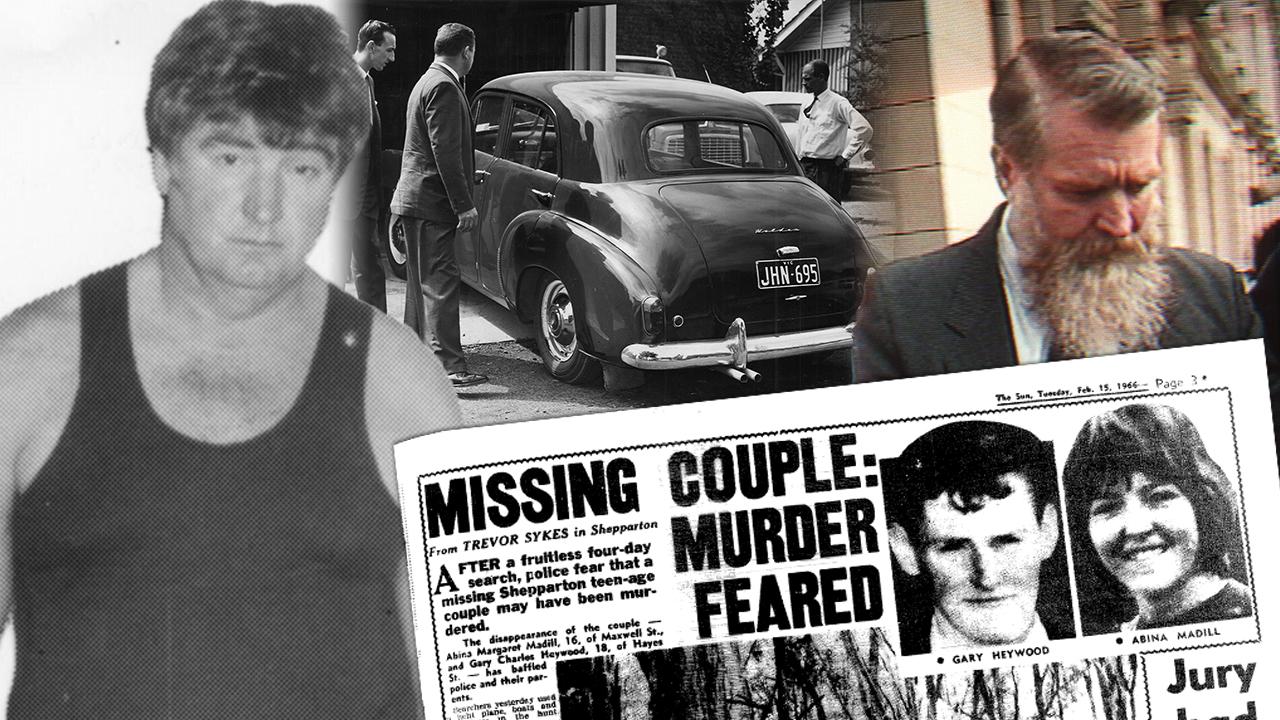

How “wheel man” Joey Hamilton and folk singer Shirley Jacobs were hounded by rogue police

The annals of Australian true crime history aren’t filled with too many romantic tales. But one of the most sweet – and violent – is the ballad of Joey and Shirley Hamilton.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Two-year-old Ilse had just toddled up the hall to get into bed with her parents when the bomb went off. It was a miracle she wasn’t near the glass panes in the front door when the shockwave blew them in.

In the split-second it took for the house to be showered in shattered glass, Ilse’s mother Barbara instantly pulled the doona over the child’s head and rolled her body over her.

It was an hour before dawn on August 1, 1978, in Station St, Carlton.

A lifetime later, Ilse’s calm, guitar-playing father Graeme Brookes remembers it clearly.

“I wasn’t thinking and stuck my head out the broken window and saw Percy Jones across the road and said ‘We’ve been bombed!’ and he said ‘Mate, turn around and look at the house next door to you’.”

Jones, the Carlton premiership ruckman and popular publican, was right.

Apart from all the blown-in windows, corrugated iron from the veranda roof of the neighbouring house had been blown down the street, along with plaster, broken bricks and glass.

Television reporter Iain Gillespie, quickly on the scene, was horrified to see it had blown a crater in the concrete porch of the target house. It was only dumb luck that his friends inside were not hurt.

It was clear that the bomb had been aimed at the odd couple who lived on the other side of the Brookes’ party wall, a brick width away.

Collateral damage is a big risk when a bomber targets someone living side-by-side with other families. But that didn’t stop the detective who’d detonated the gelignite that morning, or the one who’d driven him there.

Welcome to policing, 1970s style.

By the time lights and sirens reached Station St the three people who’d fled the crime scene were elsewhere, twitchy after an escapade that could have ended in bloodshed.

One of the three was a reporter who’d not long arrived in the city and had befriended detectives at Russell St who drank at the nearby City Court Hotel.

