Fickle loyalties put target on mad dog Shane Bowden’s back

Bikie Shane Bowden’s brutality left a trail of destruction, but when the past caught up with him on a Gold Coast street, his execution was a cliche straight from the manual of organised crime.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

On four legs or two, mad dogs don’t have a great life expectancy. The more dangerous, the more likely they are to be shot.

That’s how it went for Shane Bowden, the muscle-bound gym junkie among the first new wave bikies to ditch the Charles Manson look of unwashed denims, greasy leather, dirty hair and beard.

But, as a criminal, the clean shaven Bowden made a good bodybuilder, with more attitude than aptitude. The main reason he survived until age 47 was that he’d spent all but two of the previous 20 years in jail, safe from the repercussions of his unhinged steroid and amphetamine-fuelled violence committed outside.

When the past caught up with him on the Gold Coast last October, his execution was a gangster cliche: he got home at midnight in a regulation black BMW sedan after pumping iron and was mowed down with 21 shots from a machine pistol.

Police later found two burnt-out vehicles, torched getaway cars for a hit team of two — or possibly more.

Maybe there were two gunmen and a driver, or even a fourth player waiting with the second car. That two cars were torched means a third was planted. All of it suggests a conspiracy.

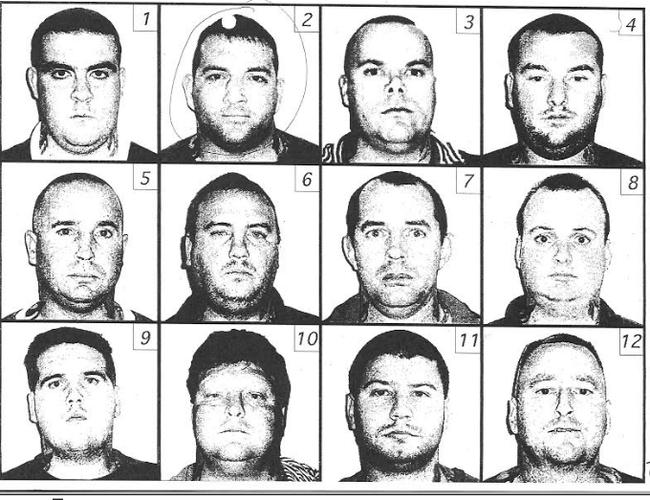

This week, police revealed they know when and where the two getaway cars were bought a week before the murder. They released footage of a silver Commodore and a maroon Falcon being driven from Ipswich towards Brisbane, days before Bowden’s last workout.

To publicise the breakthrough, there’s a $250,000 reward for anyone who might fancy cash instead of being charged as an accessory to murder.

Bowden’s execution was straight from the organised crime manual, and far more effective than anything he himself ever did.

The fact there was more than one attacker suggests it wasn’t a personal grievance — the regular “girlfriend trouble” — although Bowden always had those, as well. This seemed more like a sanctioned gang hit to liquidate a liability.

It happened in a cookie-cutter street in the Gold Coast suburb of Pimpana but it’s the sort of thing that happens anywhere from Cape Town to Canada, another blood-soaked chapter in endless gang wars.

It wasn’t a case of who had a motive to kill Bowden but who didn’t; he had nearly as many enemies as tattoos. He changed outlaw motorcycle clubs nearly as often as he changed bedmates. Such fickle loyalties can be fatal in the dog-eat-dog world in which he’d chosen to spend his adult life.

Bowden’s most recent club, the Mongols, led by Toby Mitchell, picked him up from Loddon Prison in Victoria in a limousine almost exactly a year ago.

Two weeks is a long time in bikie politics. Just 15 days after the limousine charade, Bowden copped a bullet to one knee in a drive-by shooting at Epping. It was probably more warning than murder attempt. He decided to head to the Gold Coast to recuperate from the battle of wounded knee.

The Gold Coast was where he’d first come to notice in the murderous “Ballroom Blitz” of 2006. Before that night, when a kickboxing tournament turned into a riot with guns and knives, Bowden was known only inside bikie circles, to a few police, and to those in the track cycling fraternity who recalled him as a champion junior rider in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

He had been born in South Australia – to a pair of 12-year-olds, according to court evidence – and was immediately adopted out.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, he struggled at school but was an early developer physically. He became a junior track champion training with the Australian Institute of Sport before injury killed his chances of getting to the Olympics.

Bodybuilding, martial arts and boxing gyms are places where a cross-section of people with similar interests rub shoulders. Among the tough tradies and bouncers, typically, are serving or former police, prison officers, customs officers and military personnel. And former athletes like Bowden, hooked on body building but no longer constrained by the necessity to be aerobically fit and “clean” to compete.

At 22, in Adelaide, Bowden had the elite athlete’s training discipline and ego but no legitimate outlet. World cycling was full of steroid users and abusers, and bodybuilding wasn’t much better. Then there’s the obvious link between “supplements” and steroids and illicit recreational drugs, notably amphetamines and cocaine.

