Former Olympian Nathan Baggaley could skate around charges

Former Olympian Nathan Baggaley could “do a Bradbury” and skate around criminal charges.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The way a perplexed Anthony Draper put it to the Supreme Court in Brisbane, getting chased by a Navy patrol boat came as a great surprise.

Sure, he’d been flown up from Sydney to skipper an inflatable boat — but only to pick up “some smoko” near Coolangatta, he thought.

Imagine his shock, the seadog told a bemused prosecutor, a poker-faced judge and earnest defence counsel, when he was asked to drive the boat far across the ocean, all night — 360km, in fact.

There, he said, they met “a big red boat.” On it were a crew he described as “South American people, with guns.”

What a surprise. There were further shocks in store for Draper on that July day in 2018. Here he was thinking they were picking up marijuana or maybe smuggled tobacco but then he heard the South Americans mention “cacao” as they transferred the plastic-wrapped packages.

It was then, he said, that he wondered exactly what they were smuggling. Could cacao be cocaine? His “boss”, Dru Baggaley, told him not to worry and keep loading.

But worry Draper did when a fast boat chased them as they headed back to the mainland.

“I was shitting myself,” he told the court with feeling. “I thought they were pirates.”

But they weren’t. It was an Australian Navy boat, alerted by border surveillance aircraft that had already contacted water police.

The adventure ended when masked and armed police intercepted them 65 nautical miles off the Gold Coast, but not before Dru Baggaley was filmed dumping the black parcels overboard — nearly 600kg of cocaine, with a street value close to $200m.

On shore, meanwhile, police were watching Dru’s big brother Nathan, who seemed to be waiting for something or someone at the Brunswick Heads boat ramp.

Nathan had, after all, paid $107,000 for the inflatable boat and his fingerprints were on gaffer tape used to blank out its registration numbers. A good brother will do that. But so might a bad one, which is the basis of the case against the Baggaley brothers: Dru, described as a Coolangatta fishmonger; and Nathan, one of Australia’s finest international athletes.

The trouble with Nathan Baggaley, as his friends and former Olympic team mates might agree, is that as an alleged scallywag, he makes a wonderful kayaker.

As the court weighs up evidence implicating the three-times world champion and Olympic medallist, it’s possible he will “do a Bradbury” and get through his latest troubles — a caper that his counsel Anthony Kimmins described “like a script from a James Bond film, a game of cat and mouse on the high seas.”

The evidence against Dru Baggaley would appear fairly robust, given that seadog Draper is testifying against him and that Navy and police cameras recorded the action. The evidence against Nathan is more circumstantial, a good reason for him to be pleading Not Guilty, Your Honour.

But if the court decides the champ’s fingerprints are all over Operation Overboard, it will add more controversy to a chequered career — quite a fall for the man voted the Australian Institute of Sport’s athlete of the year in 2004, just before the tide turned against him.

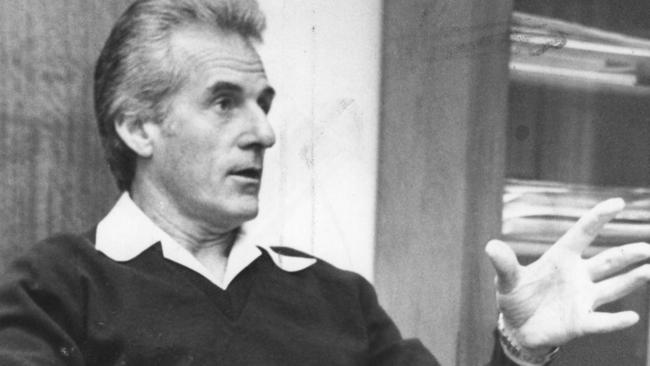

Baggaley was a terrific athlete. But, as alleged skullduggery goes, he isn’t in the same league as the teflon-coated Murray Stewart Riley, Olympic oarsman and bent copper.

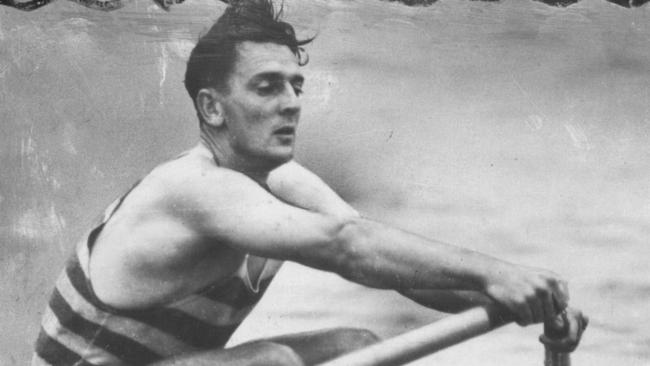

Riley joined the NSW police in 1943. He found time to train as a sculler with his fellow policeman Merv Wood, a world-renowned rower over 20 years who would rise to become the Police Commissioner despite a reputation for never making an arrest.

