Andrew Rule: The toll of a life spent fighting Victoria’s mad, bad and dangerous

The morning after Chris Glasl and his SOG crew shot a crook, they were losing the adrenaline buzz of the kill — so he racked up a line of cocaine to fill the void.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The morning after Chris Glasl’s crew had shot a man, some of them were losing the adrenaline buzz of the kill, so he and two others racked up a “nice big line” of cocaine to fill the gap.

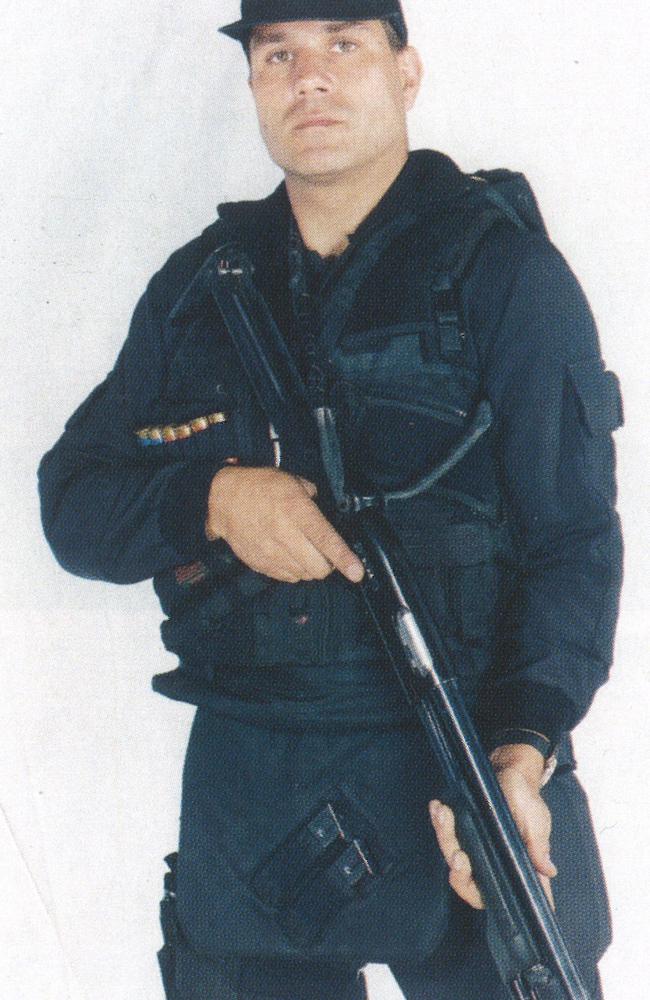

Glasl uses that scene to start the book just published about his four years in the Victoria Police’s Special Operations Group, known as the SOG.

Snorting coke in a police locker room sets the tone for his account of the career that left him with more and bigger problems than he had when he started.

It’s a patchwork of macho “war stories” stitched together with some telling confessions, a haunting memory of a childhood trauma and the beginnings of a road to redemption after years of drug and alcohol addiction.

Whatever its flaws as literature, his book is fearlessly frank. It contains accounts of casually brutal behaviour, potentially fatal mistakes, bad attitudes and the apparent willingness of some to cover up and to hide the truth.

Glasl uses none of that detail as ammunition to criticise the police force or to defend the self-destructive behaviour that derailed his life. He simply tells it as he saw it, scars and all.

Here’s the question: if this is what Glasl thought was okay to publish, what else happened that he did not put on the record?

What are his uncensored thoughts, for example, about Silk-Miller murder suspect Jason Roberts’ steadfast claim that SOG members jammed a gun barrel in his rectum?

(His answer to that is “Of course they would.”)

The SOG command ended up turning its back on Glasl — “for good reason,” he says — but he admires and defends the elite group, underlining that it is absolutely essential to counter violent criminals and the threat of terrorism.

For all that, the book is also a reminder that while there are genuine police heroes, none has so far emerged in the SOG. To be fair, there’s a reason for that: the so-called “Sons of God” don’t need individual heroics to do their job, which is to stop the bad, mad and dangerous with the promise of deadly force.

Rarely did the men-in-black confront anything or anybody that offered them much trouble, and the same applies today. Except the famous black kit is now khaki.

In a country in which some ordinary cops manage to taser or handcuff geriatrics on walking frames, it’s not surprising that de facto commandos are on call to handle anything risky.

SOG members are welded into a (mostly) efficient team by constant training. They are equipped as lavishly as real special forces who go to real wars. The nearest to that for the SOG was crossing Bass Strait in 1996 to help with the Port Arthur massacre.

It’s no surprise Port Arthur gets a run in the book, which is titled “Special Operations Group: The inside story of the most feared and fearsome unit in Australian policing.” Not that revisiting that terrible event through Glasl’s eyes throws any new light on it.

The Port Arthur chapter follows a cheerful aside on how the SOG helped the Blue Heelers television cast and crew film an episode of the long-running police serial.

It’s that sort of book, which began as a private journal he wrote as therapy more than as a comprehensive memoir.

When he joined the force at 19, his aim was to crack the SOG. It took him 10 years. After that high point, Glasl started to crumble.

