renmark in the Riverland to ask about Broughill.

Stanley seemed nervous but agreed to talk. He claimed that when the group had been released from St Kilda Rd nearly six weeks earlier they’d caught a train to Swan Hill then a bus to Mildura before being picked up by his other son, Scott.

Stanley said he drove Broughill 200km to Adelaide from Renmark (so he could catch a bus to Melbourne) because South Australian police would not let the Victorian retrieve his seized Ford ute. Stanley volunteered that Broughill was unsteady on his feet and often tripped up. As if, he seemed to suggest, the old robber might easily fall and drown.

The investigators knew it was true Broughill had got to Adelaide on January 14, because they found he’d gone to a doctor there and had a prescription filled.

When the police caught up with Stanley’s son, James Weston, he refused to answer questions about Broughill. Detectives concluded he had strong reasons to stay silent.

While Weston, Stanley, Broughill and others had been arrested for a string of thefts, a separate police investigation, codenamed Operation Jarrah, was chasing far more sinister matters.

In fact, investigators were looking into four men linked to the same Adelaide-based drug ring who had died over seven years.

In each case the victims were drifters without strong family connections, much like the wandering Broughill.

There was the disappearance in 1998 of Adelaide man Leo Joseph Daly, 33, whose body has never been found but is thought to have been shot and dumped at sea.

Weston and his father were arrested for Daly’s murder in 1999 but the charges were dropped for lack of evidence.

Police were also probing the deaths of three more men. Juan Phillip Morgan was just 17 when he vanished in 1992; David Michael McWilliams, 40, disappeared in 1998, and Robert Stanley Prendergast, 32, went missing in 1999.

All four had one thing in common with Aubrey Broughill: each had been closely associated with James Weston and his father.

Of course the Herald Sun is not suggesting they’re guilty, only that there are reasonable grounds for suspicion.

The difference with Broughill was that his body turned up. The police never believed for a moment he’d drowned accidentally. Neither did his grieving sister, Beverley.

She recalled her older brother as fit and agile for his age. “He didn’t drink or smoke and was a very strong man.”

What’s more, Beverley said, Aubrey was “the strongest swimmer I have ever seen”. She described him diving into the Yarra, where he “would glide through the water like Johnny Weissmuller.”

The man might know more about what really happened to Aubrey Broughill is now back on the street.

Still behind bars is the mafia boss with several more years to think about how things turned sour and why.

It won’t shock certain people if the stool pigeon ends up sleeping with the turtles, too.