Soon, Bowden was a Hells Angel “prospect” but, the story goes, he angered senior Angels and fled to Queensland, where he joined the opposition, the Finks. He and Nick “The Knife” Forbes became Finks enforcers with “terror team” stickers on the fuel tanks of their Harleys.

Bowden and Forbes became notorious for the “Ballroom Blitz”, where they started a very public riot that began to turn political and public opinion against outlaw clubs in Queensland. It was an act of lunacy that, step by step, led to his execution 14 years later.

The “Blitz” was an embarrassment for authorities because local police had mislaid warnings from interstate agencies that Finks members were heading north for a confrontation with the local Hells Angels. The whisper is that an officer forgot to relay interstate “intel” reports of the brewing trouble. It wasn’t the force’s only mistake.

Although 2000 people were expected at the kickboxing event on the night of March 18, only two on-duty police were posted there, whereas 18 were routinely assigned to mind 3000 spectators at a peaceful rugby league game nearby.

But police were not the only ones caught flatfooted.

The local Hells Angels chapter was complacent because it was the dominant club, skimming or running the usual crime rackets in southern Queensland.

The Angels had 20 members at the fight night, including two armed men in the crowd, and a “war wagon” of guns parked below. They were sure the Finks would have barely half that number and pose no threat.

They didn’t know that the Finks had called in dozens of reinforcements, which was why interstate police had tried to warn of a looming showdown.

Ultimately, gang wars are about “turf”, but in this case there was another spark in the fireworks: the young Christopher Wayne Hudson had defected from the Finks to the Angels. This embarrassed Nick The Knife, the heavyweight Fink who’d proposed Hudson’s membership.

Not only had Hudson reportedly borrowed a fellow Fink’s girlfriend but he’d switched clubs to dodge the fallout – a plan that dissolved when 43 Finks swaggered into the ballroom.

Older, wiser bikies know never to commit violence in public because it brings instant police heat. But the younger heavies, using the same drugs they dealt in, were so “tuned up” they ignored the fact that five cameras were recording everything.

Trouble began when Forbes, obliged to defend Finks honour, challenged his former protege Hudson to fight.

The Finks were there to back Forbes – and to maim or murder Hudson, who refused to be goaded into throwing the first punch. The two police and the promoter gamely stood near Bowden and Forbes to forestall the looming trouble, but Bowden couldn’t help himself.

He was wearing knuckle dusters, and threw one punch at the promoter, knocking him unconscious for what turned out to be several minutes. Clearly filmed, that alone was worth jail time. But then Bowden produced a .22 calibre pistol and shot Hudson in the face. Luckily for Hudson, the lightweight bullet deflected from bone and did not kill him.

As the wounded Hudson tried to crawl away, blows raining on him, Bowden grabbed a toughened plastic beer glass and jabbed it repeatedly into his neck but it did not break. If it had, Hudson’s throat would have been slashed and he would have bled out as the ballroom erupted into a pitched battle around him.

Hudson apart, two other people suffered bullet wounds and three were stabbed. One of the wounded was a teenage boy, shot in the foot, leaving him with a permanent limp.

As it happened, Hudson was saved by chance. Which, in a dark turn of events, led to a selfless Melbourne family man being killed 14 months later.

Bowden and Forbes were jailed for their attacks on Hudson, who would move to Melbourne to dodge the Finks.

It was there, in June 2007, that Hudson embarked on a murderous rampage in what became tagged as the “CBD shootings”.

After a night spent drinking and taking drugs in a King St strip club, Hudson assaulted a dancer then dragged girlfriend Kara Douglas out of the club by the hair. A block away, two brave men intervened to protect Douglas from her animal of choice.

One was Brendan Keilar, a solicitor and former country footballer. Hudson shot him dead. The second man was Dutch backpacker Paul de Waard, who was shot in the body. Douglas was also wounded, a blow to her stripping career.

Hudson fled but handed himself in to Wallan police two days later. With reasonable luck, he will die in jail after decades of boredom and fear.

The Ballroom Blitz marked Bowden’s cards, too. After doing his prison time, he also ended up in Melbourne – dubbed “Switzerland” in the outlaw clubs. Bowden’s small brain and big drug use led him to stage a crazy home invasion in South Yarra in 2015. He was accompanied by drug-addled “personal trainer to the stars” Aysen Un Lu, whose car was parked outside, complete with personalised plates.

Clearly, Bowden was no mastermind, criminal or otherwise. The fact he was about a metre wide wasn’t the only reason he presented as an easy target when he moved back to Queensland after the Epping drive-by.

Who killed him? No one is saying. But a Brisbane underworld insider said last week that an old bikie had told him: “Nothing’s secret until three people are dead.”

Whoever bought those getaway cars for the Bowden hit might like to think about that.