The thumbnail version of his early life is that he was second of two sons of a German migrant couple in the outer suburbs. Bullied at junior school, he learned to fight back. He became a good footballer and an excellent runner who joined the police on the rebound after being sent back to Montmorency Football Club from Collingwood Under-19s.

Not playing VFL football was a turning point. He decided if he couldn’t be Carl Ditterich, he wanted to be Clint Eastwood.

The friendly young cop became a party animal, smoking a lot of cannabis. But as a natural athlete who trained hard, he survived the notoriously gruelling SOG selection process in 1994. He was in the group until 1998, when he was sent back to uniform at St Kilda “for a spell” and never returned. For good reason, he says.

By then, Glasl was a regular drug user turning into a heavy drinker, someone who knew his way around both sides of the law. He would last another two years in “the job” then drift into an alcoholic haze from which he is still recovering a day at a time.

In print, he comes across as almost cocky about dodgy doings as a street cop, such as ”knocking off” houses known to contain cannabis to ensure he and his (fellow police) mates had a stock of free “choof” to smoke. In person, for a big and once dangerous man, he is gentle and self-effacing.

The fact he worked at the once notorious St Kilda police station boosts the perception of a streetwise, reckless young man, skating on thin ice in a permissive era. And eventually falling through it.

Among his gung-ho “war stories” and descriptions of highly-lethal shotguns, sniper rifles, machine guns, pistols and body armour, there are glimpses of real insight.

One revelation is that since he was 13, he has been haunted by a fire that killed his brother’s best friend in a log cabin on a property the Glasl family owned.

For years, he nursed sorrow and guilt because he believed if he’d been in the cabin that night, the fire wouldn’t have happened.

His book raises an elusive truth, rarely discussed by those we license to hunt humans: that is the addictive adrenaline charge that comes from taking a life in a dangerous confrontation.

People avoid talking about the primitive thrill of surviving by killing but it’s there, the dark impulse that clearly propels certain special forces soldiers to notch up a tally of scalps.

A version of that impulse for years led some former SOG members to hold an annual gathering to drink bottles of Houghton white burgundy to mark the shooting of Walsh St murder suspect Jedd Houghton in 1988. Arguably an example of bad taste in both wine and manners.

Raiding Houghton’s caravan that day knowing he was armed and probably waiting would test anyone’s nerve. In truth, the odds were well in the SOG’s favour, which is fair enough.

The “soggies” are, after all, public servants highly trained and equipped so they have the optimum chance of staying alive — a better chance than traffic cops in their own force, it seems.

In Australia, compared with many countries, policing is overwhelmingly safe, at least physically. Mentally, it takes a toll. Glasl is one of many hundreds of damaged former first responders wrestling invisible injuries.

Fewer than 200 Australian police have died in the line of duty since the bushranger era. More than half of those were killed in road crashes. So few Australian police are murdered that we know the handful of cases since the Kelly Gang ambushed three officers at Stringybark Creek in 1878.

By contrast, about 900 jockeys have been killed in Australia in the same period, more deaths than the total of 862 Australians killed in the Korean and Vietnam wars.

No one wants to say it, least of all those who are publishing Glasl’s book, but he had far more chance of being killed riding his 900cc Honda Fireblade motorbike at high speed off duty than he did waiting around in heavy body armour at sieges or drug busts, armed with up to three deadly firearms, capsicum spray and enough ammunition for a small war.

The two Victorian police who have met sudden deaths since the SOG was founded in 1977 were not shot, stabbed, bombed or killed in high-speed chases.

Paul Carr, head of the SOG, died of a heart attack in 2003 on a Tibetan mountain while practising to climb Everest.

The other died in controversial and oddly cloudy circumstances when he was continually dunked in a pool at the police academy during the deliberately torturous SOG selection test.

His name was Ted Hubbard.

It took a cautious coroner five years to make a finding that obliquely blamed Hubbard himself. This angered his family because the instructors responsible had not given evidence on grounds it could incriminate them.

Hubbard was a respected officer with a black belt in karate and half a lifetime as a competitive lifesaver. But because he hadn’t “ticked the box” to indicate he’d previously had asthma, it left a loophole the system could wriggle through.

For public relations reasons, both Carr and Hubbard were given heroically large funerals, with massed police lining the route leading to the chapel at the academy.

With all the pomp, such funerals could have been mistaken for the farewell of actual heroes. They weren’t.

Paul Carr and Ted Hubbard were excellent employees, personally popular and loved by family and friends. In that sense, like a million others.

A humble young constable named Michael Pratt was, by contrast, a 24-carat hero.

On the morning of June 4, 1976, Pratt was driving past the ANZ bank in Queens Pde in Clifton Hill when he saw three armed men entering the bank.

Pratt, off duty and unarmed, drove his car onto the footpath to block the bank entrance and picked up a jack handle he had in the car. He grabbed one of the robbers and wouldn’t let him go, even when menaced with a gun. Which was why one robber shot him, crippling him for life. He was just 21.

That’s a hero. That’s why he got the George Medal, civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross.

Chris Glasl is no hero but he is a casualty, trying to heal.

“I’m a work in progress,” he says.