Andrew Rule: Cunning crims prove ‘escape proof’ jail doesn’t exist

Aussie crooks have been escaping from prisons from the moment they started being thrown in them. These are some of the most outlandish jailbreaks and the cunning crims who executed them.

Jailbreaks make good stories, from The Count of Monte Cristo and Papillon to the AC/DC song about “a friend of mine on murder” who made it out with a bullet in his back.

Going over the wall or under it has inspired a whole genre of films.

David McMillan knows a bit about the escaper caper. He pulled the daddy of them all when he checked out of the “Bangkok Hilton”.

McMillan the villain has opened up about his pet subject with Mark Dapin, who is to true crime writing what “McVillain” was to true crime: an often original thinker with a subversive wit.

Dapin hangs around boxing gyms and is a knock-out specialist: he knocks out books the way Mike Tyson KO’d contenders.

His latest book, Prison Break, revisits the better escapes committed by Australian crooks both at home and, in McMillan’s case, abroad.

“The rule is, escape early and escape often,” McMillan tells Dapin.

Trouble was, when the police first came for him back when he was “flying”, young McMillan wasn’t ready.

If he’d had a week’s notice, he quips, life might have turned out differently. Or not.

McMillan and his mate Michael Sullivan, former champion pole vaulter, were smuggling heroin from Bangkok.

The brash youngsters did so well they bought houses in Brighton and Beaumaris, drove Porsches, ate at top restaurants, used the finest drugs.

McMillan’s girlfriend was the beautiful but doomed Clelia Vigano, from a prominent Melbourne restaurant family.

Sullivan’s was Mary Escolar Catilo, a wealthy Colombian architect’s daughter.

McMillan, wickedly intelligent and so careful in other ways, would double park in the city and wander around carrying stacks of cash in a plastic bag.

It all came tumbling down in early 1982.

When the police came for McMillan, they found him in bed with Clelia in his Beaumaris house. Same with Sullivan and Mary in Brighton.

McMillan and Sullivan went to Pentridge to await trial.

Their girlfriends went to Fairlea women’s prison — where both died in a fire lit by a crazed prisoner, who also perished.

Fast forward a year during which McMillan and Sullivan were locked up with intractables and killers in the Jika Jika high security wing, the “human zoo”, despite the fact they were remand prisoners.

When they got back into the mainstream prison, their loyal accountant Max McCready relayed a plan apparently concocted by rogue aristocrat Lord Tony Moynihan in the Philippines.

Bad Lord Tony sent a disgraced British soldier, one Percival Roger Hole, to Australia to do his worst.

Hole was to get a helicopter to land on the prison tennis courts to whisk the escapers to a nearby park. From there, they’d be driven to a waiting makeup artist in Brunswick then to a trucking yard to hide in crates to be carted to Sydney. Or, alternatively, to hide in a boat to be trucked interstate then launched to sail to the Philippines.

That all sounds like the offcuts from a Bond script but what actually happens is more Marx brothers: Hole hires a “counter surveillance” expert who turns out to be an undercover cop.

To prove the escape plan is not just fantasy, police have to show it can be done. So they land a chopper inside Pentridge and three SOG police jump aboard and take off in less than a minute: proof that truth trumps fiction.

McMillan and Sullivan are thrown back in Jika Jika because of the helicopter escape plot. But it is other inmates who show that the “escape proof” zoo is anything but.

A key player in the great Jika Jika break out of 1983 is “Clever Trevor” Jolly, who’d been swiftly recaptured after going over the wall three years earlier.

Jolly’s leatherwork hobby requires leather dye. The fumes are overpowering in the Jika Jika passages and cells.

Following prisoner complaints, and their own comfort, officers agree to let Jolly wheel his leatherwork trolley through a series of locked doors as far as a roller door opening into a recreation yard. The door is raised about thirty centimetres to let the fumes escape.

At night, no officers watch the yards because prisoners are locked inside the unit, effectively controlled by two officers sealed in the “control spine”.

As “Clever Trevor” moves his trolley back and forth the officers get used to (remotely) opening each door in the passage for him.

All that a lazy officer sitting at his post sees is Jolly’s head and shoulders move past the security glass.

Which is exactly what happens. But each time Jolly trundles past, the bottom of his trolley holds a stowaway who then squeezes under the roller door into the empty recreation yard.

After practice runs, four prisoners pull the real thing on July 30, 1983.

The stowaways pad razor wire with blankets to get into the mainstream prison yard with a homemade grappling hook and blanket “rope”.

In four minutes, four dangerous men are on the street and Jika Jika’s reputation is in tatters.

Three fugitives — Tim Neville, David McGauley and David Youlten — are scooped up within weeks. The worst of the escapers, chess playing triple killer Robert Wright, stays on the run until New Year’s Day, 1984.

