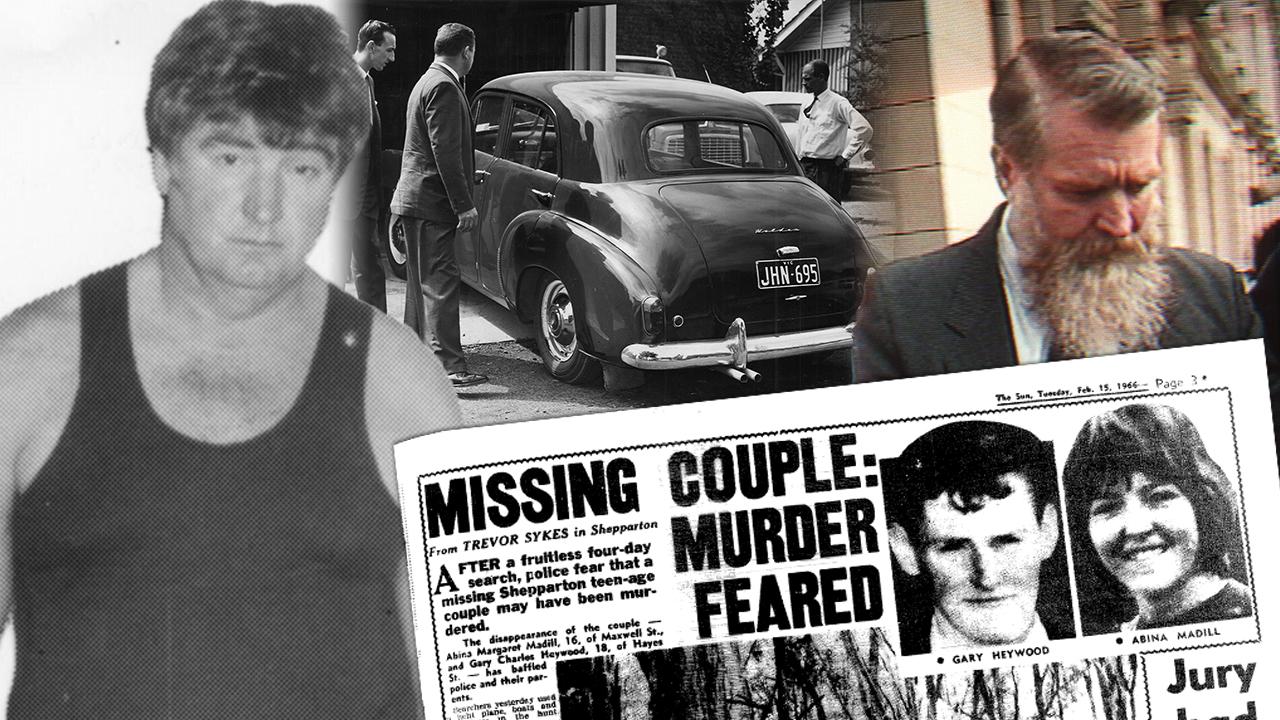

Andrew Rule: ‘Mad scientist’ Rory Jack Thompson flushed wife’s dismembered body down toilet

Rory Jack Thompson, a MIT graduate who worked for the CSIRO, hacked his wife’s body into 91 pieces and flushed them down the toilet in one of the nation’s most gruesome crimes.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For a natural-born genius, Rory Jack Thompson made some bad mistakes. Cutting his wife into 91 pieces and flushing 83 of them down the toilet of her Hobart house was the worst.

When Mrs Thompson’s right middle finger turned up days later in a sewage pump, you might say it pointed squarely at her husband. The brilliant but strange American marine scientist had been hired by the CSIRO to work in Tasmania just months earlier.

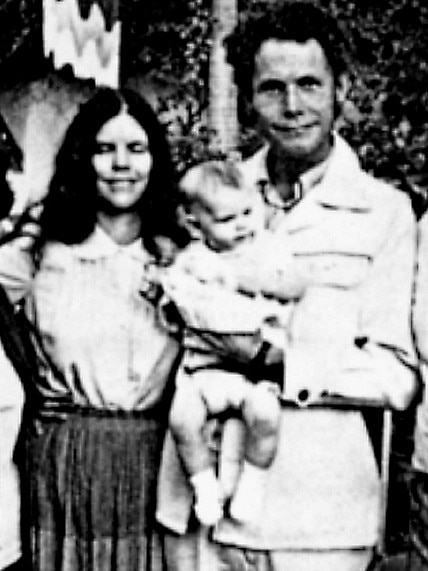

Maureen Ellen Thompson, 37, had gone missing from her rented house at 99 Hill St, West Hobart, on the second weekend of September, 1983.