Joining a secretive dawn “raid” had seemed a good idea. The reporter hadn’t realised until too late he’d been suckered into a rogue mission loaded with danger.

At best, it compromised him, which was probably the detectives’ plan. At worst, it could have caused the death or injury of innocents.

This is what happened.

Not long after 4am an unmarked car idled along Station St past a particular terrace house with particular tenants hated by particular police.

The driver parked up the street. His partner slid out, a package under his arm. He returned quickly and they drove off.

Seconds later, the fuse hit the detonators and the gelignite he’d set against the front door exploded. The blast was heard right across Carlton.

The door of the target house was blown off and the blast sent a shockwave down the hallway, smashing furniture and knocking the residents’ German Shepherd dog unconscious, throwing his body the length of the hall.

If the bomb had killed someone the same way young constable Angela Tayor had died of injuries from the Russell St bombing a few years later, it might have been labelled a terrorist act and blamed on someone else. Exactly like the fatal Sydney Hilton bombing, set up by rogue police and blamed on a sect.

As it was, the Carlton bombing was a mystery. Officially, it still is. At the time, senior police promised straight-faced it would be investigated like any other crime. It wasn’t.

One problem was that the “okay” for the bombing had come from the Crime Department head, Chief Super. Phil “Fat Harry” Bennett.

The reporter in the bombers’ car, long since retired, told me last week: “Fat Harry was totally corrupt … he gave them the nod.” Meaning that dirty detectives had “a green light” to wage a dirty war against the people who lived in the Station St house next to little Ilse’s parents.

The couple under attack were Joey and Shirley Hamilton, known by sight and reputation to their neighbours.

The Hamiltons had nails placed under their tyres, rubbish bins emptied over the street, and their house repeatedly broken into under the guise of police searches. All part of round-the-clock surveillance involving three shifts of police a day.

The night before the bombing, the couple had been abused by detectives drinking at Lord Jim’s hotel in North Fitzroy.

The Hamiltons’ life had an edgy outlaw tone because of Shirley’s protest activism combined with Joey’s colourful criminal history. He was (or had been) reputedly a getaway driver disliked by police for refusing to “do deals” in the form of bribes or information, and then had the nerve to give evidence of corruption to a Board of Inquiry.

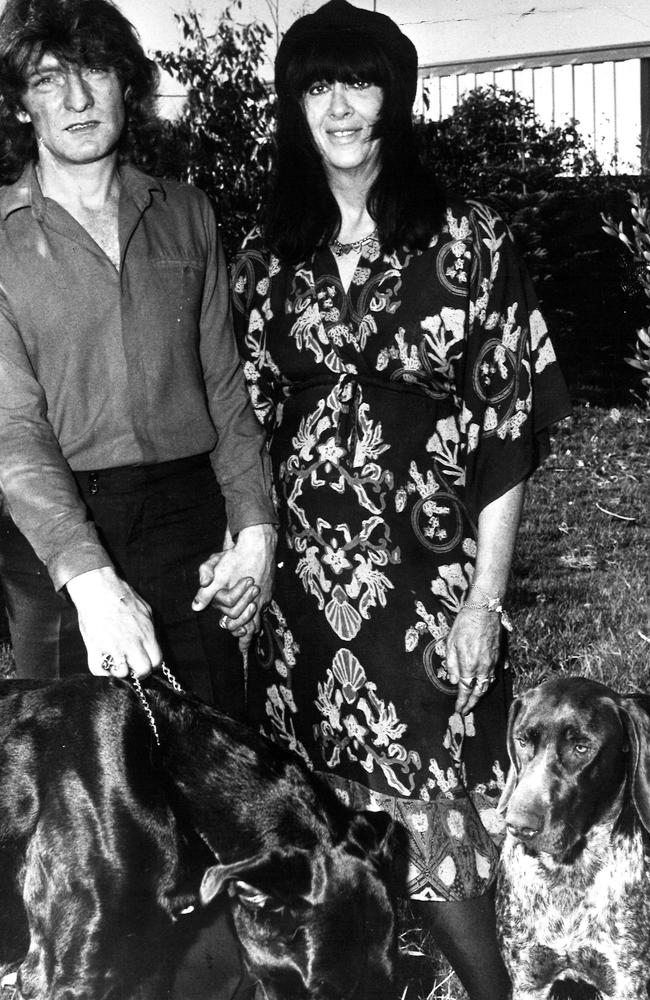

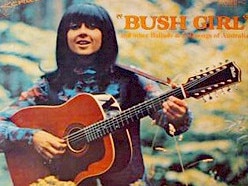

They were an odd couple, the ruggedly handsome 38-year-old criminal and his bohemian intellectual partner, a good folk singer and songwriter who performed under her previous name of Shirley Jacobs.

There was a touch of Bonnie and Clyde bravado about them, amplified later when they literally went on the run (to avoid being tried on a trumped-up drug charge) following the subsequent arson of their next house, and a car, near Ballarat in September 1979.