Wood and Riley won gold medals together at the 1950 and 1954 Empire Games, and Riley also represented Australia at the 1952 Olympics and took a bronze at the 1956 Olympics.

It’s interesting that Riley, sports hero and friend of the future Commissioner, an even bigger sports hero, thought it a good idea to pal up with two of the most notoriously corrupt policemen in the land.

One was Ray “Gunner” Kelly. The other was the sinister Fred Krahe, suspected of being enforcer and executioner for organised crime figures.

Riley went from winning medals for Australia in the 1950s to being booted out of the NSW police in 1962 to pioneering heroin importation in the early 1970s, being jailed in the early 1980s and plotting huge frauds in the 1990s before becoming an international fugitive.

The handsome and incorrigible Riley helped fellow bent cop John Wesley Egan run “the corset gang”, using female couriers who hid heroin in their foundation garments.

Corsets went out of fashion but heroin did not, and Riley later brought in plenty of it with a false-bottomed suitcase before branching into other criminal enterprises around the world.

Riley, an equal-opportunity crook, did business with Neddy Smith, Lennie McPherson and Roger Rogerson, the American Mafia, the Teamsters Union, the notorious Nugan Hand bank, rogue CIA agents and the IRA.

By the time his old sculling partner Merv Wood had taken over the top police job in 1977 (before retiring under a cloud in 1979), Riley was well-known to crime intelligence experts around Australia — and elsewhere.

One reason for this was that when Riley went to America, instead of taking in Disneyland and the Golden Gate Bridge, he met up with mobsters like Jimmy “the Weasel” Frattiano, the Santos Trafficante family and Teamsters heavy Rudy Tham.

In 1973, Riley avoided giving evidence to the Moffitt Royal Commission into organised crime, prompting Justice Moffitt to note acidly that the absent man was treated “with undue favour (by police)” despite being a priority target for the new Crime Intelligence Unit. That’s judge-speak for “The fix is in.”

Riley was an ideas man. One idea was importing 2.7 tonnes of cannabis, which went astray when a boat broke down off Papua New Guinea, causing the plotters to stash the cargo in a ship hulk while they made other plans.

The other plans became a yacht named Anoa, which was apprehended heading south in 1978 with the 2.7 tonnes of cannabis. The contraband was heavy but Riley’s sentence was remarkably light. He did only six years of a possible 17, all in cosy low security.

Still, Riley’s name had been tarnished, so he got a new one. By the time he got into trouble in England in 1990 for conspiring to defraud British Aerospace of $100m, his legal name was Murray Lee Stewart.

Even overseas, he seemed to have the magic touch. While his co-accused went to a proper prison, Riley was swiftly transferred to a country correctional facility. He walked out one day, wasn’t missed for seven weeks and wasn’t caught for eight — touring Ireland, Spain and Belgium before being recaptured on 31 January 1992.

Amazingly, he was again transferred to a minimum-security prison. There was no extra security despite his form. He escaped again in January 1993, taking part in a huge IRA counterfeit racket. The IRA’s ability to spirit wanted men all over the world — including Australia — was shown by the fact he got to Hong Kong and lived there incognito for months.

In early 1994, he flew to Australia and settled in Queensland. The authorities even gave in to his repeated applications for an Australian passport in his new name.

Meanwhile, a spokesman for the British Home Office suggested it would be “extremely unlikely” that Riley, alias Stewart, would be extradited to the UK to serve out his time. The reasoning being that he’d been found guilty of the “victimless” crime of conspiracy and the cost of bringing him back under police escort would be “exorbitant”.

Riley, ace of crooked cops, lived out a blessed life. He stayed fit and well and lived quietly under the radar. But sometimes those with sharp eyes and long memories would spy him strolling around that part of Queensland referred to as “a sunny place for shady people.”

When he died last year at 94, he was technically still a wanted man. For at least 50 years, he seemed to have a fairy godfather looking out for him on high. The Baggaley Bros should be so lucky.