To no one’s surprise, the fingerprints that forensic officers lifted at the house matched the found finger, which meant they were looking for body parts, not a runaway.

The police called in the plumbers and the full horror story unfolded as the drains were unblocked, piece by grisly piece.

The self-described “mad scientist” who’d committed the crime admitted later in a hushed courtroom, “I don’t recommend murdering people — it doesn’t seem to work very well.”

It is exactly 40 years since Rory Jack Thompson dreamt up divorce by dismemberment. He spent weeks thinking of ways to make his wife “vanish” before going through with his bloody plan on September 10, 1983.

Later, he would calmly confess he had pondered various scenarios like causing her car to crash, carbon monoxide poisoning or pushing her off the Tasman Bridge.

As August ended, a Family Court hearing over the couple’s separation and custody of their two children turned Dr Thompson’s crazed thoughts into premeditated evil action.

He bought half a sheep carcass to practise hacking flesh and bone. On Saturday night, September 10, he had the children, Melody and Rafi, at his house in New Town Rd. After tucking them into bed, he put on mascara, a wig, a dress and a scarf over his overalls and headed to Hill St.

In a bag he carried a meat cleaver, two hacksaws and blades, a chair leg, gloves, a plunger and a piece of rope to use as a garrotte.

He climbed the back fence, waited for the lights to go out, then let himself into the house with a spare key. Maureen was in bed. She fought him but he overpowered her, hitting her with the chair leg then strangling her with the garrotte.

What happened next, over several hours, hardly bears description. It was only after flushing 81 parts of Maureen’s body in the lavatory that he realised he could not actually dispose of the torso that way. He dumped those in nearby bush, cleaned the crime scene and went home to bed.

Next morning, Sunday, he took the children swimming and on Monday he went to work. It was obvious by then that the children’s mother was missing, so he reported her absence to the police.

Even before they had proof of foul play, the police were suspicious of the weird scientist with the arrogant streak.

Maureen’s car was found near her house with the ignition keys and her handbag in it, which suggested she hadn’t left of her own accord. Even if she’d left the car voluntarily, she would probably have taken her handbag or the things in it.

Like most “amateur” murderers, Thompson had focused on the killing, not the huge problem of body disposal.

Like a panicky child who’d broken something, he admitted later, he could think of nothing better than flushing the pieces away.

Strangely, he couldn’t really understand what all the horror was about. It’s not as if Maureen could feel anything, he explained patiently, because she was dead when he cut her up.

This was literally true — but so emotionally unhinged that his lawyer could easily argue that Thompson was legally insane when he butchered his wife and so shouldn’t formally be found guilty of murder. Just locked away.

One of several bizarre footnotes to a macabre story was his lawyer’s name. It was Pierre Slicer.

THE baby that would be named Rory Jack Thompson was born in Seattle in May, 1942.

Elsewhere in America that week, another woman also gave birth to a future genius. His name: Theodore John Kaczynski, later shortened to Ted.

The young Ted, like the gifted Rory Jack, was a child prodigy in mathematics. He was admitted to Harvard as a teenager to begin a brilliant career. But he turned his back on success in 1969 to live a hermit life in a cabin in remote Montana mountains.

There, Ted wrote long treatises about technology’s threat to humanity. To draw attention to his prophecies he made and sent 16 time-delay bombs that terrorised American airlines and universities for 17 years.

Ted Kaczynski was, of course, the anonymous domestic terrorist dubbed “the Unabomber”. That was until his brother and sister-in-law recognised the style of the manifesto the bomber had sent to the authorities, who published it in the hope someone would know who wrote it.

Kaczynski’s family suspected his personality was warped as a toddler by being separated from them when hospitalised for a serious illness.

The parents were allowed to visit the child only two hours a week and his mother always believed that her formerly bubbly and affectionate boy was permanently scarred by the trauma of separation at a vulnerable age.

So what warped Rory Jack Thompson, or was he born that way? The answer to that is locked in the decade between his birth in Seattle and starting high school in California, where he grew up the oldest of three sons in a fractured family.

Rory was a difficult child at primary school because, as a budding genius, he didn’t fit in. Frustrated, he became the odd one out and didn’t find his way until senior school years, when his intellect won attention.

By then, his parents had split. His mother became an alcoholic; his father raised the three boys as best he could.

Rory Jack took up folk dancing while studying at San Diego State College. That’s how he met his first wife, Luella, who was several years older. He married her at 17.

Like the future Unabomber, Thompson graduated young with a mathematics degree. He got into the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology to do a postgraduate degree in oceanography. The couple divorced and Luella retained custody of their daughter. (She didn’t know for 20 years that Rory had fantasised about killing her, something he told Tasmanian police after his arrest.)

