Few tears set to be shed as Arthur ‘Neddy’ Smith faces his inevitability

Infamous criminal Arthur “Neddy” Smith will soon breathe his last breath and few people will mourn the notorious thug, writes Andrew Rule.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

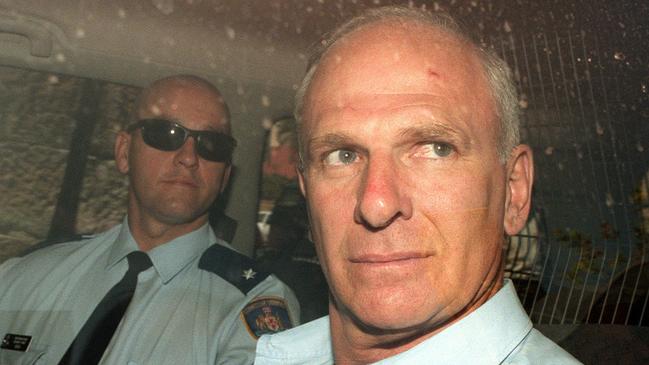

Neddy Smith is alive as this is written, but only just. He has been transferred “home” to Long Bay prison from hospital and could be dead by the time this goes to print. If not this month, then by Christmas.

His timing is excellent. Because Ivan Milat, the monster of Belanglo State Forest, is also dying. And if there is one man in jail who makes Smith look better by comparison, it’s Milat.

When Milat the serial killer takes his last breath, still claiming innocence, the only pity will be that he didn’t suffer cancer for longer. Not that Smith’s exit will be any great loss. Apart from his own family, and barring a few crocodile tears from gangster groupies, most will be glad to see him buried.

As he ends his 75th year, this shaking, shrivelled husk of a man bears little resemblance to the violent heavyweight who cut a dash in the underworld in the 1980s, protected by “the best police force money could buy”.

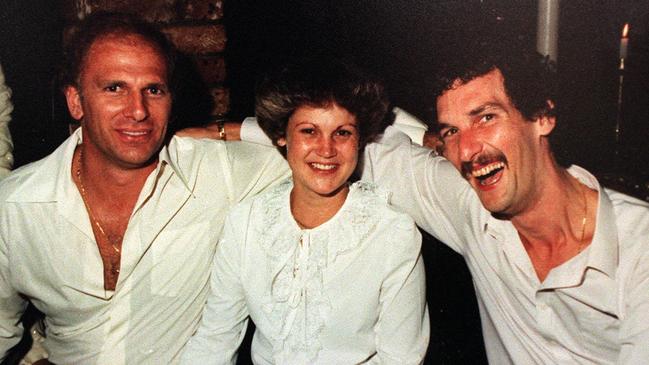

Other crooks were in bed with corrupt cops, but Smith and his “mentor” Roger Rogerson made a pair that will go down in Australian crime history. Mainly because their relationship was captured in all its evil swagger by the television crime drama Blue Murder in 1995.

There’s a scene in Blue Murder as powerful as anything in Australian drama, when the Neddy Smith character trusses a terrified man on a boat and drops him overboard.

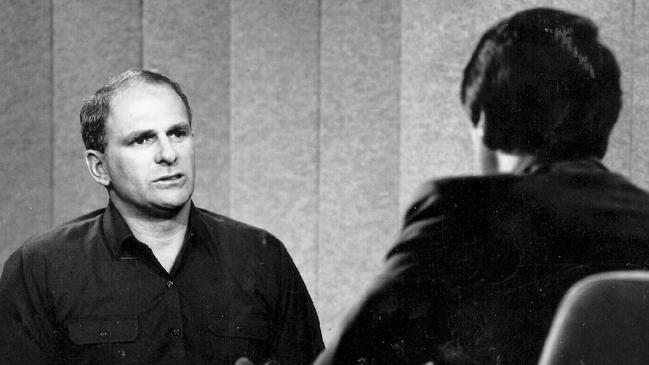

The scene has been viewed thousands of times. Less well-known is its origin: Melbourne crime writer Tom Noble, provoked a chilling admission from Smith when he interviewed him in jail in 1993.

The then young journalist (later Mick Gatto’s biographer) had been recruited to pull together Smith’s memoirs for publication because he had no compromising connections to the Sydney media, police or underworld.

Noble recalls driving to Sydney — a more anonymous arrival than by air — to interview Smith and rewrite a rough manuscript already smuggled out of jail.

When he visited prison to speak to Smith, the first question Noble asked was: “What happened to Brian Alexander?” He was referring to the disappearance of a law clerk who had acted as a go-between for corrupt crooks, cops and lawyers.

