How a simple twist of fate led Deb Gray to become a rebel with a cause

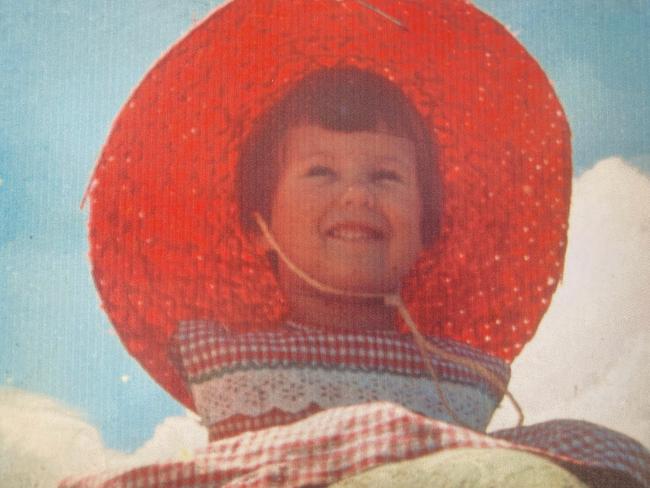

Deb Gray was born with no arms and tiny deformed legs amid suspicions her mum — and many others — were medical guinea pigs. But she has been determined to live a life of courage.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A conflict of interest is OK if you declare it upfront. Deb Gray and I were born in the same country hospital a few weeks apart and I’ve known her, or about her, pretty well ever since.

A lot of East Gippsland people can say the same. Deb got people’s attention. That happens when you’re born with no arms and with legs so short that your feet are where most people’s knees are.

Deb’s father Ray was a trawler fisherman who later drove timber trucks. Deb’s mother, Cammie, was well liked by everyone around Lakes Entrance.

Their lives changed forever on the hot January morning that Deb was delivered. She had no arms, tiny deformed legs — and the possibility of brain damage.

They were urged to put the baby in an institution and forget her. They refused.

“She’s our little girl and we’re taking her home,” her mother said. And they did, taking her back to their house in Lakes Entrance, half an hour east.

It was an act of love and courage for which Deb has always been grateful but her parents didn’t see it that way. They took the hand fate dealt and got on with it.

The fisherman’s daughter seemed a textbook example, later, of the most catastrophic form of injury inflicted by the German-made morning sickness drug thalidomide, revealed in 1961 as responsible for thousands of deformed babies around the world.

But Deb had been conceived in mid-1956, before the drug was officially prescribed in Australia. Yet her defects were identical to those of certain “thalidomiders” born a couple of years later.

It was a mystery then and still is. It raises the question of whether off-market samples of thalidomide — or some other untested drug — had reached Australia earlier than 1958, the year it was approved in the false belief that testing must have been done in Europe.

There seemed no agreed reason for Deb’s injuries, nothing or no-one to blame. Everyone from the drug manufacturers and distributors to Australian authorities to the doctors who handed out samples of new drugs had a cast-iron motive to stay silent and minimise their liability.

Those were things the Gray family wasn’t equipped to tackle so they concentrated on looking after Deb.

Deb’s father took up driving trucks, delivering timber from the local mills “down the line” to Dandenong. As a toddler she would often perch on his knee at the wheel and was known in every truck stop along the Princes Hwy.

Deb went to school at Lakes Entrance Primary then to Bairnsdale High. I recall seeing her once at primary school, balanced on the backrest of an old wooden desk, holding an exercise book down with one foot and writing with the other.

Brave and fierce and focused, she could climb trees using her feet and her teeth. She had to survive in a world that wasn’t built for her.

It would be many years before she turned her mind to the reasons for the malign thing that had happened in her mother’s womb.

Deb’s mum, Cammie, had during her pregnancy used the same doctor in Bairnsdale as my own mother had. They were two young mothers among dozens of his patients from Bairnsdale to the border.

His name was Dr Stan Reid and he was a rising star in obstetrics, later leading the way in monitoring the unborn.

He would later work overseas and then took a position in Perth and became a renowned specialist. He also achieved another sort of fame by heading the Royal Perth Yacht Club during its America’s Cup yacht win with Australia II in 1983.

But that was later. In mid-1956, when Deb Gray and I were conceived, Stan Reid was a young medico starting out in Bairnsdale, a rather dazzling figure to trusting patients.