Thompson worked frantically. In his career he contributed to more than 40 scientific works, on subjects ranging from mathematics to oceanography. His brilliance overshadowed deep personality flaws. He won jobs overseas, first in Perth, then Norway, finally with the CSIRO in Hobart.

He married his second wife, Maureen, in the United States before taking a lecturing job at the University of Western Australia that allowed them to migrate in the 1970s.

By the time they arrived in Hobart with two children in early 1983, Thompson had a top job as a research scientist but the marriage was in tatters. Maureen filed for divorce on grounds of serious domestic violence. She retained custody of the children but Thompson could have them visit on Saturdays, which gave him the chance to execute his crazy plan.

In court, Thompson disputed a psychological assessment that he had two distinct personalities. He conceded only that he was not always well behaved.

The jury sided with the shrinks. Jurors took only a few hours to find Thompson not guilty on grounds of insanity, which meant he was not officially convicted but put in Risdon Prison hospital as a long-term “patient”.

Thompson became a “trusty”, doing jobs around the prison in ways that most criminals would not. As a prison gardener, he was let outside the gates to tend plants.

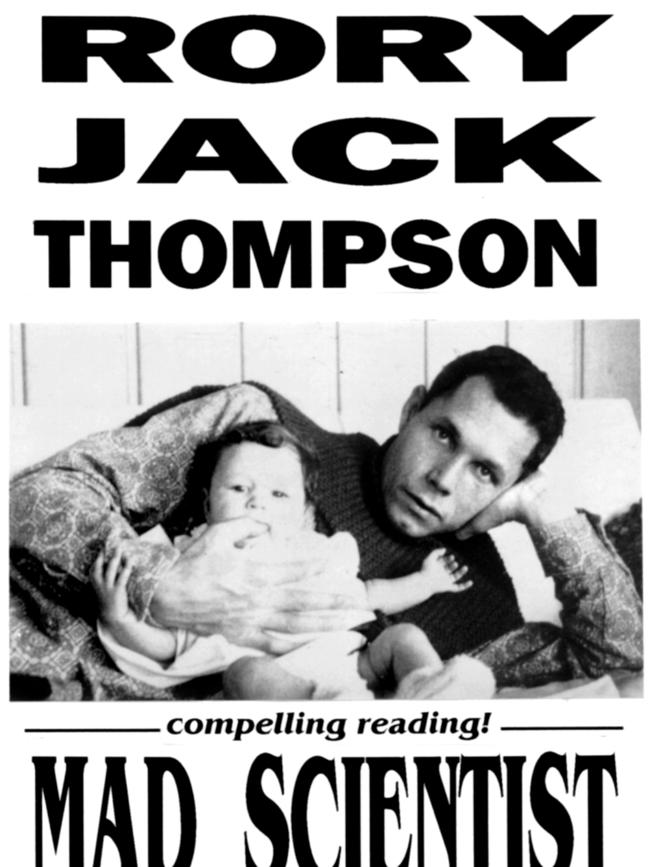

He wrote a rambling biography, titled Mad Scientist, issued in 1993 by a local publisher. The same publisher also negotiated with foreign investors for rights to a 3D device for viewing TV and computer screens that Thompson invented and patented from prison.

But he was working on another plan, too. He organised a bank card linked to an account with funds in it. By this time he had officially changed his name to Jack Newman.

On July 5, 1999, he walked away from the garden outside the prison to a nearby bus stop. If he hadn’t started chatting to a woman waiting for the bus, it could have been one of the great escape stories.

Noticing his prison cap and clothes, the woman made up an excuse then rushed home and called the police, which meant they were looking for “Jack Newman” by the time he got to Hobart Airport shortly afterwards, having taken $490 out of an ATM.

He bought a ticket to Melbourne and boarded an Ansett flight after passing through security in prison overalls and beanie. The police arrived before the jet took off. A little later and he would have been gone.

Back at Risdon, the infamous “patient” lost all privileges and plunged into deep depression. On September 18 that year, he hanged himself, using his shoelaces. His death was one of five that led to an inquiry into slack prison procedures.

It would take almost three years for the Australian legal system to catch up with the escape attempt that had so nearly come off.

In 2002, Tasmania’s shadow Attorney-General Michael Hodgman revealed in parliament that if Thompson had flown to Melbourne, Tasmania had no power to bring him back because he was not a convicted prisoner and therefore could not be extradited.

Hodgman, a criminal lawyer by trade, revealed that another fugitive had already pulled off an international escape using the same loophole: a violent “patient” had fled a Queensland jail to Victoria then to Italy via New Zealand.

Rory Jack Thompson might have been mad but his last plan wasn’t crazy at all. He was only minutes away from pulling off a brilliantly simple escape.