Alexander had known where the bodies were buried but not how dangerous such knowledge was until it was too late.

At first, Smith ducked the question. This was understandable as he’d been granted immunity (in return for testifying) for any crimes in New South Wales except murder or breaches of federal drug importation laws.

Noble changed tack, now asking Smith how he “imagined” Alexander had vanished.

Smith’s imagination was much better than his memory. He imagined, he said, that Alexander had drowned after falling overboard from a boat off Sydney Heads.

Why didn’t the body float, asked Noble innocently. Smith instantly retorted that a body doesn’t float when “it’s tied to a gas cooker”.

That one chilling line inspired the scene re-created in Blue Murder and the Underbelly drama Tale of Two Cities. There are echoes of it in the fate of drug-dealing university student Jamie Gao, whose body was found in the water at Cronulla soon after Rogerson and another former policeman were arrested for Goa’s murder in 2014.

Rogerson, portrayed in Blue Murder as using Smith to do his dirty work, has naturally denied any involvement in Alexander’s death.

“Of course Ned did skite that he took him out to sea and did kill a few crooked cops and I’m not sure whether he named me or not but I had a pretty good alibi,’’ Rogerson claimed in 2009. “I don’t like going out to sea in small boats.’’

He would say that, wouldn’t he?

The web of corruption radiating from Rogerson’s crew extended interstate.

The infamous shooting of undercover policeman Michael Drury at his Sydney home in June, 1984, was part of a conspiracy that followed a police undercover operation against a Melbourne crook, Alan Williams, two years earlier.

Rogerson was almost certainly involved in the plot to murder Drury following Drury’s refusal to take a bribe after trapping Williams in a heroin “sting” at the Old Melbourne Motor Inn in early 1982. Williams offered huge money to Rogerson and his crew to make Drury’s evidence go away.

But Drury wouldn’t play by the usual Sydney rules. So he was shot (and almost killed) through his kitchen window — most probably by former Melbourne hitman Christopher Dale “Rentakill” Flannery, whose “employment” was later fatally terminated because he was willing to kill anyone, even his closest associates.

Flannery’s life and presumed death (in 1985) epitomised the “dog-eat-dog” nature of the underworld. With Rogerson, “Rentakill” was dealing with someone as ruthless and cold-blooded as himself. Smith was no better, but was cunning or lucky enough to stay alive in his home patch.

The young Neddy Smith had been a “slum dog” who wanted to be a millionaire. The first time the street kid heard his full legal name, Arthur Stanley Smith, was when he was sent to a boys’ home. He was 11 at the time, locked up for stabbing his half-brother in the hand.

“Neddy” would recall being well-treated at that home but not at the ones that followed as he bashed and robbed his way into a long criminal record. A string of brutal institutions turned the tearaway from Redfern’s backstreets into a violent young thug.

At 16 he was living with a 26-year-old prostitute in King’s Cross and his fate was sealed: street fighter, pimp and standover man on the way to being an armed robber, drug dealer and killer.

He was probably destined for an early grave but got the “green light” from the Rogerson clique that franchised crime in Sydney and had connections in every state. If he paid bribes, he could do anything except hurt a police officer.

Looking back on his life from his prison cell years later, Smith summed up the Australian crime scene in two paragraphs at the beginning of the handwritten manuscript he’d dubbed Thank Christ For Corruption.

“In Victoria there isn’t much corruption. They kill you down there. They certainly don’t do much business.

“Queensland’s not bad for gambling and prostitution but they don’t let you do armed robberies. But when I was working in New South Wales, just about everyone was corrupt and anything was possible.”

This was Smith’s world of bent cops, protected crooks and the people they preyed on. There were many victims but one that stands out is the beautiful and intelligent prostitute Sallie-Anne Huckstepp, one-time girlfriend of drug dealer Warren Lanfranchi, who was shot dead by Rogerson in 1981 at a meeting arranged by Smith.

If Lanfranchi was carrying a $10,000 bribe to give Rogerson, as Huckstepp claimed, it vanished. Smith testified that Rogerson shot Lanfranchi in self-defence. Rogerson stared down the murder accusations and got a valour medal. But the articulate Huckstepp mounted a media crusade until 1986, when she was found dead in a pond in Centennial Park.

Smith, accused of eight murders in his time and convicted of two, later told another prisoner he had strangled Huckstepp then put her in the pond and stood on her chest. He later denied this.

If he did it for Rogerson, it didn’t win him any gratitude. I once asked Rogerson about Smith and he snarled, “Neddy’s a rat”.

As good an epitaph as any for a man set to leave jail in a hearse.