Reid was one of life’s winners. His father, Stan Reid Sr, had been a horse trainer, and had prepared The Trump to win the Caulfield Cup and Melbourne Cup double in 1937.

Stan Jr. went to St Bede’s College in Mentone and set himself for a different kind of career, leaving the racing world behind.

A lifetime later, Dr Stanley Reid AM was named in the St Bede’s Old Collegians Association Hall of Fame. The gathering was told he had “represented St Bede’s with distinction in almost every kind of activity.” This included his being college captain, dux, and captain of athletics in 1944. He also represented the school in football, cricket, tennis and swimming.

Young Reid graduated from Melbourne University in medicine and surgery in 1950. After working in Sydney for two years, then another two at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne, he married in 1954 and joined a practice in Bairnsdale as the doctor specialising in pregnancy and delivering babies.

Given the young doctor’s interest in obstetrics, it is natural he would attend conferences and seminars in the mid-1950s, at which he would meet overseas experts and be courted by international drug firms who pressed free samples of their product (and other largesse) on doctors.

It’s not a stretch to believe he subscribed to a wide range of “state of the science” literature in his field and would easily be able to import products not yet on pharmacy shelves. It’s hard to grasp now how much unquestioning respect, and obedience, that doctors, lawyers, priests and bank managers commanded in small communities in the 1950s.

In the new post-war world, a slew of new or re-purposed and renamed drugs and chemicals hit the civilian market.

The baby boomer generation had its hazards. It was the heyday of insecticides like DDT, herbicides like “agent orange”, stimulants like benzedrine and strong opioid derivatives and dangerous hormone and steroid products. Every farm and shed had deadly poisons in them, often used recklessly by those who’d survived war and had fatalistic attitudes baked in.

In East Gippsland, young Dr Reid was king of the kids — literally, in the sense that he delivered this reporter and Deb Gray and so many others.

The question is, what did he (and other doctors) deliver to pregnant women months before their babies were due?

Did they have access to uncontrolled and unprescribed drugs produced in Europe and the United States? If so, did they hand them out to patients?

At this distance, proof is difficult but the anecdotal evidence is strong, maybe compelling.

My mother has quietly insisted for more than 60 years that Dr Reid, unasked, gave her tablets for morning sickness. Habitually cautious, she flushed them down the lavatory rather than have them around the house.

Deb Gray does not know what tablets her mother might have taken but strongly believes Dr Reid gave her unprescribed products during her pregnancy.

At least two other women in Gippsland who were treated by Dr Reid during their pregnancies also had babies with birth defects, though not as catastrophic as Deb Gray’s.

I spoke with one of those people in 2012 (when researching the use of thalidomide). He told me his chest muscles had never developed, a known thalidomide side-effect if the drug was taken at a particular stage of pregnancy.

But the most compelling evidence came from the straight-talking Jackie Reid, in 2012 a well-known Perth socialite — and widow of the man who deservedly became such a respected figure in obstetrics and international yachting.

Mrs Reid told me without hesitation that, as a young doctor, her husband had innocently handed out sample drugs free in the belief he was helping pregnant women handle nausea and discomfort.

She knew this, she added candidly, because he had given her the same drugs. In fact, she said, she suspected that one such sample drug caused one of her own babies to be stillborn during their time at Bairnsdale.

Subsequent global exposure of thalidomide as a cause of birth defects made it the catch-all culprit for a range of defects, ranging from stillborns to truncated limbs to lack of muscling.

It is hard to know whether the thalidomide catastrophe obscured the origin of defects possibly caused by other chemical compounds. But we can be certain that big drug manufacturers who casually “market tested” drugs in remote markets through a network of willing doctors would do anything to avoid admitting liability.

The cruel arithmetic for Deb Gray and a few others like her is that thalidomide was not legally available by prescription in Australia until 1958, meaning there is no legal remedy for them.

It’s clear that, even after the 1961 scandal, thalidomide was still available in many places around the world, and stayed that way in some places until the 1970s.

What is not clear is whether early samples of potentially damaging drugs were simply mailed from overseas or handed to doctors from 1956 to 1958.

On the evidence of Dr Reid’s own wife and my mother and Deb Gray’s body, they probably were. But for Deb and her family, there was nothing to be gained by brooding. It was a case of getting on with life on her own terms.

Her parents and her brothers encouraged her to look the world in the face.

