Andrew Rule: Who killed Colonel John Norman Duncan? A swinging sixties murder mystery

It was a society crime replete with affairs, scandal and a trail of blood. Andrew Rule examines a killing that shocked a state.

As an army colonel, John Norman Duncan had survived the Tobruk siege in World War II but there was a bullet with his name on it waiting for him in peacetime. Three, in fact.

As murders go, Duncan’s violent end in 1966 was a classic. The action seemed straight from the hugely popular black-and-white television crime series, Homicide, in which detectives wore hats and stony faces and barked at people on bakelite phones.

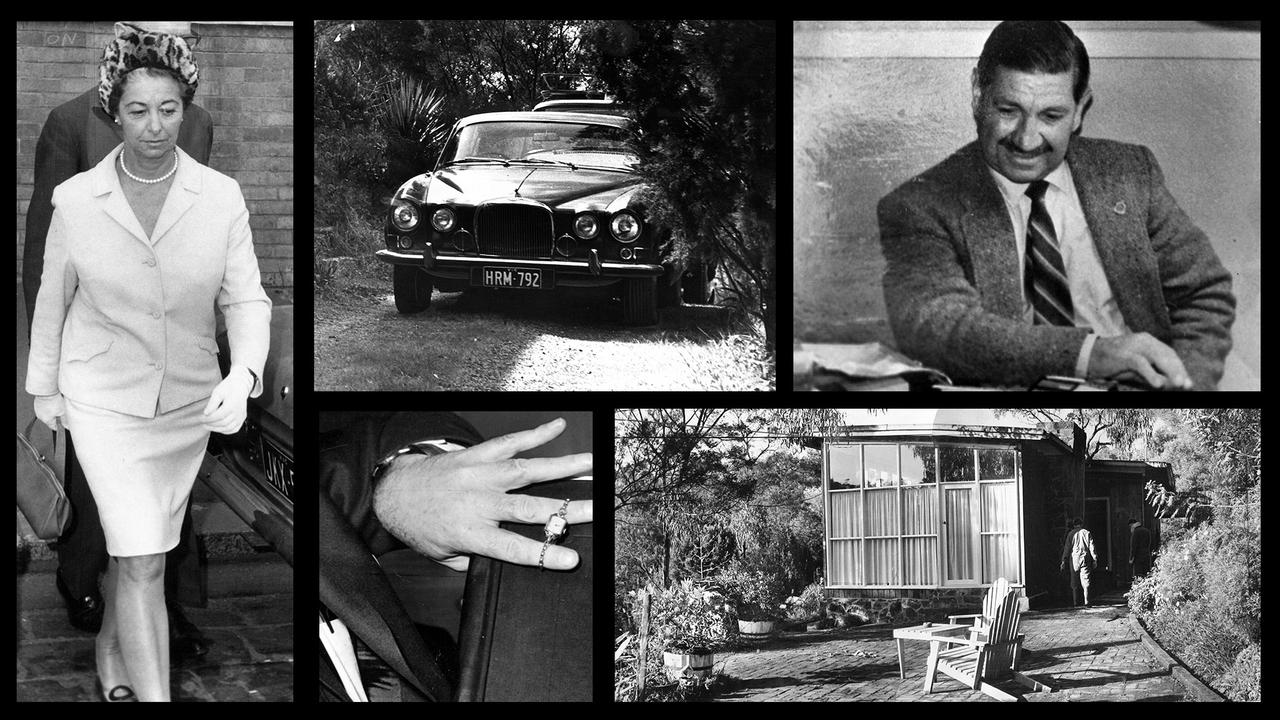

The Duncan murder mystery unfolded in a bayside enclave where rich people drove Jaguars and MGs, drank gin-and-tonic and played around with yachts, tennis and other people’s wives.

This village of privilege was Mt Eliza, where some cheeky local 1960s kids would later form the 1970s band Australian Crawl and write a sardonic song called Beautiful People about trendsetters with homes where “the garden’s full of furniture, the house is full of plants.”

The setting has a whiff of Midsomer Murders by the beach but the blood and bullets were real.

By the time an unknown shooter put two bullets in his head and one in his shoulder, Duncan was a wealthy man: a heavyweight company director who owned several properties apart from his sharp house among trees on a big block just off Old Mornington Rd.

The property was named Glenburn. Its driveway led off a back road, officially Harleston Rd but dubbed “Gin Lane,” a former neighbour recalled this week.

“They were a very fast set there in those days,” she said, adding that she remembered “police coming around to see if we’d lost a spade they’d found near the body.”

Duncan, divorced years earlier, was rumoured to be a “ladies’ man”, a reputation that might have been exaggerated after his death because of the scandal surrounding it.

It happened on September 5, exactly 58 years ago this week. That evening, Duncan’s married lover, Sydna Ferguson, came by his house with a friend to see why he wasn’t answering his telephone.

The former Sydna De Lisle and her aged husband James Ferguson lived in one of the better houses in a district full of very expensive ones.

At 84, the old millionaire was a generation older than his third wife, who’d gone to school at St Catherine’s in Toorak with girls the same age as Ferguson’s older daughters. In fact, Sydna’s society photographer brother Gordon De Lisle had married James Ferguson’s daughter Cynthia, making the old man’s son-in-law his new brother-in-law.

Gossip had it that old Ferguson, whose fortune came from selling his family’s bakehouses in Carlton, knew his bored younger wife was involved with the dashing colonel, who drove hard bargains in business and a gun-metal grey Jaguar sometimes seen parked at quiet spots along the coast.

