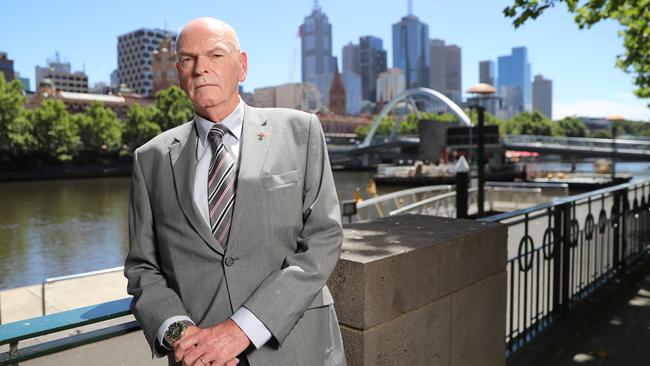

Andrew Rule: Rowland Legg dedicated life to catching killers

It takes a certain sort of person to catch killers — to remain professionally detached yet never forget the horror of the crime. Rowland Legg never wanted to do anything else, writes Andrew Rule.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When Rowland Legg was a teenager growing up in the eastern suburbs, his parents might well have hoped he would choose a respectable profession such as architect or lawyer.

He was well-educated and well-spoken, quietly confident and had an inquiring mind. But he had his own ideas of working in the Law — and it wasn’t to represent those who had broken it. It was to catch them.

By the time he was tall enough to meet the minimum height, young Legg was set on being a policeman: specifically, a detective who caught killers.

Whether this was because, when Legg was at an impressionable age, the family dentist killed his (the dentist’s) entire family, he does not know. Then there’s the fact that a favourite neighbour was the longtime State Coroner, Harry Pascoe, whose barbecues often featured homicide detectives.

Whatever the reason, Legg never really wanted to be anything but a homicide investigator, although there were detours along the way.

His superiors sent him to Canberra for a couple of years to liaise with security organisations against terrorist threats. And he worked in general policing in Melbourne’s busiest inner-suburban stations to get necessary promotion.

Legg first went to homicide in 1979, just six years after joining the force. He stayed three years and knew he would be back.

His second and most memorable stint began in 1994 and continued literally to the bitter end: he was one of a small group of elite investigators who retired early rather than transfer from the squad under a clumsy rotation policy that enforced mandatory moves despite it trashing decades of specialist expertise.

Legg’s name is familiar to Victorians because he was one of those few who were the public face of homicide investigations in this state in the 1990s and into the new century.

This well-known group of senior sergeants also included Charlie Bezzina, Lucio Rovis, Jeff Maher and Ron Iddles — all regulars at crime scenes and on good terms with the media.

Over time, these specialist investigators broadened and refined their skills. They had to be part-counsellor and part-defence lawyer, supporting victims’ families while at the same time staying alert to the fact most victims are closely connected to their killers.

As one observer wrote of the group, homicide detectives “must look at a body like a coroner, and a murder scene with the unblinking eyes of a forensic scientist”. It takes a certain sort of person to stay professionally detached yet never forget the horror of the crime.

Legg worked many high-profile cases. In 1997 he was away from home for months while he investigated the disappearance of toddler Jaidyn Leskie at Moe and then the Bega schoolgirls double murder in the state’s far east.

He worked on the Elisabeth Membrey case, in which the 22-year-old student vanished after finishing her part-time shift at the Manhattan Hotel in Ringwood in December, 1994. Traces of her blood were found in her flat but her body never has been. It is overwhelmingly likely police have spoken to her killer often and at length.

Legg spent weeks around Myrtleford in the northeast, eliminating people from the murder of a little boy, Daniel Thomas, who went missing in October, 2003. The child’s remains were eventually found under the house from which he vanished after being harmed for months.

But when the Herald Sun approached Legg this month to contribute a series of stories about cases he has worked on, he steered away from the well-known ones.

Everything that can be said about those has been said before, he says. In cases such as the tragedies of Jaidyn Leskie, Elisabeth Membrey and Daniel Thomas, still officially unsolved, he and others have definite ideas about who is responsible. But those expert opinions cannot be aired publicly while the prime suspects walk free.

Legg has gone through his diaries and notes for details of cases that few outside “the job” have heard of but that he will never forget.

One of them is not a homicide at all. It is the bittersweet story that surfaced after walkers stumbled over a skeleton in sandy scrub near the Sorrento cemetery in early 2001.

A search revealed glasses, stockings, medicine bottles and a makeup compact and a purse containing coins, the most recent of which were minted in the mid-1950s. A metal detector was used to find a watch and a ring with a 1933 date inscribed on it, all covered with sandy soil.

What happened next is what touches even a seasoned investigator. Missing Persons records threw up the name of a woman who had left her suburban home and vanished in early 1958, exactly 43 years before.

Police were able to identify the remains as those of the missing woman and then to establish that she had almost certainly committed suicide. The puzzling fact that the skeleton was largely buried was explained by prevailing winds blowing sand over it for so long.

The police’s final task was to trace the woman’s daughters and tell them their long wait was over.

They had last seen her the morning she had walked out of the family house when they were teenagers.

One of the daughters still lived in Melbourne. Police met her and handed over her mother’s ring and watch. She burst into tears of relief and pent-up grief.

They could bury their mother at last.

Just occasionally, Legg says, the squad’s grim work produces such “brighter and rewarding days”.

Finding the bodies of the missing eases part of the hell that loved ones go through. Then there’s the deep satisfaction of arresting and convicting the guilty.

It can take months or even years of work to assemble a tight case against an offender. Even then, it doesn’t always convince a jury.

The Leskie case, for instance, led to the arrest of the man the police considered the only viable suspect from the beginning, the “babysitter” Greg Domaszewicz, who told the missing toddler’s mother a farrago of lies on the night.

Domaszewicz was acquitted, brilliantly represented by Colin Lovitt QC.

After Domaszewicz walked, all investigation into Jaidyn Leskie’s death finished. They had given it their best shot and missed, through no fault of theirs.

But it rarely ended that way. For every Leskie or Elisabeth Membrey, the homicide squad nailed dozens of killers. Every one of them with a story attached.

Rowland Legg will reveal some of his personal favourites in print and at heraldsun.com.au in coming weeks. He talks about it in this week’s Life And Crimes podcast. And about the day at Melbourne airport when a murderer he’d locked up years before turned around and recognised him. Awkward, that.

If you, or anyone you know, is struggling with mental health, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

MORE ANDREW RULE

DEBS’ EVIL ON DISPLAY AFTER SILK MILLER CONVICTION

HOW RETIRED AFL COACH BECAME HORSE RACING FAIRYTALE

NEW PODCAST SERIES

Rowland Legg revisits some of Victoria’s most extraordinary crimes in an explosive podcast series.

Listen to a new episode of Fighting the Ultimate Crime every Wednesday, as Andrew Rule sits down with one of the state’s most experienced murder investigators to recount the gripping crimes that shocked the state, and Australia.