The result was a girl who was fierce about doing what everyone else did. As a teenager that meant hitting bullies with the heavy artificial arms she was forced to wear. Later, she listened to loud music, smoked and drank and rode on the back of motorbikes with the sort of boys her mother didn’t approve of. She was a rebel with a cause.

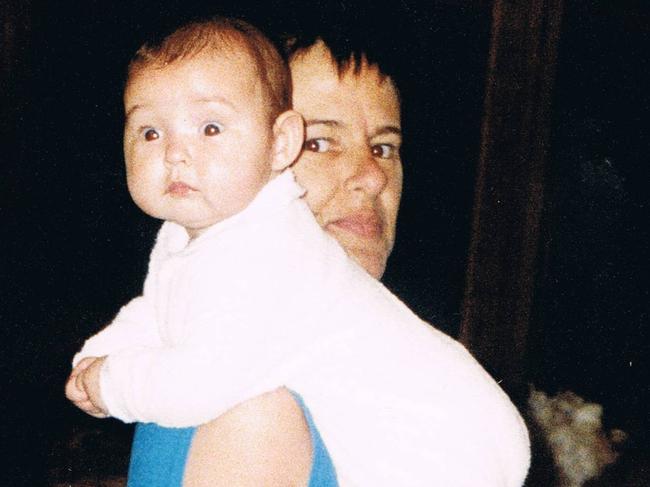

Her odyssey from Gippsland to Melbourne to the rest of the world then circling back to Australia and, finally, going home to Lakes Entrance, makes quite a story.

For years she thought she should write a book but she didn’t want to do it while her parents were alive because there were things they didn’t know about sex and drugs and rock’n’roll.

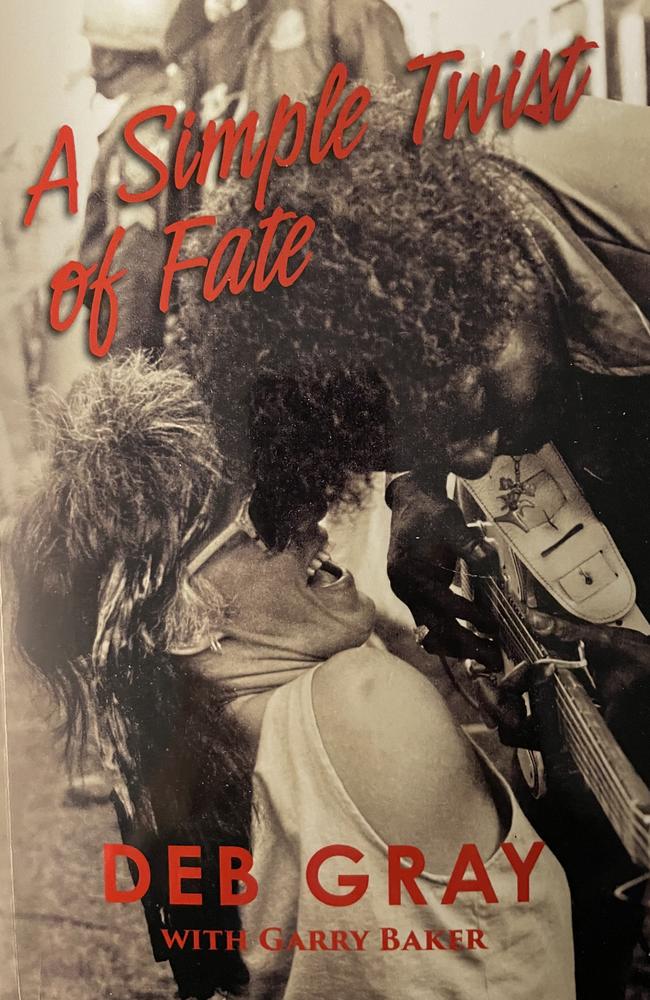

Now she has finally done it. The title is from a favourite Dylan song: A Simple Twist of Fate.

When the first print run landed in Bairnsdale this month, not far from the hospital where her story began 68 years ago, she had no idea if anyone would be interested.

But they came in dozens, queuing up and spilling into the street outside, waiting for her to sign copies.

That’s when that tough little woman cried.

Postscript: After leaving Bairnsdale, Dr Stan Reid became a pioneer of the ultrasound imaging system now in common use. It allows doctors to see if a foetus is developing normally and gives early warning of birth defects. It was an interesting choice of research.