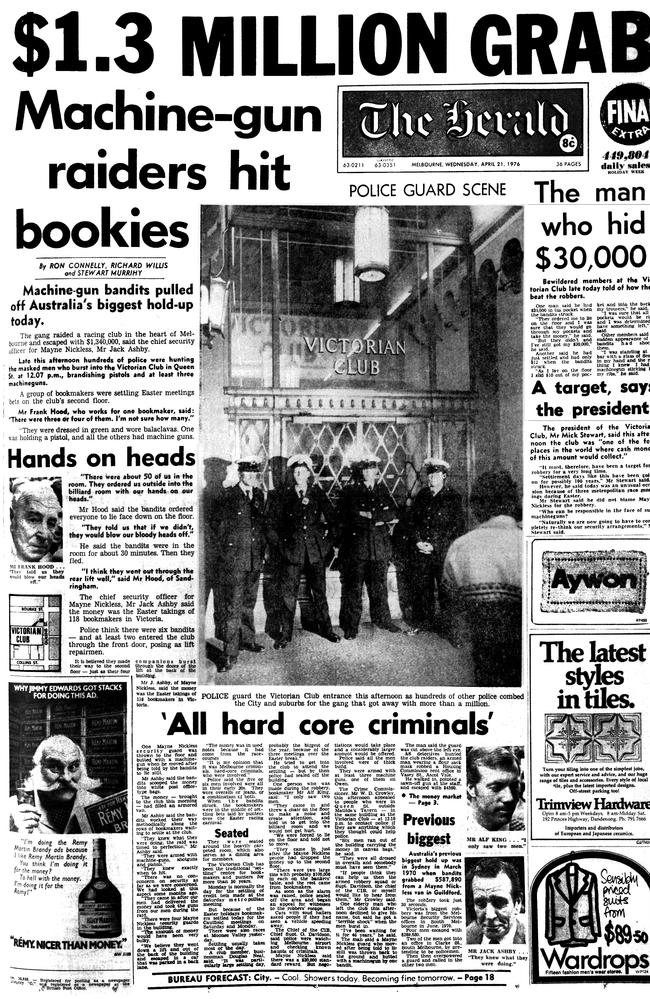

Andrew Rule: How ‘smartest crook in Australia’ kept Great Bookie Robbery role under wraps

Stan James was never convicted of a serious crime in a long and seemingly law-abiding life — but after his burial last week, his role as a criminal mastermind can finally be revealed.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Stan James was the cleverest crook the public never heard of, known only to the few who were told of his secret role in the Great Bookie Robbery.

But it is only since James was buried last week that his role as a criminal mastermind can finally be revealed.

At 78, the longtime Essendon resident was a virtual “cleanskin”, never convicted of a serious crime and barely charged with anything in a long and seemingly law-abiding life.

His only public link with the Great Bookie Robbery of 1976 was that his wife was charged soon after the robbery with conspiracy to handle part of the multi-million dollar heist.

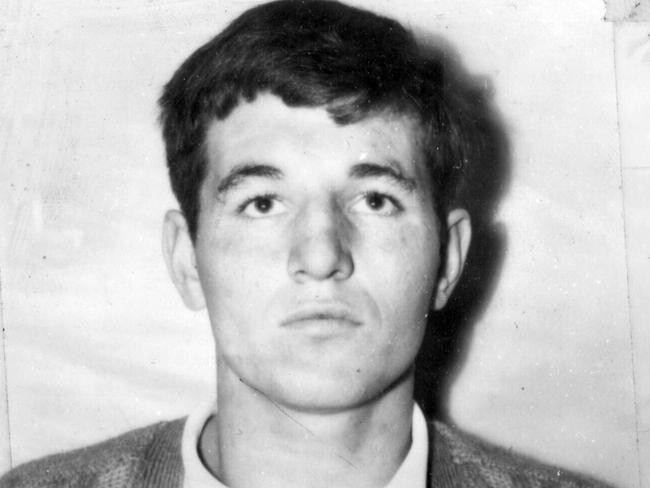

But Lorraine James was cleared of the conspiracy charges, along with the wife of notorious armed robber Normie Lee — the only man charged over the huge robbery at the Victorian Club in Queen St in April, 1976.