The 13 months between the bombing and the arson were filled with non-stop harassment. The Waubra house was damaged several times in the months before it was torched. Police denied wrongdoing but one of them dropped his diary in the driveway.

Prison chaplain Father Brosnan relayed a death threat he’d heard against Hamilton while talking to certain police at Warrnambool races.

The Waubra arson was even more sinister than the bombing, as it was on a remote property with no witnesses. The Hamiltons had gone to Melbourne with a friend, leaving their car at the house, giving the impression they were home. Both car and house were torched in a fire that might have killed them if they’d been there.

How or why Shirley Hamilton coped with the fear is hard to know, except she was stubborn and had a fierce sense of justice.

Shirley was 15 years older than the charming crook she’d first met when she played a gig in Pentridge Prison before he was controversially set free in late 1976.

It was Hamilton’s evidence to the inquiry headed by Queens Counsel Barry Beach that made him and Shirley targets of the brazen campaign that was either ignored or dismissed by senior police as underworld infighting.

Beach was an honest lawyer trapped in an unequal struggle with a “brotherhood” that condoned bent police lying under oath and intimidated honest colleagues into silence.

Beach would recommend charges against 55 officers. But only three were charged — and they were acquitted, a fact that speaks for itself.

In fact, one of those adversely named was given a Chief Commissioner’s commendation and several were promoted despite Beach’s findings, which suggests the police hierarchy treated the inquiry with contempt.

The Hamer Government didn’t have the will to impose itself on a force that could strike or take more devious actions against politicians and judicial figures.

Barry Beach’s one “win”, if it can be called that, was to expose the complete fabrication that had put Hamilton inside for eight years for an armed robbery he didn’t commit: that of a Thornbury milk bar in 1973 that had, in fact, been committed by the police informer and career criminal (Eric Grant, alias Heuston) whose false testimony put Hamilton behind bars.

The deal was for Grant to “walk” if he lied on oath that Hamilton had been in the robbery.

Beach heard evidence from the relatively few complainants and witnesses who were not intimidated into silence, and cross-examined dozens of recalcitrant police about alleged or actual wrongdoing. He was undermined by devious minds in a force used to getting its own way by hook or by crook.

Forcing Hamilton’s release in 1976, albeit under a politically-expedient early parole, was as close as Beach got to a just result. Hamilton was not pardoned or granted a retrial to clear his name, just put back on the street with a target on his back.

But when Hamilton married Shirley Jacobs he achieved a sort of fame for the alliance between two groups of outsiders: the underworld and the Left-leaning counter culture.

Hamilton had graduated from boys’ homes to street crime to prison to serious crime. A senior policeman, Paul “the Golden Greek” Delianis, once told me once Joey was known as a “wheel man” for armed robbery crews that raided payrolls and banks in the days when cash was king and security wasn’t.

It was the golden era of armed robbery and Hamilton had reputedly played a part in a dangerous game that involved violent men on both sides of the law.

What made him different was his lasting relationship with Shirley, a middle-class activist regarded by police and establishment types as something between a nuisance and a dangerous radical.

Shirley had been born Shirley Gilbert at Euroa, where she was a bright child, good at reading and writing. Her first marriage was to a respectable young Melbourne dentist, Horst Jacobs.

For Shirley’s daughter Debbie Jacobs, her mother’s latest (and last) relationship was almost a role reversal. Here was her middle-aged mum behaving like a runaway teenager with a crush on a bad boy.

For years, Debbie tried to keep her distance but inevitably had to bail out her mother and her volatile partner. When the pair went “on the run” for months in 1980, Debbie lost the then hefty sum of $2500 that she had posted as bail.

The Hamiltons did television interviews from secret hideaways and were eventually arrested. But it was clear that the story of the bombing and the fire and death threats had entered the public consciousness.

By the time John Cain’s Labor Government took power in 1982, the worst harassment ended. Hamilton could point at Beach’s finding completely exonerating him for the Thornbury robbery and demand compensation for being wrongfully imprisoned for more than three years.

It so happened that an innocent man wrongly locked up for one night received $2000 from the State. At that rate, as newspapers pointed out, Joey Hamilton was entitled to more than $2m, so his subsequent demand for more than $1m was fair.

But Premier “Honest John” Cain, most reasonable of men, was caught between pro-Hamilton opinion among his party’s union members on one hand and the trenchant opposition of the Police Association on the other. He struck a secret deal to pay Hamilton $26,000 that didn’t stay secret.

The $26,000 was a fraction of Hamilton’s original demand but enough, then, to buy a cheap house. The Hamiltons owed so much to lawyers they didn’t even repay Shirley’s daughter the $2500 bail they owed her.

They drifted into anonymity but stuck together. When Shirley was dying in a Thornbury nursing home in 2015, Joey Hamilton came to see her every day.

Graeme Brookes, the Dylan-loving neighbour from Station St, wrote a song about them after the bombing. He called it “The Ballad of Joey and Shirley.”