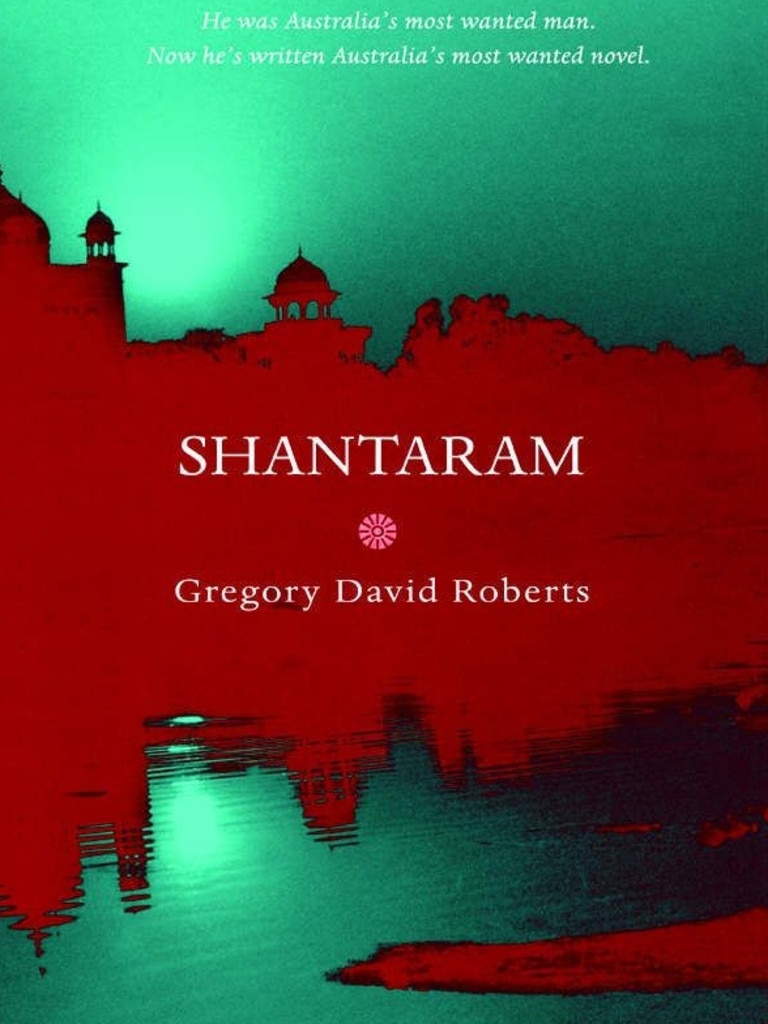

Jolly had escaped three years earlier with another prison intellectual, Greg “Doc” Smith, a charming, manipulative, narcissist who would much later find worldwide fame (as Gregory David Roberts) with the global bestseller Shantaram.

The novel is inspired by his story of fugitive life in India after escaping Pentridge, then Australia.

It is no more far-fetched than the bare facts of its author’s decade on the run.

Smith had been a well-educated student infected with grandiose delusions, 1970s protest politics and a fierce heroin habit.

He had his own ASIO file well before police first heard his name in 1978, when another crook tipped off detectives that he was “good for” a string of armed robberies.

Inside, Smith ponders escape because (he later claims) he feared being killed.

But a former officer has told Dapin that in fact Smith was a “trustie” allowed to move around the prison.

Smith and Jolly did landscaping near where builders were renovating a building. During the builders’ lunch break the pair — wearing overalls over football jumpers — slipped into the empty building.

They used a builder’s power saw to cut a hole in the ceiling then got onto the roof. They used an extension cord to abseil down the outside wall, then shed the overalls and jogged off like footballers on a training run.

Smith was smart enough to split up with Jolly. He took an astute friend’s advice that police would grab them if they stayed together and went near family, friends or criminal contacts.

As Dapin points out, some details in Smith’s stories are inconsistent or exaggerated. There is no proof that he was harboured by a well-known female author, or helped by a university academic, or spirited to Perth with a group of union officials.

In Perth (Smith told me in 2005), he lived with university students, one of whom gave him a passport. He flew to New Zealand, grew marijuana to raise cash then scammed his way to India with false ID.

The fact he was not caught until a decade later, in Germany, shows his story is extraordinary. But it is no more extraordinary than an old favourite: David McMillan’s famous escape from Klong Prem, the notorious “Bangkok Hilton”, on a hot August night in 1996.

McVillain scaled seven walls that night on his way to the airport and freedom. But the best bit was his sauntering away from the prison with an open umbrella. Because escaping prisoners don’t carry umbrellas…

Prison Break has many other escape stories. It hits the stores the first week of August.