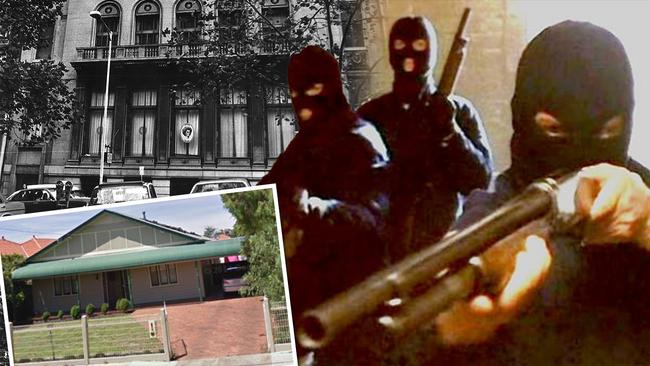

Lee was also cleared for lack of evidence but well-informed detectives believed what the underworld knew — Lee was one of a well-drilled crew led by dashing armed robber Raymond Patrick Bennett (AKA Ray Chuck) following a plan that Stan James helped draw up.

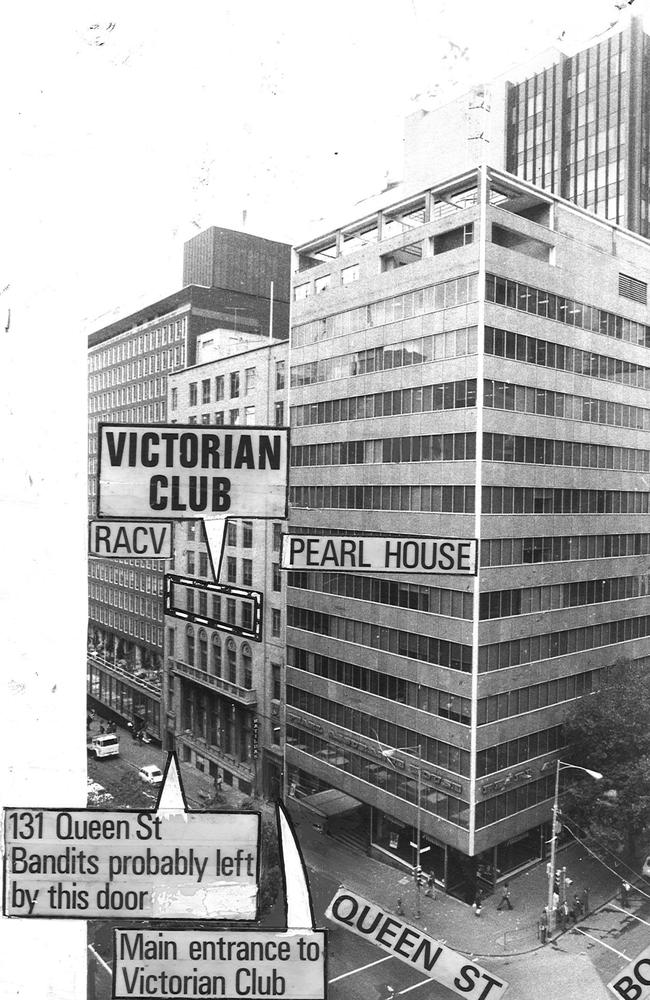

Police heard whispers that James was recruited by Bennett’s longtime associate Russell Cox to monitor the Victorian Club over several weeks and map a detailed plan.

James and his wife bought a house in Essendon soon after the robbery, which was staged on the Wednesday after Easter, the biggest bookmaker settling day of the year.