Apart from his property and business interests (he was a director of Clark Rubber), Duncan was active in the local amateur theatre group, which attracted local women with time on their hands.

He was also known to lend money, like a private bank, a business that could have (wrongly) led thieves to believe he kept lots of cash at home.

Money lending could conceivably have angered someone who was having trouble paying off a loan to the cool and businesslike Duncan but police never identified an aggrieved debtor by going through his accounts.

Apart from liking debts paid on time, Duncan was habitually punctual. So when he had not arrived at the Fergusons’ house for dinner, Sydna Ferguson was worried. He didn’t answer his telephone, so she finally drove to his house with a female friend to check.

There was no sign of life. When she tried the laundry door it would not open. She saw blood seeping from under it and ran back to the car to go for help.

When the police arrived after 9pm they found Duncan’s body lying on his patio. It had clearly been dragged from the laundry, suggesting that the killer or killers had been there when Sydna had come looking.

They found a pillow with holes in it, showing it had been used as a crude “silencer” to muffle the fatal shots, which had come from a .22 calibre weapon.

Police found random possessions piled roughly in one room, amongst them bottles of champagne, Duncan’s shotgun, suitcases and clothing.

The question facing police was whether the intruders had been searching for valuables, such as a safe, when they were disturbed. Or had they wanted the scene to look as if Duncan had fled, taking possessions with him. Or were they “dressing” the scene to look like a robbery rather than a hit?

The interruption by Sydna Ferguson meant the killer or killers never got to finish the job as planned. There was a spade and a pick near the body, suggesting they were going to bury him — if not nearby then after removing him, probably in the boot of his own Jaguar.

Nearly 60 years later, the question remains open. Was it a brutal, stupid armed robbery gone wrong — or a deliberate assassination commissioned by a third party?

Either way, someone did it. A lifetime later, that person has never been charged.

But some retired police suspect he is a sick old man now living out his days on a country property somewhere in the Goulburn Valley — a vast area that begins upriver from Yea and runs north past Shepparton to Yarrawonga.

Unsolved murder files do not get closed — but they do gather dust through lack of information and the relentlessly rising number of fresh crimes banking up.

Sometimes, it seems, an entire generation of investigators passes by without doing more than glancing at some old, cold cases. It’s a fair bet that in the 30 years before 2002, the Duncan file was undisturbed except by silverfish.

Then something happened to attract the attention of a new bunch of homicide detectives. When homicide detective Ron Iddles went to the UK to interview someone on a separate case, he was asked by his cold case colleague Gordon Hynd to go to Scotland to interview a former Frankston resident with a story to tell.

The woman, known as “Elle,” met Iddles in a Glasgow hotel. She seemed friendly and co-operative, and made a statement against her former husband, “Bart”, a serial womaniser and father of her youngest child.

She had her reasons, of course, one being he had savagely assaulted her at their Frankston home after she told him she wanted a divorce so she could go to Scotland with her children, including their then young son.

The late-night assault, apparently with a hammer, did serious damage to her skull and made her bleed profusely. The Supreme Court sentenced him to 12 years with a minimum of nine but the appeal court later cut it to seven years with a minimum of five.

Interestingly, soon afterwards, cold case investigators started checking a tip-off (almost certainly from “Elle”) implicating Bart in the Duncan murder 36 years earlier.

In September 1966, Bart had been 22, and Elle would have been younger, perhaps a teenager. This intrigued police, given that one of few leads uncovered by the old-timers in 1966 was that Duncan had supposedly been seen with young people earlier the day he died.

Also, a witness who knew his Jaguar saw it being driven erratically that day, with lights flashing and one blinker left on, as if he were trying to attract attention, possibly because he was under threat.

In Glasgow in 2002, the middle-aged Elle told the detective she had been with Bart that day in 1966, and recalled seeing the colonel’s Jaguar up a long Mt Eliza driveway as she waited for her boyfriend.

The exact circumstances of her involvement are vague, perhaps deliberately so. But if she were telling a version of the truth, it meant she and Bart had known each other 20 years before they hooked up again in the late 1980s.

After his prison sentence, Bart was last known to be living with yet another woman at his Goulburn Valley hideaway, where he’s rarely seen by locals and unknown to police.

At 80, it’s likely his fighting days are over. But he’s remembered on the Mornington Peninsula as one of the most vicious thugs ever to play suburban football.

A black belt in karate and a fitness fanatic, he not only punched opposition players behind the play but assaulted his own teammates whose home ground was only minutes away from Duncan’s house.

Bart was once banned from football for several years. When he returned, he assaulted a teenage player so badly the boy never played the game again.

Former club mates describe him as a narcissistic sociopath and compulsive womaniser that most avoided apart from a fellow carpenter who worked with him in the building trade.

That man hasn’t seen Bart since visiting him in the remand centre 30 years ago. But he is still loyal.

Asked if he thinks Bart could have shot John Duncan in a robbery, or even in a paid hit, he insists that it wasn’t possible.

Why? Because Bart didn’t have a gun, he says earnestly and without hesitation.

He knows that, the former teammate explains patiently, because when they went shooting together on camping trips, Bart had to borrow guns from his father — who happened to be a keen firearms collector.

It’s not the strongest defence.

Police in 2002 were convinced the answer was that a jealous husband or lover might have organised the murder. But who?

Duncan left his house to Sydna, who sold up and fled interstate with her ailing husband to escape the scandal. But the colonel also left a considerable sum to another local woman, Marjorie Unsworth.

If there were two special friends, were there more?

Everyone concerned is dead now, except an old woman determined to stay in Glasgow and an old man counting down the days somewhere in the Goulburn Valley.