Andrew Rule: Bravery of men and horses who lived and died in Palestine desert lives on

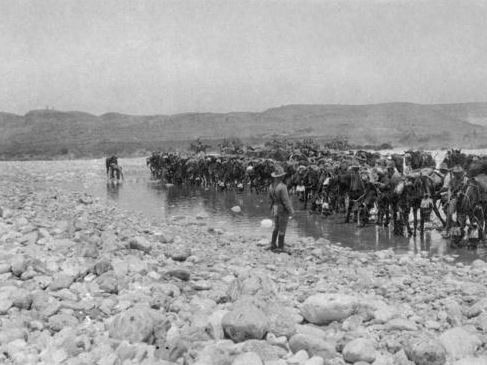

War is not glorious but galloping horses are, which is why the stories of the men and horses who lived and died charging the wells of Beersheba in the Palestine desert endure more than 100 years later.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

War is not glorious but galloping horses are, which is one reason that Australian Light Horsemen charging the wells of Beersheba in 1917 has been commemorated so movingly in film and books.

Two generations after the last light horsemen left us, what they did at Beersheba still moves us. And the stories of the men and horses who lived and died in the Palestine desert live on.

There’s Bill the Bastard, the big rogue horse who saved his rider and four Tasmanian troopers under fire in the Battle of Romani — three on his back and one on each stirrup.

Bill had been feared for bucking off troopers until the master horseman Queenslander Maj. Michael Shanahan managed to stay on him. It was Shanahan who rode Bill the night he carried the four troopers to safety.

Shanahan got the Distinguished Service Order for bravery. The legend goes that Bill the Bastard carried a machine gun in the charge at Beersheba the following year.

Bill was station-bred, big and rough and coarse. Midnight was neat, sleek and beautiful, a jet-black Thoroughbred mare whose owner Guy Haydon had brought with him when he enlisted in the 12th Light Horse Regiment in 1915.

Lieut. Haydon was from a renowned family of Hunter Valley horse breeders that still breeds world-class performance horses, and Midnight was from one of their best bloodlines, one the family still has a century later. She was an equine aristocrat and, with Haydon in the saddle, excelled at everything asked of her.

Haydon and Midnight were a great match and they made a reputation for Australian horses and horsemanship.

Such a superbly-bred mare would never have been sent to war if Guy, a top polo player and all-round sportsman, hadn’t wanted to take her when he signed up in 1915. His family trusted the sure-footed Midnight to keep their “boy” safe.

She was the fastest horse in the district and brilliant on her feet. In a “Desert Olympics” staged between Australians and the British cavalry, Haydon rode her to win a “quarter-mile” sprint, an obstacle race and a formal equitation test.

Midnight had the class to out-gallop most mounts in the charge at Beersheba, and that speed and courage might have cost her life.

As she jumped over a trench at the head of the charge, a terrified Turk shot upwards through her belly. The rifle bullet tore through the mare’s body and the saddle and hit Haydon next to his spine.

As his great-nephew, Peter Haydon, wrote decades later, “The mare had saved his life, absorbing the point-blank shock of the bullet.”

Guy lay wounded all night, bleeding and broken-hearted, next to Midnight’s body. It was October 31 — 12 years to the day since Midnight had been foaled in 1905 at the Haydon home property in 1905.

Guy Haydon recovered to go back to the Hunter Valley and Bill’s rider Shanahan lost a leg but got home to Queensland. The horses were not so lucky. Of the 136,000 Australian “Walers” sent to that war only one horse returned.

The stories of Midnight and Bill the Bastard inspired Melbourne businessman Bill Gibbins to create the Jericho Cup at Warrnambool in 2018 to honour the Light Horsemen and the horses they rode into battle.

Next Sunday is the sixth running of “the Jericho”, which has rapidly become a “Bool” fixture that bookends the Grand Annual Steeplechase in May.

The $300,000 Cup is 4600m, by far the longest flat race in Australasia — a marathon run over the Grand Annual course without the 33 jumps.

The race’s name is a tribute to a “three mile” race that “Banjo” Paterson and his fellow Light Horse officers staged in Palestine in 1918 to fool the enemy into a false sense of security before launching an attack.

Holding a race meeting in the desert, widely promoted so the Turks would hear about it, was a clever way to provide cover for a massed gathering of soldiers and horses.

The ruse worked. So has Bill Gibbins’ idea of commemorating it, which is why thousands of spectators will flock to Warrnambool next weekend to see horses streaming up the hill in the Brierly Paddock behind the course proper, one of the finest sights in sport.

Midnight and Bill the Bastard and the men who rode them are remembered and their stories widely known. But there are more stories about the Light Horse than those. One of them is about a Danish aristocrat killed in the charge at Beersheba.

His name was Eigil de Neergaard and his story has been pieced together by a Danish history buff, Ulla Hadar, who lives in Israel.

A few years ago, Ulla was looking through the neat rows of Australian war graves (at what is now correctly known as Beer Sheva) when she noticed what was clearly a Danish surname on a headstone. It was the grave of Sgt Eigil De Neergaard.

De Neergaards were a well-known aristocratic family in Denmark, where Eigil was born in 1885, second of three sons. His grandparents and great grandparents owned manor houses on big estates and his father managed Lungholm Castle.

The young Eigil did compulsory military service from the age of 18 and worked as a farm manager on the splendid estates of other aristocratic families. As a younger son, he had to make his own way in the world.

In the New Year of 1912, Eigil arrived in Australia and obtained 1745 acres of uncleared scrub in Smoky Bay on the far side of South Australia. A rare photograph taken then shows him in a pith helmet and knee-length riding boots.

He cleared some land to grow wheat but by the following year had left to go to Sydney. He enlisted there in January, 1915, in the 12th Light Horse. At 29, with his Danish military experience, he was made a Corporal.

The Light Horse troops were sent via Egypt to Gallipoli to fight on foot. Only 23 of De Neergaard’s unit returned to Egypt to be reunited with their horses.

The cheerful Dane was popular and capable and soon promoted to sergeant, despite facing a court martial for breaking regulations by sending letters to his family and a young woman in Denmark.

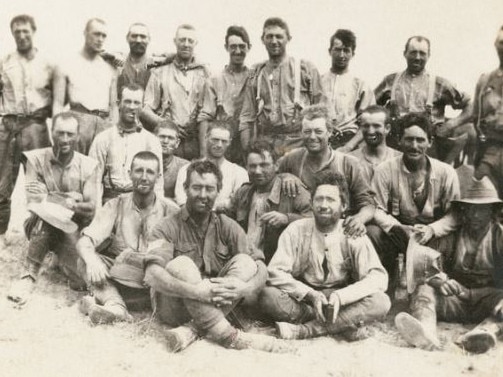

He kept a photograph album, which suggests he’d smuggled a camera into Egypt. One of the photographs is of him with his favourite horse. Another is of him with two other officers — one being his friend Lieut. Guy Haydon, Midnight’s owner.

De Neergaard was shot during the charge at Beersheba. The bullet passed through a pocket book he was carrying. It did not kill him immediately but he died a few hours later.

While Guy Haydon was in hospital recovering from the wound to his back that could easily have killed him, too, he wrote sorrowfully about his Danish friend: “Poor old Neergaard was killed, I was awfully sorry about him, he was such a good Soldier, absolutely fearless.”