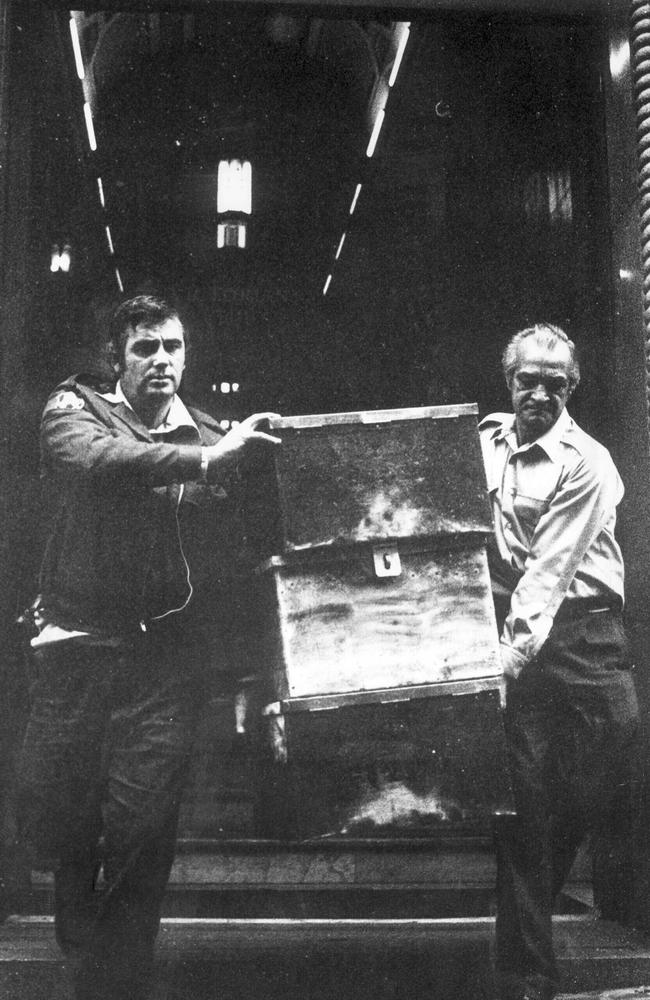

Banks had been closed since the previous Thursday, so the accumulated cash holdings of 116 bookmakers were in strongboxes brought to the club by armoured car from the security company’s North Melbourne depot.

It is believed that the robbers had organised a corrupt senior police officer to divert detectives at the last minute from their usual role of “minding” the cash after it was brought into the club from the armoured car.

Stanley Ernest James, born 1946, was known by a few insiders as a planner of robberies that depended on split-second timing, keen observation and iron discipline.

He masked his secret income by hiding in plain sight, living simply and working for years in low-key jobs such as council maintenance work.

An Ascot Vale publican was tipped off about him by a well-informed drinker who noticed James laying asphalt in a nearby carpark.

Years later, a local football star turned businessman was taking a shortcut down an Essendon street with an armed robbery squad officer who told him: “The smartest crook in Australia lives in this street”.

“Who’s that?” asked the surprised sportsman.

“Stan James,” said the superintendent.

Despite the King St house being bugged by police for long periods from November 1980, it seems no useful information was ever gathered.

It seemed to frustrated detectives that Stan James’s only weakness was golf. For more than 30 years, he was a member of the private Medway Golf Club at Maidstone.

For younger and better golfers, Stan seemed just another old guy who sometimes played better than his handicap suggested.

What fellow golfers didn’t know was that Stan’s best score didn’t happen on a golf course. It was his slice of the Great Bookie Robbery of 1976.

It wasn’t until he died three weeks ago that his intriguing past could be sifted for evidence of his part in the legendary heist that officially netted $1.38 million dollars, but was actually much bigger because of the “black money” bookies got from undeclared credit bets.

Even among the shrinking number of people who know more about the bookie robbery than they told police, Stanley Ernest James is a shadowy figure, as camera shy as his one-time associate Russell “Mad Dog” Cox.

He was low profile, more about “time and motion” than high emotion. Heroics, dramatics and gunplay weren’t his go.

Stan wasn’t one of the six robbers who burst into the Victorian Club in Queen St with guns and masks minutes after midday on April 21, 1976.

He wasn’t the fake refrigeration mechanic who jammed the lift with a chair to stop extra people from entering the second-floor room where 116 bookmakers were gathered to settle millions of dollars from three big Easter race meetings.

But he is prime suspect as the “inside man” who reputedly infiltrated the club in the weeks before the robbery, chatting to staff and members and mapping a precise picture of the lay-out — notably the position of a long-unused door in a side wall that led from the building next door.

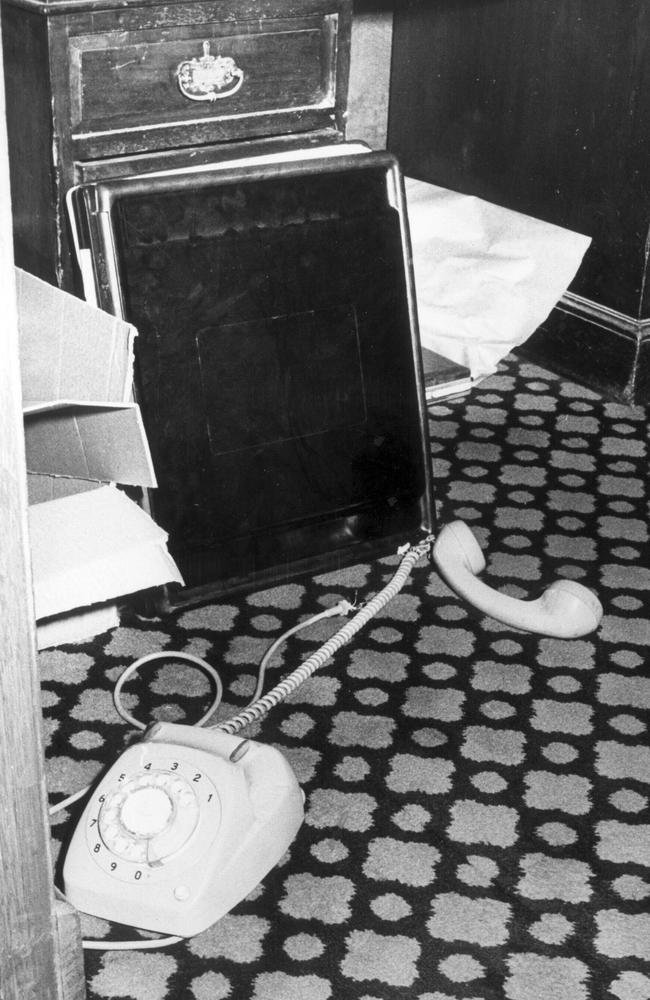

It was through this forgotten door that the robbers entered the cash room. They left 11 minutes later, leaving stunned bookmakers lying face down on the carpet.

Whatever it was Stan James did to help pull the perfect heist, it was enough to make him keep his head down afterwards. He knew he was a target when gang members were hunted by “toecutters,” predators chasing the loot.

James was never charged over the robbery, but he was well and truly in bed with one of few who were. Fact is, he slept with her for decades.

The story goes like this.

Normie Lee was the only one of the gunmen charged over the robbery. Lee, a “good crook” who ran a dim sim factory in Essendon, was charged with robbery at the Victorian Club of $1,387,540, and with receiving $124,000 of the proceeds.

In 1977, a magistrate found not enough evidence to prove either charge, also dismissing conspiracy charges against Lee’s partner Lorraine Hogan and Stan James’s wife Lorraine Mary James.

Lorraine James is now a respectable grieving widow with a fascinating story to tell. The couple were not big talkers, as police discovered after attempting to record what was said in their home.

Stan and Lorraine had bought the old house at 51 King St, Essendon, soon after the bookie robbery. Much later, a former tenant of the house, an alert man named Michael Hinch, told this reporter what he’d found while living there for a year while the James family hid interstate.

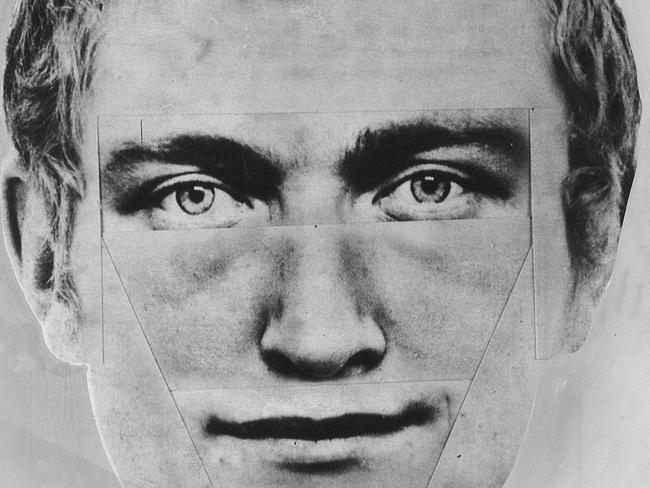

It began in November 1979, days after the audacious shooting of bookie robbery leader Raymond Patrick Bennett (called Ray Chuck by fellow crooks) at the old magistrates court opposite Russell St police station.

Bennett, one of the most dashing crooks of his time, had become a sworn enemy of those loyal to the violent Kane brothers — standover men Brian, Les and Raymond.

Hostility festered into deadly enmity after the bookie robbery. The Victorian Club raid netted somewhere between the lowball official figure of $1.38m and a high end of many times that, given the bookies’ habit of topping up strongboxes with undeclared cash.

At a time when suburban houses sold for less than $50,000, a possible $5m score attracted lethal predators.

The Kane crew headed the queue but there were bent police and “toe cutters” like Linus Patrick Driscoll, who tortured robbers to extract cash from them.

Ray Chuck’s crew became targets and didn’t like it, leading to a pub brawl in which Chuck’s mate Vinnie Mikkelsen bit off part of Brian Kane’s ear.

It’s hard to be a standover man when someone has bitten your ear. The Kanes had to get revenge or lose more face.

Ray Chuck read the play and hit first. In late 1978, three masked men burst into Les Kane’s not-secret-enough hideaway in Wantirna, bundled his wife Judi and their two small children out of sight and shot Les. His body and his Ford Futura vanished forever.

Mikkelsen, Chuck and Laurie Prendergast beat the murder rap for lack of evidence but the Kane camp had a lower standard of proof. They declared war.

Mikkelsen fled outback, stayed for years and survived. His mate Laurie Prendergast was abducted and executed, his body never found.

Chuck, alias Bennett, was shot dead in the old court building, almost certainly by Brian Kane, disguised to look like a lawyer. “Cop this, mother----er!” the shooter snarled as he pulled the trigger.

This brazen hit was executed at court because it was the only chance before the target went to prison on a minor charge; he thought he’d be safer behind bars than on the street.

The hit spooked anyone involved with the bookie robbery. No one more so than the man calling himself “Steven Jameson,” the false name James used to buy the Essendon house.

“Jameson”, who would later quietly change the faked name back to Stanley James on legal documents, was so scared by the Ray Chuck hit that he and his wife headed to NSW within days, handing the house to an agent.

That’s how Michael Hinch, trainee train driver, came to rent the old house just before Christmas, 1979.

Hinch noticed things the investigators had missed.

Police knew James had not been one of the bandits waving guns at the bookies in the Victorian Club. They also knew he was trusted by the hardcore: Ray Chuck, Normie Lee, Ian “Fingers” Carroll, Brian O’Callaghan and a couple more, plus trusted helpers.

The detectives who later charged the two Lorraines (James and Hogan) over holding money from the robbery, had the James family under surveillance well before the “Bennett” hit.

Investigators concluded James was a “time and motion man,” an anonymous face from Sydney with little exposed form recruited to observe the Victorian Club’s routine, escape routes and other details.

Victorian Club president Michael Stewart had noticed a quiet, well-dressed man around the club for weeks before the robbery. The stranger mentioned being from Adelaide. He got to know the club regulars and surrounds. After the robbery, he vanished.

Whether Stan James was the spy is unprovable. But it was soon clear to his tenant, Michael Hinch, that James had worried about police raids — or something more sinister.

There were heavy bars across all windows and a steel-reinforced door protected the wooden front door, all deadlocked and bolted. Inside, iron brackets had been fixed to the wall either side of the doorway so a bar could be dropped across it.

There was more. Hinch noticed that a corner fireplace was offset at an odd angle. When he concreted the shed floor outside, he found empty bullet shells buried there.

Hinch was curious about the offset fireplace. He found a manhole in the bathroom and discovered that the roof joists were decked with boards so he could walk easily under the high gable.

At the front of the house, the gable end had an open trellis, letting an observer hide in the roof and watch people and cars approaching. There were two U-shaped fittings on swivels ideal to use as a rest for a rifle. A shooter could repel many attackers without being seen.

Hinch checked the ceiling around the chimney above the crooked fireplace. He found a trapdoor and a light switch. It revealed a tiny shaft down to a space behind the fireplace.

The hideaway was just enough for one person to sit. In it were two stools and an ashtray of butts. A smoker had obviously hidden there, which explained the air vent in a nearby outside wall.

None of it made sense to the puzzled tenant until the end of 1980, when the agent told him the owner was returning. Two detectives also got the memo: they turned up within days.

The policemen said the house owner was involved with the bookie robbery and had fled after Ray Chuck was shot. They borrowed spare keys and hinted they’d be bugging the house — “Don’t say anything you don’t want us to hear.”

Hinch told them about the buried bullet shells and the roof observation post. When he revealed the secret space behind the chimney, he got quite a reaction.

“The copper says, ‘You’re shitting me!’ He was furious they hadn’t found it when they searched the place before we moved in.”

Days later, Hinch moved out. He never met his landlord, the one he knew only as “Steve Jameson.”

But if he stayed around the same suburbs, it’s likely he saw the mystery man around the streets in the disguise of those who want to be invisible: a high-vis vest.

Stan Jones worked for years on the Moonee Ponds council road gang, patching roads and car parks. He also ran a floor-sanding business. And did a bit of consulting for trusted clients.

When he wasn’t playing golf, he liked to stay busy.